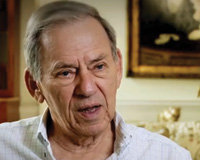

Tower 42 owner Natie Kirsh has a career stretching back to the coronation. He talks to Damian Wild about 60 years in business

n 2010, the high-profile battle for the control of Minerva thrust Natie Kirsh into the London spotlight. And his acquisition late last year of Tower 42 in the City has kept him there. But the 80-year-old South African is one of the few active players on the UK property scene who was already forging a career in business when the Queen came to the throne. Kirsh, who rarely gives interviews, makes an exception for this Estates Gazette Diamond Jubilee special.

It was in 1952 that Kirsh graduated from the University of Witwatersrand and threw himself into running the family malt business in Potchefstroom in the North West Province of South Africa. He had already travelled with his father on business trips to sell malt while still at school. And now, with his mother running the business since his father’s death four years earlier, Kirsh took over, modernising the operation.

His business interests began to take off in 1958. Leaving his brother Issie running the family firm, Kirsh crossed into neighbouring Swaziland, then one of the last outposts of the British Empire.

His approach to British diplomat Patrick Forsythe Thompson with a proposal to open a brewery in Swaziland was turned down. The rights had already been promised to Swaziland’s Second World War veterans. Instead, Kirsh was asked whether he would be interested in opening a maize mill.

“What amazes me is I had £1,200,” he says now. “They didn’t know me from a bar of soap.”

He negotiated terms, but his £1,200 – inherited from his father – was never going to be enough to get a maize business off the ground.

“They never asked me if I had any money, how I was going to do it, or what was I going to do. I came back to my little home town and went to speak to my bank manager. Then I did a bit of homework and found I needed £45,000 in capital expenditure on the mill and that little malt factory I was going to build, and I needed £100,000 of working capital.

“I knew the bank manager in Potchefstroom had a high opinion of me because one of my pals was his clerk. And he had written – they make assessments of all their clients – to Pretoria, which was the regional office for the bank, and said, ‘This is the smartest young business guy in town.’ That was my credit. So I went to the bank manager, I said, ‘I’ve got this fantastic agreement, it really is a no-brainer, it will give me a real start.’

“The bank manager said, ‘I can lend you £2,500 without going to Pretoria. I can lend your brother £2,500.’ That gave us £5,000. He said, ‘Register a company and I can lend the company £5,000.’ So now we had £10,000. But my brother had £1,000 and I had £1,250 so now were up over £12,000. But we still needed to get to £45,000. We got some money from my mother, and then I went to all my business pals and said, ‘If you want to come into business with me you’ve got to put in a pound of equity and a pound of loan capital.’

“I went to the bank again and it wasn’t really all that tough, because grain really is a very liquid asset. And so they gave me an overdraft of £100,000 for working capital.”

That was all he needed to get started.

“Soon the sheds were full, and the maize was stacked outside. We blew through our overdraft and the bank manager became extremely nervous. I said to him, ‘Listen, we’re in too deeply. I’m writing cheques; you’d better keep paying them. Shortly after that the mill was finished, and we finished the first year with a £1,400 profit.”

Kirsh moved on from malt and maize into fertilizer, farm chemicals and packaging. In year two he made £10,000.

“The rest is history,” he says. “I became the most dominant business person in the country and just did pretty well at everything. I had phenomenal exposure to do things and see things that I would never have seen or done in a bigger society. The British government recognised that I had some kind of talent and at a very young age I became chairman of the electricity board. And by my early thirties I was at the World Bank, negotiating loans for the country, building power stations.”

Kirsh is still active in Swaziland, running philanthropic organisations funding small businesses through the Inhlanyelo Fund and the Computer Education Trust, which has installed computers in all schools in Swaziland.

There aren’t many businessmen who have enjoyed Kirsh’s level of success in so many different parts of the world. His career has seen him become one of South Africa’s most successful entrepreneurs. In a 15-year spell he built the country’s third-largest industrial conglomerate. At its peak in 1984, his holding company, Kirsh Industries, controlled revenues of 2.3bn rand and employed a workforce of 40,000. When PW Botha’s Rubicon speech in 1986 led to the sudden withdrawal of all foreign investment from South Africa and caused the economy to slump, Kirsh sold the company at a knockdown price.

Undeterred, he moved to New York and grew what is now one of the US’s largest private companies, Jetro/Restaurant Depot. The company’s sales are thought to be around $7bn (£4.5bn) a year, dominating food distribution in major cities and supplying more than 350,000 restaurants in major cities across the country.

But property has always been an interest. By the mid 1950s he was taking early steps, developing Tanrod Flats behind his parents’ home. Jetro itself came about as Kirsh was pursuing what would have been a career-making property deal in New York. His current property interests, now the responsibility of former Lambert Smith Hampton chief executive Philip Lewis, include long-term investments and developments in Australia, South Africa, Swaziland and North America, as well as the UK.

For Kirsh, the major changes over the course of his 60-year business career have been technological. “The computer has changed the whole world of business. It has changed how businesses are run. It has changed how businesses are managed,” he says. “I remember working in my mother and father’s business, and three months after the end of the financial year I used to be looking over the bookkeeper’s shoulder to see what our profit and loss was. Now I wake up on Sunday morning, I pick up my Blackberry and I can see the trading results up to Saturday night at my American business.”