The number of shared office spaces in New York has exploded. But is the rapid growth sustainable or is the city now dangerously oversupplied? Jack Sidders reports

NEW YORK SPECIAL: Beer on tap; women-only offices; crafted congregation spaces to serve the creative ‘solopreneur’…

NEW YORK SPECIAL: Beer on tap; women-only offices; crafted congregation spaces to serve the creative ‘solopreneur’…

New York’s array of shared workspaces and the amenities they offer befits its reputation as the city that can satisfy any palate.

Serviced offices have boomed in every major city in recent years but, typically, New York’s explosion is on a different scale.

The city is the birthplace of WeWork – the $10bn (£7bn) start-up that operates from 52 locations, having launched in 2010 – and is home to more than 100 other co-working locations, from the corporate-friendly Regus to the invitation-only “series of experiences, spaces, amenities and opportunities suited to ambitious innovators” that is NeueHouse.

According to a league table compiled by New York real estate bible The Real Deal, the city’s top 15 shared space providers alone now span close to 5m sq ft – and that figure is growing weekly.

The big question is whether this new stock is necessary as an acute change in the way people work fuels a long-term need for serviced offices, or whether supply will soon outstrip demand.

After all, the city has seen a shared workspaces explosion before, in the run-up to the dotcom crash, when Regus filed for bankruptcy protection for its US business, having grown too quickly and committed to long leases.

So what does New York’s property industry make of this phenomenon? Are landlords comfortable leasing to businesses with little credit history, and are investors willing to buy up the buildings in which they are based?

Differentiating

The array of shared workspaces on offer in New York is overwhelming.

Local success stories such as Alley NYC – a start-up that launched in 2012 and raised $16m in its latest fundraising round earlier this year – are competing with international operators such as ServCorp, driving each provider to try to carve out its own niche.

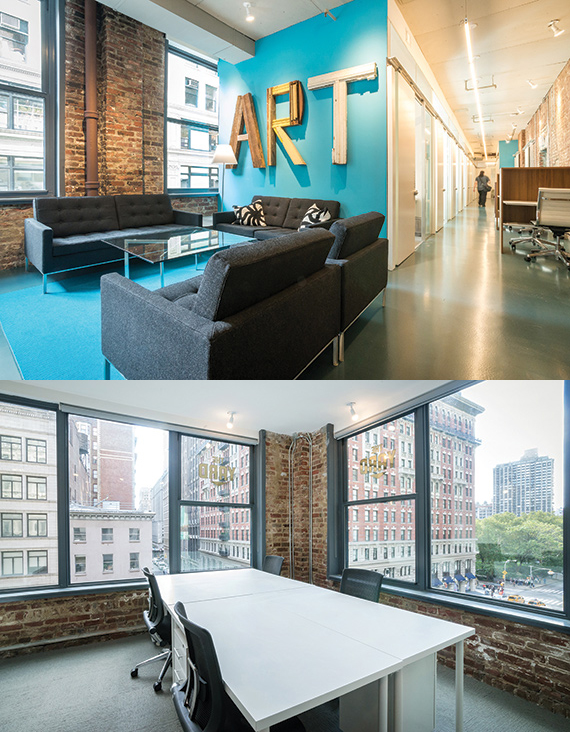

Andy Smith is director of operations, creative and business development at The Yard, which was founded in 2011 and now has four New York locations. “Now people know what co-working is all about, everyone is differentiating,” he says.

The Yard’s USP is its rotating exhibition of local artists. It services start-ups more than corporates, but makes a point of keeping its space respectable for the visiting clients of its users, avoiding WeWork’s free beer and “party atmosphere”, according to Smith.

He says the company is “significantly” oversubscribed, which has prompted it to lease three more locations that will open later this year.

“This idea of cubicles from nine to five is so outdated, but the alternative is still really new,” he says. “So right now we are in this really interesting shift in the way people work.”

But while the growth story is clear to see, not all are surviving in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

New Work City, a pioneer of the latest shared space explosion, closed its Broadway venue in June, and Makeshift Society will close its Brooklyn office in October.

Aaron Block, founder of real estate technology start-up accelerator programme MetaProp (see panel) believes there will be successes and failures among the dozens of new operators that have emerged. “There is a lot of garbage out there”, he says.

“It is pretty clear to me that there is enough room for high-quality operators of scale to expand, but there are more than 100 co-working companies out there – and that is not sustainable.”

Evolution of workspace

But Block agrees there is an irreversible “evolution of workspace happening” and adds: “The younger generation wants few strings attached and it is not going back the other way. The real estate community is certainly paying attention.”

WeWork has had investment from real estate grandees such as Boston Properties chairman Mort Zuckerman and Rudin Management chief executive William Rudin, and other big names are stalking the sector.

World Trade Center developer Silverstein Properties launched Silver Suites in 2012 to attract tech start-up companies looking for flexible space, while SL Green has its own shared-space provider called Emerge212.

Michael Colacino, president of Savills Studley, says landlords and large occupiers alike should take notice.

He is advising clients to make excess space available for flexible working, having spotted the opportunity that could flow from large corporates starting to make more use of shared spaces.

“The real source of demand is the flaking off of bits of space from major corporates for project work or new product launches,” says Colacino.

“The flaking of the crust where little pieces of traditional corporates are coming down into the shared office space –

how much of the overall corporate space in Manhattan is susceptible to that? 2%? 10%? That’s a 60m sq ft difference.”

But while many rush to cash in on the surge of interest in flexible working, not everyone is convinced, particularly if the shift towards traditional corporates using more shared space fails to materialise.

“I wouldn’t rent to WeWork,” says Anthony Malkin, chairman and chief executive of Empire State Realty Trust.

Before joining the family real estate business, Malkin worked in private equity and says he has concerns about the volume of private capital washing into these new companies and the valuations placed on them.

“WeWork is an aggregation of revenues from freelancers and small businesses generally in the realm of supporting high-growth companies and it doesn’t make sense to me to take a venture capital risk where your reward is that you get your rent paid,” he says.

However, it would be fair to say that while some sceptical voices persist, many, if not most landlords appear to have overcome concerns, demonstrated by the sheer volume of space being leased.

But what about investors? WeWork has only just begun its expansion in international markets and so the UK market has not yet seen how the firm’s covenant has affected the investment performance of the offices in which it is a tenant. But in the US there are now a few examples.

We Work is a major tenant at 175 Varick Street in Soho, New York, 51 Melcher Street and 745 Atlantic Avenue, both in Boston, and all have traded in the past year or so. The three buildings, priced at yields of 5.7% (August 2014), 5% (August 2014) and 4.9% (June 2015), were sold to blue-chip investors Tishman Speyer, Zurich North America and Oxford Properties, respectively.

For Guy Benn, a director at Savills Studley who looked at each of the deals for potential purchasers, there is little evidence that the covenant resulted in any discount, despite his own scepticism.

Grows from nothing

“I always get concerned when something grows from nothing to something enormous so quickly because it is a sign it is inflated,” he says. “But for investors who want to place money in core markets, it can be quite difficult to avoid a tenant like WeWork because they are in lots of buildings.”

The debate looks set to rage on, at least until there is a significant downturn, when some expect these operators to struggle, while others point out that this is traditionally when serviced offices perform best, as companies shed staff who often then set up small businesses.

But what ultimately happens at that point will have huge consequences for New York.

“It could be the best thing that has ever happened to this market – or the biggest bubble ever,” says Borja Sierra, Savills Studley executive managing director and head of US

capital markets.

Tech acceleration for real estate

New York’s first property technology accelerator programme, MetaProp, takes on its first cohort of start-ups this month.

Co-founder Aaron Block is on a mission to make sure the city doesn’t miss out on what he sees as its natural advantages to become the real estate tech capital of the world, building on local success stories such as WeWork.

The idea has the backing of heavyweight partners from the Real Estate Board of New York to the city’s Economic Development Corporation, all of whom share his ambition to unite the city’s tech, venture capital and real estate titans to help develop disruptive new products that will reshape the industry.

Block believes that real estate is “one of the last frontiers that is ripe for tech disruption”, lagging other industries such as finance, which have already established multiple technology accelerator spaces in New York.

“Even restaurant tech is ahead of real estate, despite being traditionally a ‘mom and pop’ industry,” he says.

MetaProp will invest about $5m in start-ups over the next few years, backed by partners including Warburg Realty, Zillow Group, DLA Piper, EisnerAmper and News Funnel.

jack.sidders@estatesgazette.com