This week, planning fees for major projects rose by 35% to reach a maximum of £405,000 an application. But despite the rise, an increasing number of developers say they would be more than happy to pay more – far more – in exchange for a little certainty.

“I would have absolutely no issue whatsoever in paying several hundreds of thousands of pounds more,” says Socius managing director Barry Jessup. And he is far from alone. Birchgrove’s chief executive, Honor Barratt, echoes the sentiment. “Honestly,” she says, “there is – almost – no size of cheque that I wouldn’t write to get my planning permission within 13 weeks.”

The resounding cry from the development sector is one that you would think would be irresistible to the Treasury: “Just take our damn money!”

That’s because the developers are losing so much more dealing with an under-resourced and failing planning system. “We are working on large projects where time is of the essence,” says Jessup. “If you’ve acquired a site and you’ve got £50m on your book, that is costing you the best part of half a million a month in finance costs.” A delay of just four weeks could cost more than the heftiest planning fee, even after the recent hike.

Until this week, the cost of a major application for more than 50 homes or 3,750 sq m of floorspace was £22,859, plus £138 for each additional dwelling or additional 75 sq m up to a maximum of £300,000. From this week, that will rise to £30,860, plus £186 for each additional dwelling or additional 75 sq m of commercial space, up to a maximum of £405,000. And it is expected to rise annually with inflation.

Positive steps

But whether the planning application fee is “fifty grand, 250 grand or 450 grand really doesn’t matter in the scheme of things”, says Jessup, breaking down the numbers. “Let’s use a £250m project. Typically, the land price might be in the region of £30m. Your planning costs – design and all the rest – are probably something like £4m. And then, of that £4m, the planning application fee is about £150,000.

“Frankly, the planning application fee as a percentage of even our planning budget is de minimis,” he says. “It’s nothing.” Putting it up by 35% isn’t even going to touch the sides.

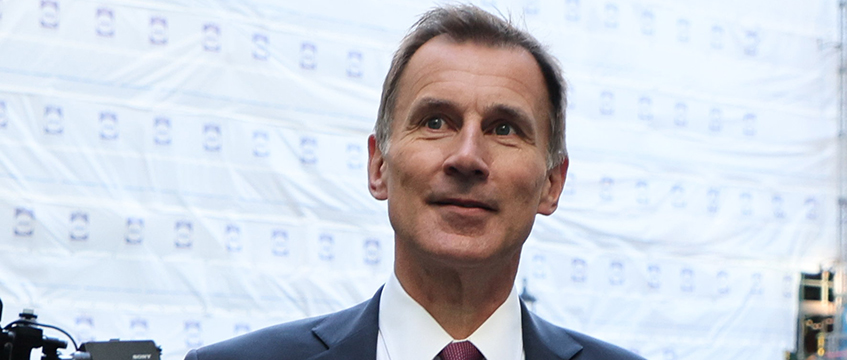

Neither is the other flagship planning reform unveiled by the chancellor in his Autumn Statement. Jeremy Hunt promised that developers of major schemes would benefit from a “premium planning service” from next year, supported by a money-back guarantee.

He called it “a prompt service or your money back – just as would be the case in the private sector”.

It sounds promising, but in effect this is simply extending the existing patchwork of planning performance agreements. As Mark Smith, group development director of developer London Square, says, developers already have to agree planning performance agreements for most schemes. The problem is “the majority of planning authorities still can’t provide the level of service needed to progress projects in a timely manner”.

Mike Hood, chief executive of Landsec’s regeneration business, says the effective extension of PPAs was a “positive step”.

“However, for it to have a meaningful impact, it needs to be accompanied by a comprehensive set of measures,” he adds, like those set out in a policy paper Landsec produced with British Land. “We need to ensure proper resourcing of the planning system, reduce the layering of planning policy and address the viability challenges of urban regeneration.”

To this end, Hood and colleagues have been lobbying not only this government, but the party likely to form the next one. “We have been pleased with engagement from both parties so far on this issue and look forward to further progress in the new year,” Hood says.

Dwindling resources

The problem is not that planning authorities don’t want to put the applications through in a timely manner, or that developers are putting forward contentious or unwanted developments. The problem is a desperate lack of resources.

The overall cost of processing planning applications across England stands at approximately £675m a year. But the money pulled in annually by planning fees amounts to just £393m. Some other funding is gleaned from arrangements with developers, such as planning policy agreements, but despite this there is still a funding shortfall for the service, estimated by the government to be in the region of £225m annually.

Even if that gap were to be closed, which would require application fees to be raised by at least 50%, that would still only pay for the current level of service, which most agree is not sufficient.

“We support the idea of local authorities recovering costs where they meet agreed timescales and service levels,” says Michael Meadows, head of planning at British Land. “But we require assurance that these additional funds will be dedicated to building capacity and capability, with a long-term focus on the planning profession’s skills pipeline and attractiveness.”

None of us wants the job of being a local planner because they are so under-resourced and are frequently working in a hostile environment. So, anything that can be done to help them recruit and retain talent must surely be a good thing

Honor Barratt, Birchgrove

The level of underfunding is profound. A recent National Audit Office report concluded that between 2010 and 2020, £1.3bn worth of funding had been stripped from planning departments.

As C|T Local’s John Walker says: “Putting up planning fees by 35% for major applications… will not solve the resource problem in planning departments.”

Meadows adds: “The current system is overburdened, with complex interactions between local, regional and national tiers, resulting in policy layering and duplication. Streamlining the planning system will ensure that any additional funding and resources can be deployed most effectively and efficiently.”

Streamlining should not mean fewer planners. The shortage of funds has already led to a hollowing-out of planning authorities. According to the RTPI, the proportion of planners working in the public sector has fallen from around 70% to under 50% in the past 15 years. The data shows that 25% of planners left the public sector between 2013 and 2020. Over the same period, the private sector swelled by two-thirds.

Only one in ten council planning departments are fully staffed, with a national vacancy rate of 14%.

A 2022 survey by the RTPI showed that a fifth of local planning authority respondents “never have enough time” to carry out assigned workloads. Half said they encountered time crunches at least periodically. The most cited reason was the “lack of staff resource”, as employees often have to cover for missing staff.

Salaries have barely risen since 2005, meaning that in real terms they have shrunk by a third. The RTPI said that around 15% of council planners were looking to quit the profession. Another 24% are just looking to leave the public sector.

Local authorities are struggling to attract talent, and that is bad news for developers. As Barratt says: “None of us wants the job of being a local planner because they are so under-resourced and are frequently working in a hostile environment. So, anything that can be done to help them recruit and retain talent must surely be a good thing.”

A 2022 survey by the RTPI showed that a fifth of local planning authority respondents “never have enough time” to carry out assigned workloads. Half said they encountered time crunches at least periodically. The most cited reason was the “lack of staff resource”, as employees often have to cover for missing staff.

Salaries have barely risen since 2005, meaning that in real terms they have shrunk by a third. The RTPI said that around 15% of council planners were looking to quit the profession. Another 24% are just looking to leave the public sector.

The problem is that the level of resource being committed by central government is insignificant compared with the scale of the problem.

“The chancellor’s Autumn Statement announced £32m to ‘bust’ the UK’s planning backlog,” says James Blakey, planning director at Moda Group. “But the RTPI concluded that a £500m investment in the system is required to achieve the government’s climate and levelling-up aims.”

In fact, the £32m amounts to a less than 1% increase in total council spending on planning.

According to the RTPI’s State of the Profession, published last month, total public expenditure on planning services in England has contracted from £1.4bn in the 2009-10 financial year by 16% to £1.17bn in 2022-23, when adjusted for inflation.

At the same time, income from planning services has increased by 14% from £507m to £577m.

The problem is that the growing income from planning services is not being translated into more money spent on planning.

As the RTPI says, this is because direct public investment in planning has been decreasing. Real net current expenditure on planning services has declined by a third since 2010, from £893m to £594m.

And although the government has insisted that the increased fees would be used to pay for improvements, it has so far failed to enshrine this in law. An opportunity to include the measure as an amendment to the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act was missed, and the government is now proposing to use a letter from the chief planner instead, which has no weight in law and can easily be overlooked by a cash-strapped local authority sinking under the weight of its homelessness obligations.

“Unless the additional income is ring-fenced, I’m sceptical about whether this will have the desired effect in practice,” says Raj Kotecha, chairman and chief executive of residential developer Amro Partners.

And the problem is not only at the local level. This week, the fate of two applications showed it exists at the regional and national level as well.

In Cricklewood, Montreaux was granted outline approval for its redevelopment of a former B&Q site that it wants to develop as 1,046-home scheme. But the approval came after more than two years, after the scheme was called in by the secretary of state, Michael Gove, and the planning inspector’s report was then sat on for nearly six months.

Meanwhile, Gove has said he will call in MSG’s plans for its 300ft tall Sphere in Stratford, E15. This should be good news for the developer, as the £800m project was approved by the London Legacy Development Corporation, but then blocked by London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan. Gove’s intervention, in theory, gives MSG another chance. But the developer isn’t interested. There is too much uncertainty, it said, literally taking back its ball (and selling its site) and moving on to play somewhere else. Why should it waste more time and money on the capricious English planning system, the argument goes, when countless other cities would leap at the chance to have what it is offering?

Deadlines and costs

The measures being proposed by the government will not address the real problem, say critics. “The development sector couldn’t care less about refunds,” says the BPF’s head of planning, Sam Bensted. “All they want is certainty around deadlines and the costs. Not the costs of the application, but the costs of delay to projects and the uncertainty surrounding that.”

And there is more at stake than mere money. As Birchgrove’s Barratt says: “The cost of not building is huge to me as a developer – every week that a site sits in planning is, of course, expensive to us, the developers. But it is also huge to those people in this country who currently don’t have a place they can call home.”

The Local Government Association has predicted that local authorities face a £4bn funding gap next year, and that is just to stay still. Every other week we are seeing another example of a council issuing a section 114 notice as they struggle to control their deficits. Another 60 English councils have warned they are at risk next year, with the LGA predicting that 12 will issue notices.

As Jessup says: “If we don’t get a planning application through, the fact that we would get the planning application fee back is a drop in the ocean. It really doesn’t make a difference to us. But this will make a big difference to the councils. Nearly every council we speak to is virtually bankrupt. And that money is significant to them.”

The latest hike in planning fees and the chancellor’s “money-back guarantee” are not the solutions that are needed. “But,” Bensted says, “it has to be a positive thing that we’ve got a private sector that is very vocally saying, ‘We are willing to put more money in to get this system working better.’

“How do developers fix the planning system, I guess, is the million-dollar question,” he says. “But at least they are asking the question.”

To send feedback, e-mail piers.wehner@eg.co.uk or akanksha.soni@eg.co.uk or tweet @EGPropertyNews