The “registration gap”, the period of time between completion of a property disposition and the subsequent registration of the transaction at the Land Registry, is becoming an increasing problem, as it is taking longer to complete less straightforward registrations.

The “registration gap”, the period of time between completion of a property disposition and the subsequent registration of the transaction at the Land Registry, is becoming an increasing problem, as it is taking longer to complete less straightforward registrations.

Registration of leases can take up to seven months in some cases and landlords and tenants in particular can experience practical difficulties in exercising their rights pending registration.

The Land Registration Act 2002 (LRA 2002) paid little attention to this issue, because it was drafted on the assumption that electronic conveyancing (including simultaneous completion and registration) would be introduced shortly. In fact an electronic conveyancing system is now on the back burner. The registration gap is therefore one of the issues which the Law Commission has been asked to consider as part of its proposed review of land registration generally.

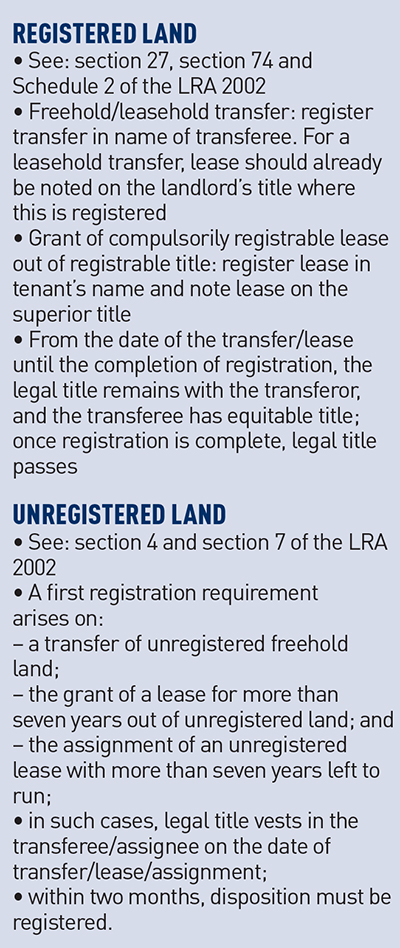

Legal position

In short, in relation to both freehold and leasehold registered land, legal title does not pass to the transferee until they are registered as proprietor at the Land Registry. The position in respect of unregistered land is different as legal title vests on completion, albeit that the disposition must be registered within two months, failing which the legal title will revert to the transferor. This causes practical problems, because certain rights can only be exercised by the legal (as opposed to the beneficial) owner.

Break notices

The first case that really highlighted the potential problems caused by the registration gap (albeit under the analogous provisions of the previous Land Registration Act of 1925) was Brown & Root Technology Ltd and anr v Sun Alliance and London Assurance Co [1997] 1 EGLR 39. In that case the original tenant purported to exercise a break right that was personal to it and fell away on assignment, despite the fact that it had assigned the lease to another group company with the landlord’s consent. The Court of Appeal held that as the assignment had never been registered it did not constitute a legal assignment and the break notice served by original tenant (who remained the legal tenant) was valid.

It appears to follow from the reasoning in Brown & Root that, at least in respect of “old” leases within the meaning of the Landlord and Tenant (Covenants) Act 1995 (LTCA 1995), a valid break notice can only be served by the registered parties. This can cause problems if the registration of a transfer of a lease is delayed and little time remains for exercise of the break right.

It has been considered that the decision in Brown & Root may well have been different if the lease in question was a “new” lease within the meaning of the LTCA 1995, because section 28 of that Act defines “assignment” as including an equitable assignment. Assuming therefore that a break right is a “landlord or tenant covenant” for the purposes of the 1995 Act (which seems likely in the light of the wide definition of covenant in section 28(1) of the Act) then it appears arguable that break notices served by or on landlords or tenants awaiting registration would be effective.

Subsequently, in addition to break notices, potential problems have been identified in respect of a landlord’s ability to forfeit a lease and the service of statutory notices during the registration gap.

Forfeiture proceedings

In relation to forfeiture, if a landlord wishes to forfeit a lease by court action it must serve a claim on the tenant. If there has been a recent assignment of the lease and the assignor remains the registered proprietor, it is advisable to serve the proceedings (and any prior notice pursuant to section 146 of the Law of Property Act 1925) on both the assignor and the assignee. The unregistered assignee would be entitled to apply for relief from forfeiture following the principle in High Street Investments Ltd v Bellshore Property Investments Ltd [1996] 2 EGLR 40.

It has, however, been held in the case of Scribes West Ltd v Relsa Anstalt (No 3) [2004] EWCA Civ 1744; [2005] 1 EGLR 22 that where the landlord’s reversionary interest has been recently transferred and the new but unregistered landlord seeks to forfeit a lease, this may occur in equity despite the fact the transferor retains legal title pending registration. Furthermore, in Rother District Investments Ltd v Corke [2004] EWHC 14 (Ch); [2004] 1 EGLR 47, a new but unregistered landlord was permitted to re-enter a property peaceably because, although there was no express authority, the High Court considered that the transferor had given the transferee implied authority to take action. In any event, in respect of “new” leases, section 4 of the LTCA 1995 expressly passes the benefit of the landlord’s rights of re-entry under a tenancy on an assignment (which is defined as including an equitable assignment).

Statutory notices

In Renshaw and others v Magnet Properties South East LLP [2008] 1 EGLR 42, the court held that a landlord’s counter notice served in collective enfranchisement proceedings pursuant to the Leasehold Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993 was invalid as the landlord had not yet been registered as the legal owner. It was the purchaser’s responsibility to safeguard its position by inserting a contractual term requiring the seller to serve the counter notice pending registration.

Similarly under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954, it has been held that references to “the landlord” are to the person in whom the legal title is vested and, in their text book Renewal of Business Tenancies, Reynolds & Clark express the view that, in respect of a registered lease, a new landlord awaiting registration cannot validly serve a section 25 notice. It seems to follow that a new tenant awaiting registration following an assignment cannot serve a section 26 request.

The difficulties caused by the registration gap relating to the service of statutory notices (as opposed to the exercise of rights under the lease itself) would appear to arise in respect of both “old” and “new” leases within the meaning of the LTCA 1995.

Practical steps

The growing registration gap is still causing problems. Careful consideration is required to identify the correct parties to serve and receive notices and appropriate drafting is required to mitigate the difficulties arising from delayed registration. Applications to register should be submitted as soon as possible after completion and the progress of the application monitored. In order to mitigate the problems caused by the registration gap it is prudent to include safeguard provisions in sale agreements, transfers, leases and assignments. With a formal consultation expected in spring 2016, and a draft bill in late 2017, it will be interesting to see whether the Law Commission seeks to address these issues in its review of land registration.

Safeguard provisions to consider

Acting for a buyer or tenant:

• An obligation from the seller/landlord not to exercise rights under leases or take steps in relation to the property between completion and registration.

• An obligation from the seller/landlord to pass on notices received.

• An obligation from the seller/landlord to take action at the buyer’s direction, eg if trying to grant leases to tenants pre-registration or intending to sell on during the gap (although, as the seller is simply holding the legal title on a bare trust for the buyer, it is considered that the seller should act as requested by the buyer in any event).

• A power of attorney from the seller in favour of the buyer to allow the buyer to take steps in the seller’s name, such as service of notices.

• An obligation on the seller to assist with remedying defects in the registration application (subject to an indemnity in favour of the seller).

Acting for a seller or landlord:

• If there are personal covenants or a personal break right, these should be expressed to terminate on the date of the assignment rather than the date the assignment is registered.

• “Old” leases: check that these require a covenant from any assignee to comply with the tenant covenants in the lease from the date of assignment, not the date of registration (this could also be dealt with in the licence to assign).

• “New” leases: under section 28 of the LTCA 1995, tenant covenants pass automatically on assignment, which includes equitable assignment. However, it is still not uncommon to include a direct covenant as for “old” leases.

• Licences to assign should include an obligation on the assignee to register the transfer.

• Licences to underlet should include a provision that the underlease should require the undertenant to register the underlease (if granted for a term exceeding seven years) and that any subsequent assignments be registered.

• Advise a seller or landlord that they will remain liable as the legal owner until the transfer is registered. They may wish to include an indemnity in the transfer/lease from the buyer/tenant or a contractual right to join the buyer/tenant in any actions.

David Stevens is a partner at Norton Rose Fulbright