Sharp rises in sales and values over the past year, combined with weak growth in rents, have led to increased talk of a commercial property bubble. What is the evidence that we are in a bubble that is in danger of bursting?

A comparison of the market now with the market in 2006/07 demonstrates why this cycle has further to run.

The year to Q3 2007 saw investment sales in Europe of €273.2bn (£198.4bn). In the year to Q1 2015, the equivalent tally was €238.9bn – 12.6% less. So even if we believe that we are repeating the 2007 peak, we have some way to go to equal it.

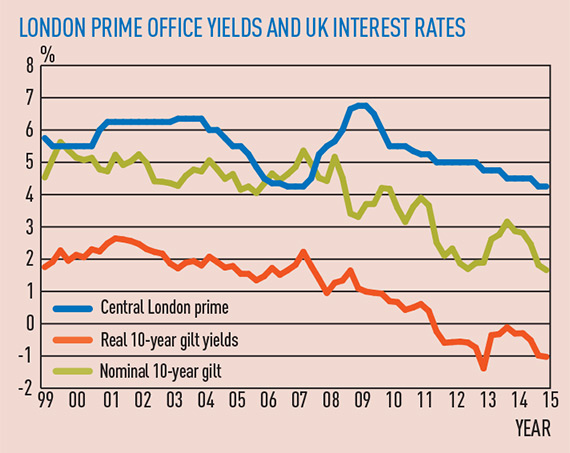

There are also differences in relative pricing. Between the end of 2005 and 2007, prime West End office yields actually fell below UK 10-year government bond yields. In Q1 2015, the gap was more than 200bps, a near historic high. As property is a real asset (containing some inflation proofing), an even better comparable is real interest rates. The spread of the same prime yields over 10-year index-linked gilts in Q2 2007 hit a historic low of 127bps compared with 468bps at the end of March.

Looking at other UK and continental European property markets, relative pricing differentials between prime and secondary are much wider than in 2006/07; so that other sign of a bubble, the mispricing of risk, is also reassuringly absent.

There are also differences on the occupier side. In 2007, the European (and world) economies were at the tail end of a long boom. EU GDP had grown pretty much continuously since the early 1990s, accelerating post 2000. For Q1 2015, EU GDP has only just clawed back to the Q1 2008 peak. Likewise, real office rents for Europe as a whole at the peak of the last boom were 17% up on December 2004, while real rents have only just started to recover after a long downwards slide.

2006/07 was the top of the economic cycle and rental growth was being extrapolated to justify yields that were very low relative to interest rates. This was an accident waiting to happen. When the recession came, the development boom initiated by previously high rents exacerbated the erosion of rents and values. In many western European markets outside London there is currently no sign of even a nascent development boom (and even in London a major upturn in new developments is still some way off).

Today, calling a bubble depends on two things: whether you think the European economy is going to continually under-perform (or that it is heading for a triple-dip recession) and/or if you expect interest rates to suddenly take off. With respect to the European economy, we can never rule out another crisis but, for me, it looks stronger than for some time.

On interest rates, the recent bond market correction has provided food for thought, but while 10-year nominal gilt yields have crept up to 2%, the spread with property yields is still wide and real interest rates have changed little. Eurozone real and nominal rates have increased, but remain near historic lows and real rates are still negative in real terms. Further, despite rumours to the contrary, QE looks likely to lock in low interest rates until September 2016 at the earliest (possibly sooner in the UK). Even then, any increase will be gradual and when rates do rise the existing spread between yields and interest rates provides a big cushion for future adjustment.

The market will turn eventually, it always does, but 2015 is not 2006. There is every reason to believe that the current run has a few years left in it yet.

Neil Black, head of EMEA research, CBRE