What would happen if we built 2m homes by the end of 2016?

What would happen if we built 2m homes by the end of 2016?

Aside from bankrupting the house builders fairly quickly, we might also upset the vast majority of the property-owning population – particularly those using their homes, or their buy-to-let properties, as their pension pots.

The subsequent fall in house prices could also leave bankers in a pickle, ruining their recovering balance books, which in turn could derail the UK’s economic growth and possibly plunge the country back into recession.

Meanwhile, the political landscape might see a huge swing towards Labour as the Conservatives alienate the vast majority of their voters by evaporating the value of their investments.

Hands up, this is clearly a worst-case scenario for a ridiculous question. It is a situation the UK will never find itself in. But it illustrates that although solving the housing crisis is top of the national agenda, it needs solving in the right way. Because, actually, satisfying demand in one go is no longer in the interests of a large part of the population.

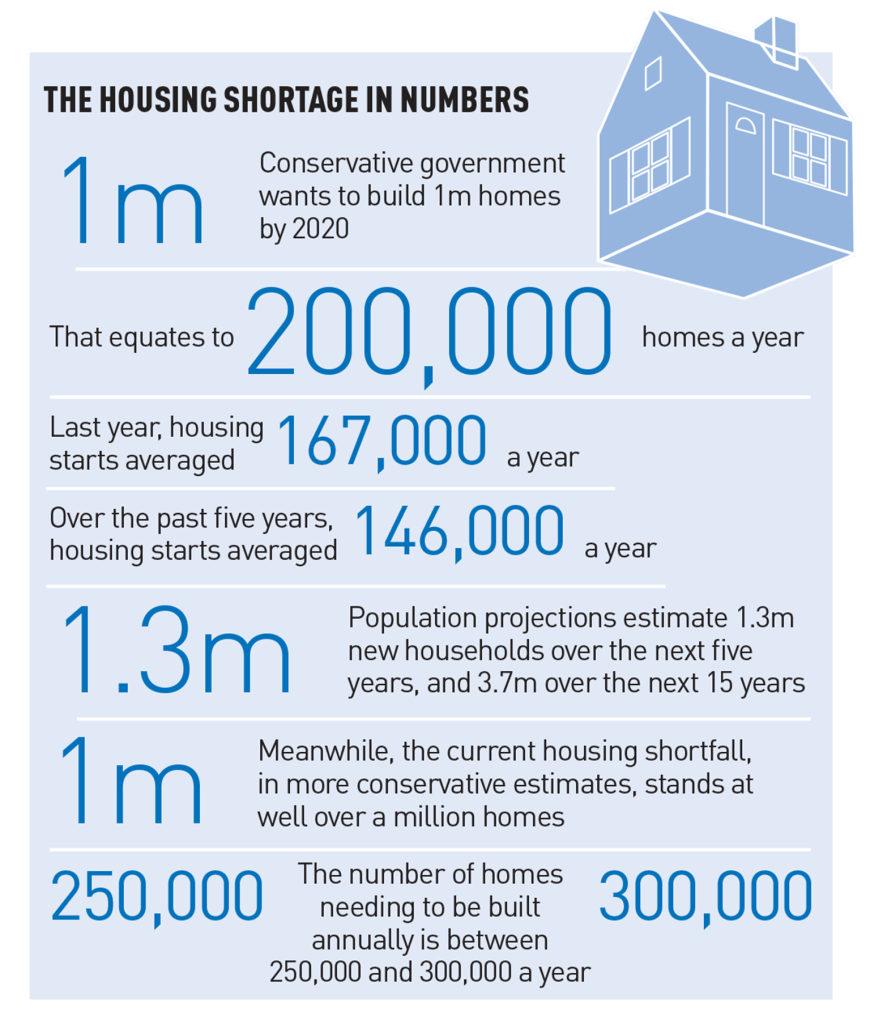

The UK is estimated to need 250,000 homes a year. The Conservatives have pledged to build 1m by 2020. The current shortfall in homes is estimated to stand at more than 1m.

Technically, by building 2m, all we would be doing is meeting demand. Realistically, the effects would be more severe.

GCSE economics

It comes down to supply and demand. If you flood a market, prices fall. Though we need at least 2m homes, the UK cannot absorb them all at once.

The problem, explains Richard Donnell, research director and insight at Hometrack, is that years of undersupply have changed a market in which housing is good for consumption into one that is investment-led, and puts pressure on prices.

So, if 2m were built, and built for sale, what would happen? “They would have to be priced to sell,” says Donnell. “That would flood the market, as that’s double the number of annual turnover, and house prices would re-set themselves.”

“In terms of that scale,” says Neal Hudson, associate director of residential research at Savills, “it would be destructive to the UK economy, as a massive amount of bank lending is secured against homes. With that much supply, prices would fall, and that would wipe out value. People would go into negative equity.”

After years of undersupply, the UK economy and house building sector have moved beyond being able to cope with such a shock.

Where? And what type?

Where these houses were built would also affect the market’s ability to cope. In many parts of the UK, prices are still well below their pre-recession peak. Further boosting supply would drive down prices and possibly lead to more negative equity.

Falling prices would also stop people from moving into the new homes, as they would not be able to sell their current ones.

Samuel Blake, director of development consulting and agency at BNP Paribas Real Estate, says: “[A falling market] traps people because they cannot move and cannot re-mortgage. And that’s still the case in many parts of the North, where house prices have not fully recovered.”

Even in the South East, where demand for housing and population pressures have pushed prices up by 25% in the past five years, a supply glut would cause problems. Price growth, in London especially, is now starting to cool as the market reaches the limits of affordability.

Rates of absorption vary across the UK. “Depending on where they were distributed, an awful lot of places could not cope with too many houses at one time. They would just sit on the market,” says Blake.

Even house builders in London carefully moderate completions on major schemes. A supply glut would upset pricing projections and absorption rates.

“The question is, are there really 2m people who would want to buy a new home?” says Donnell.

A mixture of tenures could help assimilation to an extent. Supplying both private rented stock and social housing would increase absorption rates.

“If it was just 2m homes for sale, you would have a supply far in excess of demand and prices would fall. If they were in social and rented tenures, then occupation would be less of an issue, and that would go a long way towards absorbing them,” says Hudson.

But even then, there would be immediate issues created.

Jason Hardman, senior director of CBRE valuation and advisory services, says: “If some of the homes are going to be rented, tenants are going to live only where there are jobs.”

Meanwhile, more rented and social housing would have a knock-on effect on the build-for-sale market. Thousands not eligible for social housing would instead join the housing waiting list. If the homes were built for private rent, rents could go down, allowing people to rent for longer.

“Some proportion of those seeking to buy with no access to affordable housing would then have access to it, which would have a knock-on effect on house prices,” says Hardman.

How would it be supported?

And all this is presuming the UK’s creaking infrastructure could support such an influx of new homes, not to mention the issue of how they could be built within that time scale.

“Fine, pop, 2m houses down, but how are we going to support these people in terms of basic services?” asks Walter Boettcher, director of research and forecasting at Colliers International.

“Look at energy supplies. We do not have the transmissions capacity. It would pose a huge infrastructural problem.”

Two million houses, of various tenures and sizes, if all built in one place, would create the UK’s second-largest city. Such a metropolis would need roads, schools, waste disposal, transport, shops and jobs.

“The houses would have to be in the right place, but the infrastructure would have to be in the right place too,” says Hardman. “If you did not have that, it would be a disaster.

Likewise, the legal and banking sectors would be far from able to cope (see box out).

“It would cause a massive problem for lenders,” says Donnell. “It would mean turning over 2m loan applications in a year, which we have not done since 1988.”

But in the long run?

But getting past the initial shock to the system and possible recession, would the houses be absorbed in the long term?

“The question that comes to my mind is, will there still be a shortage after 2m are built?” says Boettcher.

“I would suggest it would be a stopgap measure. If you look at population growth over the next 15 years, the number of homes needed is far higher.”

Recent forecasts from the ONS say there will be a further 1.3m households by 2020. By 2030, the population of the UK is set to rise to 71.4m, with 3.7m households, an increase of 13.6%.

In the grand scale of things, 2m homes is not a big number, and could be easily absorbed. A fall in house prices would help much of “generation rent” get on the first rung of the housing ladders and out of their parents’ homes.

“In the year or two following delivery, some homeowners would feel the effect on house prices, and this would have a knock-on effect on those with mortgages,” says Grainne Gilmore, head of residential research at Knight Frank.

“The other side of this coin, however, is that those struggling to buy a home could find the first rung of the housing ladder within closer reach. Assuming mortgage lenders have not had to adjust their business models, the generation effect of wealth could be partly reversed.”

The solution?

But in the short term, with housing treated as an investment by so many, the economic effects would be severe. A solution to the housing crisis cannot just be a glut of supply. What the market needs, according to Simon Rubinsohn, chief economist at the RICS, is a return to more normal house price growth that is outpaced by wage increases.

Rubinsohn says: “The bigger issue here is how to get to the point at which you have a more affordable housing market, how you move to a situation in which prices are not falling, but move with inflation, while in real terms people’s earning power is growing faster.

“The government is grappling with this, providing some discounted properties, and greater subsidies for those in the London area.”

Hudson agrees, saying: “One of the solutions is not building more houses, it’s about providing attractive alternative investments for people to put their pensions into.”

“None of this is to say we don’t need more houses – we definitely do,” adds Gilmore, “but the economy is unlikely to be best served by supply vastly outstripping demand in one lump. From where we are now, meeting annual demand for housing is crucial.”

Building 2m homes in a year is a ridiculous notion. But it serves to illustrate the point that just blindly increasing supply could cause more problems than it solves.