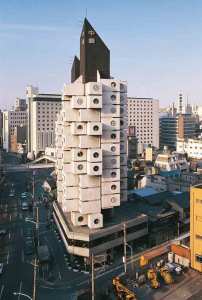

VIDEO: The Nakagin Capsule Tower is a rare relic. A leftover piece of Tokyo’s architectural and cultural history and the world’s first capsule apartments built for permanent use.

VIDEO: The Nakagin Capsule Tower is a rare relic. A leftover piece of Tokyo’s architectural and cultural history and the world’s first capsule apartments built for permanent use.

More than 40 years on, the template for the compact living trend which later gained momentum in major cities across the world has hardly changed since its completion in 1972. No renovations. No updates. No refurbs. It is effectively a real-estate time capsule. Packed full of the cutting-edge space-saving design innovations of the time. So what does it feel like to stay in this beacon of 1970s modernity in 2015? And how does it compare to today’s alternatives?

Put simply, it is as close to spending the night in a spaceship as someone who has never actually spent the night in a spaceship can imagine. But looking down over the Tokyo skyline through a tiny round window in a white capsule feels pretty intergalactic.

From the outside, the geometric building, designed by the late Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa, resembles a stack of Lego bricks piled on top of each other; it is so distinctive I only have to show my taxi driver a photo and he’s already starting the meter. Originally, the 14-storey building was created to provide functional housing for single white-collar workers in the city; bed, desk, fridge, are all tucked away in fold-up cupboards and fitted into the walls of the 140 individual pods. Effectively this was the original bachelor pad.

I am staying in one of the 30 capsules that have remained in use. The rest are used for storage or have crumbled into disrepair. Several of the capsules are rented out through AirBnB, which is how I find myself inside a room I cannot actually fit into if I lie down with my arms outstretched. The bed is less than 80 inches long and fills all of one wall.

I can quickly understand why so few capsules are now in use as full-time housing. They are tiny, the lobby and lift area is run down, and as the windows can’t be opened, it smells more than a little musty. And – particularly unwelcome as I arrive on a balmy summer’s day – there’s no hot water in the semi-bathroom – yes, with the shower over the toilet it only counts as half a room by AirBnB standards.

I can quickly understand why so few capsules are now in use as full-time housing. They are tiny, the lobby and lift area is run down, and as the windows can’t be opened, it smells more than a little musty. And – particularly unwelcome as I arrive on a balmy summer’s day – there’s no hot water in the semi-bathroom – yes, with the shower over the toilet it only counts as half a room by AirBnB standards.

But the buildling’s legacy must not be underestimated. While Nakagin was one of the first pioneers of capsule living, so-called ‘micro-apartments’ are increasingly big business in densely populated cities.

In Hong Kong, property mogul Li Ka-Shing built 196 mini-flats into a larger development on the island last year. These flats, while among the cheapest available in Hong Kong at the time, measured from just 177 sq ft, including a 97 sq ft living room, a 13 sq ft kitchen and a 31 sq ft bathroom. Reportedly all the mini apartments sold within half a day.

In Japan, it was the 1990s when kyosho jutaku – or mini homes – really first exploded in popularity, particularly on underused urban land. This in turn sparked demand for creative interior design and a national obsession with tiny but liveable spaces. Retailer Muji, known for its pared-down aesthetic, launched a prefab micro-dwelling, the Vertical Home, in 2014.

And the trend has stretched beyond Asia. In 2012 New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a programme that tasked designers and architects with designing a clever, liveable, 300 sq ft living space, with the winning model to be used in new apartments in a Manhattan development.

Take a virtual tour of the room

The motivations for these micro homes are often the same as the original plan for Nakagin, an affordable home for young urban professionals. Today, new homes have a very short market lifecycle; the average lifespan of a home in Japan is only 38 years, compared to 100 in America. Often, Japanese homeowners will buy a house only to demolish it, meaning houses are not seen as investments. But, given the high costs of construction, well-designed prefab micro homes can offer a value solution, and they are generally a cheaper option.

The value of land has been rising too, particularly in central Tokyo. Land values in Ginza rose by 9.6% between 2013 and 2014, according to government figures, costing as much as ¥29.6m (£153,000) per m2 for commercial land. In Chuo ward, the most famous part of Ginza, land prices rose by 6.5% just in the first nine months of 2014.

Back in Nakagin, and the changing market has not gone unnoticed. In 2007, the residents grouped together to raise concerns, citing squalid, cramped conditions and concerns about asbestos and earthquake protection. They voted to demolish the building and replace it with a larger, modern tower. This plan stalled because the financial crisis hit, and it proved impossible to find potential developers. And so the fate of Nakagin remains uncertain.

“Residents have quite diverse opinions over what should happen”, says my landlord for the night, Ryotaro Suzuki. “Some really hate the tower whereas some really love it. The real estate value of the tower now might be very low, but the cultural value is quite high.”

While few chose a capsule as their full-time home, they have found a new lease of life as artist studios, quirky offices or storage units. And, as a one- night stopover, the Nakagin Tower offers a unique chance to sample Tokyo’s architectural history. Just make sure you pack light.

Solutions for crowded global cities – EG‘s The Next Big Thing competition is looking for exciting ideas for the future