For chancellor George Osborne, a focus on scientific innovation and hi-tech manufacturing provides at least part of the answer to the question of how the UK can escape the economic doldrums.

In his Conservative Party conference speech last October, Osborne noted the importance of getting Britain “making things again” as he unveiled a £50m funding pot to aid the development of a new miracle material called graphene, following its discovery by scientists in Manchester.

As a result of this specialist funding – and Manchester’s involvement in the development of graphene – it is tempting to envisage some sort of gold-rush to the city, culminating in a cluster of graphene-related industries in the southern corridor close to the universities, with obvious implications for the property market.

While the potential for such development exists, experts warn that the spin-offs from graphene may take many years to emerge. Nonetheless, they argue, the potential for economic growth led by scientific innovation in Manchester, remains strong.

National Graphene Institute

The University of Manchester has been confirmed as the sole supplier invited to tender for a proposal to fund a £45m National Graphene Institute, described by the scheme’s project manager, Ivan Buckley, as a facility “where academics and businesses will have access to state-of-the-art equipment, facilities and leading research”.

The university’s Professor Andre Geim, who was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for work on graphene in 2010, says the institute “would allow our world-class scientists and researchers to further explore the limitless potential of graphene”.

Yet the university is downplaying the imminent likelihood of a physical cluster of shiny new labs and buildings arising from this investment. Rather, funding would be ploughed into research work and staffing.

“We will work with external researchers, scientists and engineers from the UK and beyond, as well as business – be it multinational corporations or SMEs,” says Buckley. “An important facet of the investment will be the development of new companies through spin-outs, utilising the university’s facilities and resources for start-up and support.”

Mike Emmerich, chief executive of Greater Manchester economic development body New Economy, believes graphene is crucial for the city’s economy. Speaking at MIPIM earlier this month, he suggested Manchester should make efforts to capitalise on the discovery to spur growth.

However, Jane Davies, chief executive of Manchester Science Park, suggests that graphene is at a very early stage in terms of commercialisation.

“It’s very exciting, cutting-edge science, but it will be some years before commercial applications are developed anywhere,” she says.

“Our plan for development of the science park is based on the next five years, so the success – or otherwise – of graphene is not especially relevant. But graphene is very important in terms of perceptions of Manchester on the world stage – it shows we are an innovative place where new discoveries continue. So it makes Manchester a more exciting destination for companies to invest.”

Growth plan for Manchester Science Park

A growth plan for MSP was published early last year and envisages adding around 250,000 sq ft of development, including a first new building of up to 70,000 sq ft. Developer Bruntwood is in advanced talks to take a controlling interest in MSP – whose current shareholders include the two main Manchester universities and both Manchester and Salford city councils – in order to drive development.

MSP already owns two potential development sites – one at the corner of Denmark Road and Lloyd Street North, and the other off Greenheys Lane at the west of the existing site.

In a joint venture with Bruntwood, it is also redeveloping the former Royal Eye Hospital site on Oxford Road – recently renamed Citilab – to provide 100,000 sq ft of offices, labs and teaching space focused on the biomedical sector.

The scheme, designed by Sheppard Robson, achieved planning consent in 2011. Lend Lease has been appointed as contractor, and work on the scheme is due to be completed at the end of 2013.

Tony O’Brien, partner and design director at Sheppard Robson, says the firm retains a strong interest in science and health-based projects. It is also bidding on the Royal Liverpool Hospital development in Liverpool, and O’Brien suggests such schemes can be viewed in commercial terms.

“It’s like a retail development,” he says. “You need an anchor tenant – in Liverpool, that’s the hospital – and that leads to other stuff around it. A graphene hub in Manchester could potentially act in the same way, and will work as a catalyst for other research facilities nearby.”

With work ongoing on this scheme, and the potential growth of the science park, Manchester appears to be in a strong position to harness the economic benefits of science-led growth. And should graphene become the true 21st century miracle material its proponents suggest it could be, Manchester will be in pole position to exploit its commercialisation.

What is graphene?

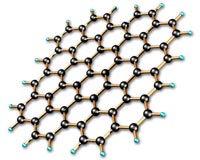

Graphene is a super-thin, super-flexible, super-conductive material discovered by University of Manchester scientists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, who received the Nobel Prize for their work in 2010.

The discovery was based on stripping down layers of a form of carbon – like the graphite used in pencils – to just one atom in thickness. Three million such layers would be needed to create a 1mm depth. It has been calculated that a stack of layers with the same thickness as a sheet of clingfilm could support an elephant.

Potential applications include replacing silicon as the basis of the standard microchip, flexible touchscreens and mobile devices, and lighter, stronger prosthetic limbs.

How long from from scientific discovery to property pay-off?

Graphene has already been billed as “the new silicon” in recognition of its potential to deliver a technological revolution along the lines of the silicon chip. So, for an indication of the likely impact of graphene in property terms, it is worth considering how silicon led to the birth of Silicon Valley in California.

While the origins of the silicon chip can be traced back to the late 1940s, it was another decade or so before the first integrated chip – which forms the basis of modern computing – was invented. In turn, it was the early 1970s before the phrase “Silicon Valley” was first used to describe the cluster of hi-tech businesses in the southern San Francisco Bay area of California.

In other words, the translation from discovery to self-sustaining property market took more than two decades.

For a brief time in the 1990s, Silicon Valley became home to the most expensive real estate in the world, proving that scientific discovery can, eventually, lead to major property returns. Yet the subsequent burst of the dotcom bubble showed that development based on innovation can be a temperamental business.

Closer to home, the Roslin Institute – which, in 1996, cloned Dolly the Sheep near Roslin in Midlothian – recently relocated to a £60m building in Edinburgh. But the connection between this famous experiment and the institute’s new premises should not be overplayed. A spokeswoman explains that the scientists who worked on the cloning experiments left Roslin before the new facility was conceived. Nonetheless, the building does, when viewed from a certain angle, bear a striking similarity to a pair of chromosomes.