You would have to be living under an off-grid rock to be unaware of the global energy crisis.

But developers in the UK’s cities are facing an even greater threat, as the infrastructure that powers our businesses and homes comes under ever-greater strain.

Official figures for the first quarter of this year show that total consumption of electricity by end users was 76.1 TWh. Electricity generation, meanwhile, was 84.0 TWh. In other words, there is more than enough electricity being produced.

Soon, this could not be the case. The combination of cold weather and gas shortages this winter has already led to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy to wargame the possibility of nationwide blackouts.

Its “reasonable worst-case scenario”, under which Britain faces a capacity shortfall of a sixth of peak demand – even after the emergency coal plants have been fired up – could see Britain forced to ration energy in the depths of January.

The BEIS has been keen to point out that this is not likely. “We wargame worst-case scenarios to test our ability to respond. These aren’t things we expect to happen.”

But it highlights the bigger issue. The headroom between demand and capacity is for the nation as a whole. Dig down into the detail, and in many areas, capacity has already been reached.

Power hungry

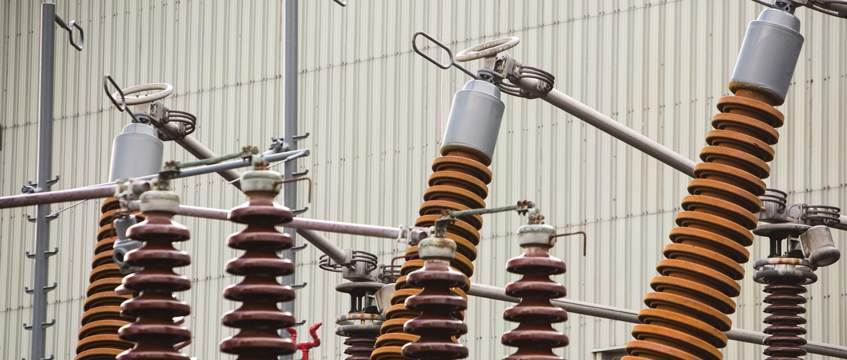

Across great swathes of the UK’s key cities, lights are flashing red. The substations and cables that provide the power to millions of homes and businesses are under extreme strain. A survey of 12 UK cities by EG showed that half were classed as ‘red’ areas according to the UK’s network distribution operators. While ‘green’ means that there is plenty of capacity for more connections to be plugged in, and ‘amber’ suggests that demand is nearing maximum capacity, the meaning of the red designation is simple: the network has reached capacity. There is no headroom.

“From a planning perspective, it hasn’t reared its head – yet,” says CBRE’s executive director of planning, Jonathan Stoddart. Right now there are far more pressing matters, he says, like the rising cost of steel. “But it is something that we need to be very mindful of moving forward and planning for properly.”

Unless the infrastructure is upgraded, though, it could be a serious issue. “We are potentially facing a situation where people could start ruling out sites because they simply can’t get access to the power,” says Stoddart. “We’re hearing a little bit of that at the moment with data centres and film studios, because they are very, very power hungry.”

Western Power Distribution, which owns the grid for cities including Bristol (red), Cardiff and Birmingham (both pleasingly green), insists that connection, even in these red areas, is still possible – however, “there might be a requirement for significant network reinforcement to overcome the impact on the network constraints”.

In other words, you’ll have to pay for the upgrades. And a new substation doesn’t come cheap.

WPD plans to invest £6.7bn between 2023 and 2028 alone. “We’ve been installing larger service cables to new-build properties for a few years now and we are now installing larger network cables ready to meet demand,” says system development manager Paul Jewell. “Many of our assets have a 50-year lifespan, so we are already building the network that will be operational when net zero is a reality.”

But that investment will take years to come online. In the meantime, if developers want to build in areas with no capacity, they will have to pay for an alternative, or wait.

Urgent upgrades

In parts of London this has already reached a head. In August, the Greater London Authority issued a warning to would-be developers in three west London boroughs. The grid, it said, did not have the capacity for significant new development until it had been comprehensively upgraded.

“Upgrades to the distribution and transmission networks will, however, take many years to complete,” the GLA said.

It said it was looking to find “innovative solutions” to “mitigate the immediate constraints”. Unless it can achieve this, “developments… may otherwise be delayed or stopped in their entirety”.

“That is jaw-dropping,” says Forsters’ head of real estate Andrew Crabbie. “This is an absolutely massive issue for developers.” He says he has clients who have walked away from buying sites because of the uncertainty surrounding whether or not the would be able to access power.

“Our advice to clients is that you can’t even consider bidding on the site unless you’re comfortable with the power sources,” says Crabbie. “Don’t even go near it.”

So far no other UK authority has issued such a stark warning. But the likelihood of them doing so is high. “This area of the country has got data centres pushing the lack of supply over the edge,” says Crabbie. “But the rest of the country is pretty near the edge as well.”

The red patches covering the national network heat map like a plague of boils show how close demand is to exceeding capacity. And it is only going to get worse.

Last month the BEIS and Ofgem published a blueprint for energy supply, catchily titled Electricity Networks Strategic Framework: Enabling a secure, net zero energy system.

The demand for electricity, it said, would more than double by 2050, and the current network is simply not able to cope. “The network needs to be transformed at an unprecedented scale and pace to accommodate decarbonisation and demand growth,” it said.

At the moment the UK uses around 330 TWh of electricity a year. That might be a little hard to picture, so think of it like this. Let’s say you built a reasonably energy efficient, 20,000 sq ft office building. You’d better build it to last, because 330 TWh would be enough to power it for the next million years.

330 TWh is a ridiculously large figure, but it is about to get even bigger. By 2035 demand is expected to reach 500 TWh. By 2050, it will be 770 TWh.

The BEIS and Ofgem predict that this will come from a combination of organic growth, switching from less sustainable supplies and the rise of electric vehicles – 720,000 public chargepoints alongside millions of private ones.

Complete overhaul

But the real issue comes with peak demand. System peak demand is currently around 58 gigawatts. That means the grid has to cope with the equivalent of 700m electric kettles being boiled simultaneously.

By 2050 that is predicted by BEIS to more than treble to between 130 and 190 GW. To cope, production will have to be greatly increased. Hence the prime minister’s call for a new nuclear power station every year. But the network that conveys this power to end users will need to be completely overhauled, too. Capacity is mostly limited by substations and cables, which will need to be ripped out and replaced with much bigger, better kit as the need for electricity in our city centres more than doubles.

It will not be cheap. The BEIS estimates that the cost of upgrading the network to cope with all this will reach £110bn by 2050.

And it will not come quick. The report states: “Identifying where new transmission infrastructure is required, securing planning and regulatory consent and building this infrastructure takes over a decade.”

Nor will it come quickly enough, the BEIS admits. “The lengthy delivery timeline… is likely to place further pressure on an already constrained transmission network.”

Compensation for such constraints on supply currently stands at around £500m a year. But the BEIS and Ofgem predict that this will rise to as much as £2.5bn in the mid to late 2020s. They are acknowledging that, even in the best scenario, supply will not meet demand. And that can only be bad news for development.

As Forsters’ Crabbie says: “Deals that were previously conditional on planning are now conditional on power.”

To send feedback, e-mail piers.wehner@eg.co.uk or tweet @PiersWehner or @EGPropertyNews