Remember the summer of last year? As house-price inflation moved into double figures, the government was accused of stoking up an unsustainable pre-election boom, in part through its Help to Buy schemes for new homes and – subject to eligibility – the existing housing stock.

The Bank of England, while insisting its aim was not to control house prices, introduced a new 15% limit on the proportion any institution could have of mortgages advanced at 4.5 times or more of income.

In the end, fears of runaway house-price inflation proved to be unduly alarmist. Help to Buy, it seemed, had only a modest effect. Other factors, including mortgage availability, came into play, Mortgage approvals weakened a little. Panic over.

Or perhaps not. House-price inflation on most measures faded significantly from its double-figure peak in the autumn of last year; by the spring it was running at between 5% and 6% on the Office for National Statistics’ measure. Inflation in London faded particularly fast – and in prime central London prices fell – partly because of election uncertainty, and partly as a result of the stamp duty reforms unveiled by George Osborne last December.

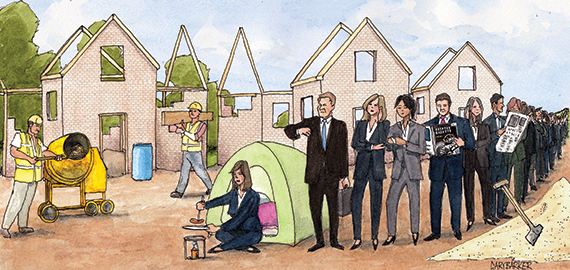

Now, however, the forces that pushed house prices up strongly last year appear to be returning. The latest RICS residential market survey suggests that the problem is low supply.

Stock per surveyor, a key measure of supply, has fallen to a record low of 47. A net 22% of surveyors in the latest survey, released in August, reported a drop in vendor instructions – the sixth successive month this has happened. According to RICS: “Respondents in all areas agree that the lack of property for sale is causing somewhat of a vicious cycle, as the limited choice on offer at present is deterring would-be movers and therefore further restricting new instructions.”

But the lack of supply is not being matched by weakness in demand. RICS reports that “national house price inflation accelerated for the sixth month in succession and has now reached a pace last seen back in July 2014”. Though that has yet to show through in the house-price indices, it very soon will.

This raises two important questions. The first is that, while the obsession among policymakers is increasing the supply of new housing, the supply of existing properties coming onto the market is at least as important, though it attracts rather less attention.

The second is the question of whether policy is inhibiting supply. The chancellor’s inheritance tax reform, with its new preferential tax treatment for “family homes” passed on to children, may persuade older people to stay in properties that are bigger than they need.

The other issue, of course, is the cost of moving. These days, with stamp duty and other costs, many people who do not have to move find it much more attractive to improve. Stamp duty used to be an inconvenience; now it is a major disincentive.

It should, of course, affect demand as well as supply. But what is happening is perfectly explicable: raise transaction costs and fewer people will transact. And there is no sign of that changing.

.

David Smith is economics editor at The Sunday Times