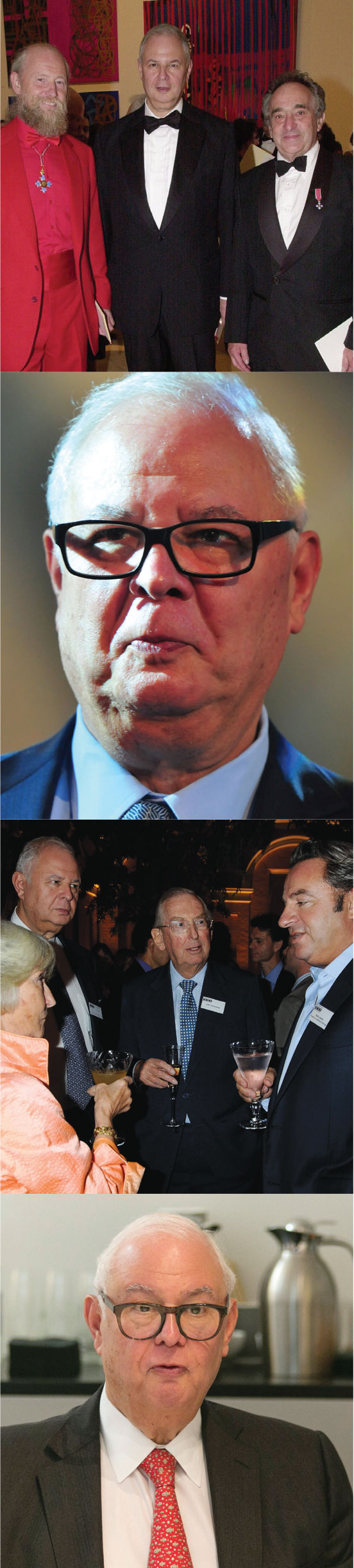

City planners this week gave Sir Stuart Lipton the go ahead to build the tallest skyscraper in the Square Mile. He talks to Damian Wild about the new thinking behind 22 Bishopsgate, government failures, and a rethink on Silvertown Quays

He may be into a fifth decade of changing the London skyline. His latest horizon-changing tower may just have won approval. And his ambition, evidenced by his plans for east London, may be undimmed. But don’t for a second think Sir Stuart Lipton is satisfied. A fire still burns brightly within him and his willingness to say the unsayable is perhaps unmatched.

He may be into a fifth decade of changing the London skyline. His latest horizon-changing tower may just have won approval. And his ambition, evidenced by his plans for east London, may be undimmed. But don’t for a second think Sir Stuart Lipton is satisfied. A fire still burns brightly within him and his willingness to say the unsayable is perhaps unmatched.

How many developers do you know who will admit to delivering buildings that have not stood the test of time? “There are ones I love, and ones I am disappointed in,” he says with surprising candour.

Try asking his peers to name publicly the local authorities they find it easy to work with and those that are more challenging, and you will mostly get short shrift. Not from Lipton.

“I think most local authorities want to be helpful but, in practice, if I wanted to see the leader of Camden tomorrow, I know who to call. But she’d first think, well he’s a Philistine developer. I might get in in a month’s time. If I wanted to see Mark Boleat tomorrow in the City, I would probably see him tomorrow. It’s just a different system where things get done. If only they ran the country.”

And his views on his own sector? Does he see an industry keeping up with the times; changing, adapting, improving?

“It’s probably worse now than it was,” he says. “If we look at how office buildings are built, Frank Lloyd Wright built a building for Johnson’s Wax in 1908. It is probably still the definitive office building. And if I look at my housebuilder friends, why didn’t they take notice of the Romans, who did a better job?

“We are in an industry where very little has changed. And yet we’ve got Airbnb and we work in Starbucks and we work at home and we live in the office. So, life has changed, but we are still in a system which is frozen.”

Pulling no punches, he draws an unflattering comparison with the auto industry. “If we put a building on a production line, a car production line, we would never reach the end. We couldn’t agree what it was going to look like or how it would be made. Half way down somebody would come along and change the regulations, and then we would find that there were parts missing. It’s a tremendous opportunity to change and to make housing, perhaps, into a product.”

Many readers will be nodding along with Lipton’s critique. But he’s no doomsayer, much less a fatalist.

This most decorated of developers – a knight of the realm, an honorary fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architecture and holder of honorary doctorates in both engineering and philosophy – celebrates his 73rd birthday this month. With a CV that boasts somewhere north of 20m sq ft of development in the capital – and in Broadgate, Stockley Park and Chiswick Park three genuine game-changers – he could quite easily rest on his laurels.

He is not resting, of course. Instead he is focused on two projects that could be every bit as disruptive, not least in his commitment to put people first.

“Office buildings are the servants of individuals, not of corporates,” he says – a philosophy he is pursuing at 22 Bishopsgate, EC2, the 62-storey tower that will rise from the ashes of the Pinnacle in the City of London in 2019.

Developed by Lipton Rogers with AXA Investment Managers – Real Assets, it will be the first UK building to adopt the Delos WELL Building Standard. Better known in the US, the standard covers everything from light to fitness to nutrition.

For Lipton, it is a different and necessary way of looking at buildings. “It means the building has to be tested for air quality, water, materials and amenities – things you might personally find of benefit. Whereas BREAM is about the government’s energy codes and materials, and not really about ‘you’. Perhaps ‘you’ are more important. But the government doesn’t think that. We are trying to treat people as individuals.”

He credits Kay Chaston with changing his thinking. Chaston joined Stanhope in 2001 as chief executive of Chiswick Park from roles in North America’s premium hotel industry.

She and Lipton – with Peter Rogers, his Stanhope co-founder – together delivered Chiswick Park. “I learnt a lot from Kay. She didn’t talk about tenants, she talked about guests. At Chiswick you go in and somebody actually gives you a smile. It’s a security guy, but he’s in a yellow blouson, and at lunch time they might give you an ice cream or a cold drink. They might treat you like a person.”

It is a philosophy that will be applied at 22 Bishopsgate.

It is a philosophy that will be applied at 22 Bishopsgate.

“Life and business and social and home is all merging. People work mad hours. Their commitment is terrific. They need a contrast, a contrast to the screen, a contrast to their workplace.

“Go to Australia or the Netherlands and you see completely different styles. People are not working in pens. They are sitting on sofas; they are at bars. They are in a whole variety of spaces. And in Australia they are working in groups. You feel the work ethic. Go around a UK building, people are looking bored.”

For Lipton, the government’s inability to deliver buildings designed for people is matched by its failure to deal with the housing crisis.

“Buildings are about life, governments are about death,” he says. “It’s our job to try to tease government, who should be the leaders, and local government, who run the rules, to try and think of humanity.”

If Lipton has high hopes that 22 Bishopsgate will reinvent the tower, he believes his other major project, Silvertown Quays, will transform a 60-acre site in east London. The Silvertown Partnership comprises investment bank Macquarie Capital, Lipton’s Chelsfield and First Base, the mixed-use developer run by his son, Elliot.

“A new piece of city is very difficult to find,” says Lipton. “Go to Soho; that’s a great piece of city. Go to downtown New York or downtown San Francisco, those are pieces of cities most people like. So the goal is to try to produce a new Soho: interesting buildings, interesting spaces and buildings really for makers. Virtually everything we do now is by makers, Google is a maker of one description and Ferrari is a maker by another description. Silvertown is for people who make things and can show them. Make and show and tell.”

With 22 Bishopsgate approved by the City of London’s planning committee this week, Silvertown might now require more of his attention. It had been expected to deliver up to 3,000 homes, 2m sq ft of commercial space and 3m sq ft of brand space. But it sounds like the latter component is being rethought – at least presentationally.

“I think we got the word ‘brand’ wrong,” he admits. “People don’t understand what brands are. Chances are everyone today has used a brand for something or other. My razor is a brand. My toothbrush is a brand. My soap is a brand. My suit is a brand. There’s not much which isn’t connected to brands, but it’s not a familiar name, so I think we got that wrong. But ‘makers’ most people understand.”

So a rebranding of sorts beckons for Silvertown, including a new name. Can these next two developments be as game-changing as those served up by Lipton in the past? Don’t bet against it.

damian.wild@estatesgazette.com