Elizabeth Dwomoh reviews an illustrative case on how the reality principle applies when a property has undergone major improvements.

Key point

- When undertaking a comparison of an improved and unimproved house and premises, section 9(1A)(d) required the value of the potential for improvement to be excluded from the valuation of the unimproved house

Alberti v Cadogan Holdings Ltd [2021] UKUT 85 (LC); [2021] PLSCS 72 provides useful guidance on the interplay between section 9(1A)(d) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967 and the “reality principle” in the valuation of the freehold of a house.

The improvements

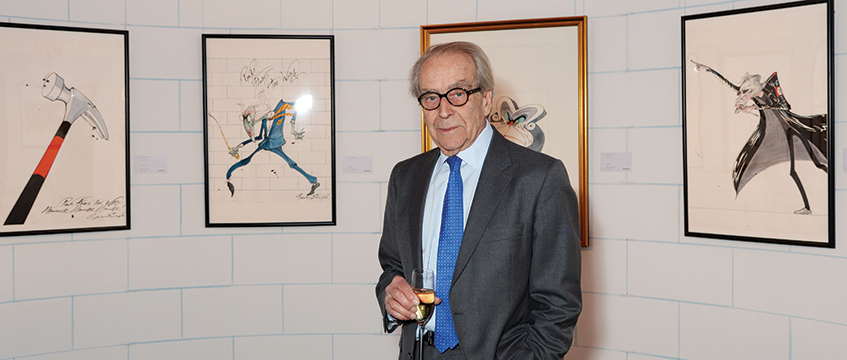

In 1971, the Earl of Cadogan granted Gerald Scarfe, illustrator and cartoonist, a long leasehold interest in 10 Cheyne Walk, London SW3. Cadogan Holdings Ltd subsequently became the registered proprietor of the freehold title to the building and Scarfe’s landlord.

When the property was demised to Scarfe it comprised five separate flats. Being no stranger to walls and the concept of taking them down, Scarfe restored 10 Cheyne Walk to a single house. The works did not involve a change of use and no planning permission was required. In 1984, the property became Grade II listed. In 1987, Scarfe obtained planning permission and listed building consent to build a studio extension.

In 2014, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea changed its planning policy. If an application had been made to restore a similar dwelling into a house after this period, it would be refused.

On 13 May 2019, Scarfe served notice of his claim to acquire the freehold on Cadogan Holdings, which it admitted. In August 2019, Scarfe sold his interest in the property, with the benefit of the claim, to Fleur Marie Alberti. Cadogan Holdings and Alberti were unable to agree a price for the value of the freehold and the First-tier Tribunal was asked to determine the same.

The assumption and reality

The Leasehold Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993 amended the 1967 Act by abolishing the rateable value limits for houses. The price payable to acquire the freehold of a house, made in accordance with the 1993 amendments, was governed by section 9(1C) of the 1967 Act.

Under section 9(1C) the price payable for the freehold was the amount which on the date the notice of claim was served, the freehold subject to the lease might be expected to realise if sold on the open market by a willing seller based on certain assumptions. The assumption under section 9(1A)(d) provided that the price payable for the freehold of a house and premises be diminished by the extent its value had been increased by any improvement carried out by the tenant or his predecessors-in-title at their own expense.

The parties agreed that the works carried out by Scarfe were improvements for the purposes of section 9(1A)(d). Further, they were carried out by him when he was the tenant under the lease, at his own expense.

The reality conundrum

As a preliminary issue, the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) was asked to determine the scope of the assumption under section 9(1A)(d). Specifically, whether as a necessary consequence of that provision, a purchaser of 10 Cheyne Walk, in its unimproved condition, would need to obtain planning permission and listed building consent if they wished to carry out work to enable it to be occupied as a single house with a studio extension.

In Harbinger Capital Partners v Caldwell [2013] EWCA Civ 492 the reality principle was described as follows: “where an amount is to be ascertained by postulating a hypothetical transaction… things are to be taken as they are in reality on the valuation date, except to the extent that the instrument postulating the hypothetical transaction requires a departure from reality”.

Alberti argued that valuation of the freehold in its unimproved state should be undertaken by reference to reality, including the planning and building control legislation and policies that actually existed on the valuation date and would have been applied to the building in is original state. It would have been unlawful as a matter of planning control to use the property as a single house on the valuation date. Further, a hypothetical prospective purchaser would have been advised of the same.

Relying on the reality principle, Cadogan Holdings argued that section 9(1A)(d) was only concerned with the physical condition of the building. The provision did not “require or permit any counter-factual assumption to be made about the use which could lawfully be made of it”. At the valuation date it was lawful for the property to be used as a single house and it should be valued as such.

The determination

Shalson v Keepers and Governors of the Free Grammar School of John Lyon [2003] UKHL 32 is authority for the proposition that, for the purposes of section 9(1A)(d), the extent to which the value of a house and premises are increased by an improvement is “simply the difference between the value of the property with the improvement in question and the value of the property without it.”

Relying on Shalson, the UT agreed with Alberti. For valuation purposes, the improvements made by Scarfe had to be ignored. A hypothetical prospective purchaser of 10 Cheyne Walk in its unimproved state would have been advised that planning permission would not be granted to restore the flats into a single dwelling. The best proxy value of the property in its unimproved state was a notional house next door that was divided into flats on the date the lease was granted and remained in that condition on the valuation date.

Elizabeth Dwomoh is a barrister at Lamb Chambers