The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard takes effect in less than three years. Charles Woollam and Peter Williams suggest how landlords of commercial buildings can prepare for it

Types of works required by MEES

- Improved insulation of walls, doors, roofs and windows

- Installation of renewable energy sources

- More efficient heating, cooling and lighting systems

- Installation of energy metering

- Measures specified in an EPC recommendations report

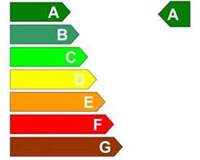

The regulations that will govern the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard (MEES) have now been made. Guidance is awaited from the government on some of the details but two things are already certain. First, a significant administrative burden is now attached to commercial buildings rated F or G. Second, in some (although not all) cases, significant costs will need to be incurred to achieve compliance.

The regulations

From 1 April 2018, under the Energy Efficiency (Private Rented Property) (England and Wales) Regulations 2015 it will not be lawful to grant or renew existing leases of “substandard” buildings until either sufficient energy efficiency improvements have been made or landlords can show that either MEES does not apply or that they fall within an exemption. In April 2023, the requirement will be extended to all leased buildings. “Substandard” means buildings that have an EPC rating of F or G. The government believes that the new regulations will affect approximately one in five buildings (although in reality no one has any idea, since there is still an unknown number of uncertified buildings).

The regulations require substandard buildings to be brought up to at least an E rating, but the obligation to make improvements is effectively capped by a financial test. Broadly, works only need to be carried out if they are cost-effective. If the cost of an improvement is less than the predicted energy cost saving over seven years, it is considered to be cost-effective. If the building is still F or G rated even after all the required cost-effective works have been undertaken, an exemption applies and the property may still be let. Works that are carried out under a green deal plan are also considered to be cost-effective and therefore need to be undertaken. However, there is currently no sign of a commercial green deal.

The types of works required by MEES are those listed as “consequential improvements” in Part L of the Building Regulations, so long as they are contained in an EPC recommendations report or a surveyor’s report.

The first step in an effective strategy to ensure compliance with the regulations is to identify which buildings are affected, and develop a strategy for each affected building. One approach is to place each building into one of five categories: excluded, compliant, uncertified, substandard, or exempt.

Excluded

Some buildings and lettings are excluded. If a building does not require an EPC (if it is listed, for example), it is outside MEES. Lettings for 99 years or more, or for up to six months, are also excluded. In these cases, MEES is not an issue.

Compliant

According to the latest figures (from 2012), around 80% of buildings with EPCs are currently unaffected by the new regulations because they have ratings of E or better. However, EPCs are valid for a period of only 10 years, after which they will need to be renewed. It is expected that the rating of some buildings will slip on re-certification, because of changes to EPC methodology or because existing certificates do not reflect recent alterations.

It is also possible that the minimum standard will be raised in the future. Although E-rated buildings meet the minimum standard now, there is still a degree of risk attached to these buildings.

Uncertified

A building is not within MEES until an EPC is obtained. 550,000 “lettable units” currently have an EPC but it is not known how many more buildings are currently uncertified. For uncertified buildings, landlords should consider certification now or risk missing opportunities to make improvements when a building is vacant (when the cost will probably be lower). However, landlords need to be aware that obtaining an EPC early may bring a building into MEES, so this needs to be carefully considered.

Substandard

Buildings rated F or G can be divided into three categories: those that will achieve a better rating if they are certified more accurately; those that can be brought up to the minimum standard by carrying out cost-effective works; and those that will not reach an E rating even once all such works have been done.

It may be unwise to take current EPC ratings at face value. In many cases, especially in the early days of EPCs, inadequate information was provided to assessors and default assumptions were used to calculate the rating. The methodology has also changed on several occasions and revised certificates are not always obtained when material changes to buildings are made. One fund manager has apparently rid itself of virtually all its substandard buildings simply by having them assessed more accurately. It is equally possible that ratings will drop on re-certification, so care is needed.

Where works are needed, an assessment will need to be done to identify whether each potential improvement passes the seven-year payback test and whether the combined effect of some or all of those improvements is sufficient to move the EPC rating to a minimum of E. There may be several combinations of works (“bundles”) that will deliver the minimum standard. Landlords should identify the best bundle for each building. For some, it will be a matter of complying with the minimum standard at the lowest cost. For others, it will be more a question of choosing the bundle that produces the highest energy cost saving or that maximises the recovery of costs from tenants. Some works will have little measurable impact on investment values but others might be incorporated into general improvements that will improve investment value.

The timing of works will also need careful planning. Costs will usually be lower if the work is planned to coincide with voids. However in that case it may not be possible to pass on the cost of improvements to tenants under the terms of modern commercial leases. In other cases, landlords may be able to negotiate contributions from tenants or undertake works to occupied buildings as part and parcel of general maintenance and repairs.

Research recently undertaken for the Green Construction Board by Sweett Group, SIAM and Kingston University also shows that there is often merit in targeting a higher rating than the statutory minimum. Although it may cost more to achieve a D rating, for example, the energy cost saving is often disproportionately higher. The research also showed that it will usually cost very much less to move a building from F or G straight to D than to do so in two stages. A solid D rating will provide more effective protection against future “ratings slip” or any subsequent uplift in the minimum standard.

The research for the Green Construction Board also showed that many buildings will retain their substandard rating when all the qualifying work has been done. This is particularly the case for air-conditioned offices because costs are generally high in relation to the savings potential. In these cases, a decision will need to be made whether to claim an exemption or to improve the rating voluntarily.

Exempt

There are a number of exemptions from MEES, of which the key ones are that all cost-effective works have been done but an E rating has not been achieved, or that any necessary consents for the works cannot be obtained. This sounds like a get-out from MEES, but examining the detail shows that this is not necessarily the case.

Exemptions will only be valid when recorded on a public register, and landlords must be able to prove that the exemption is valid if challenged. Exemptions expire after five years, after which the landlord will need to register a new one (which might first require works to be carried out). Exemptions cannot be transferred to a new owner when a building is sold. This means that investors will need to develop a process for assessing, registering and renewing exemptions. Exemptions will no doubt also be scrutinised closely by prospective purchasers when buildings are sold.

Landlords will need to consider carefully whether to rely on exemptions, as it is likely that a substandard building may not be as attractive to tenants, and its rental and capital value might be adversely affected. However, it is wrong to assume that the value of all F and G rated buildings is equally at risk. Much will depend on local supply and demand issues. In some cases the works may fail the seven-year payback test because the savings are too low. However, the cost of the works may equate to only a few weeks’ or months’ rent. In these cases it may be preferable to ignore the exemption and do works voluntarily to improve the rating to an E (or even a D) to avoid the risk that value will be compromised.

Charles Woollam is a chartered surveyor and partner at Sustainable Investment & Asset Management LLP (SIAM) and Peter Williams is a training consultant with Falco Legal Training