It is no exaggeration to claim that much of what affects us daily in relation to the public sector is managed at the local authority level. However, while the majority of tax revenues are raised locally, these are then channelled into a vast tax vat based in London, then dispersed back from where they came, alms-like, and hardly ever pari passu.

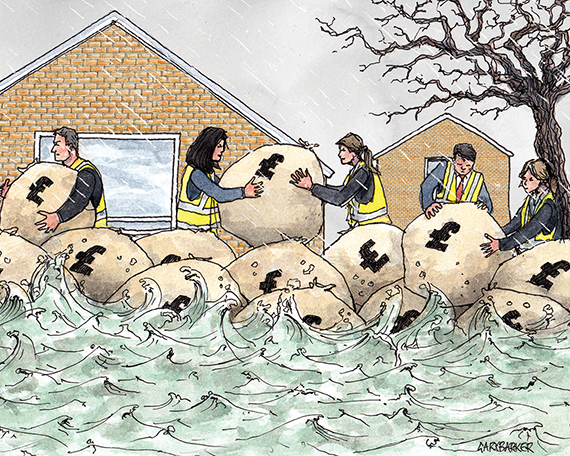

Consider the recent seemingly interminable rain which so badly affected parts of the UK. These downpours were meteorological and climatic in origin, not economic or political. This said, the discussion and controversy surrounding the preparedness of the areas so dramatically affected, and how flood ‘defences’ were funded, turned on these latter themes.

Imagine if local authorities in flood-risk areas were empowered to levy taxes on households and businesses, the receipts from which were hypothecated to be used for flood defences. Let me ask two questions. First, would locals have been willing, and second, would preparedness have been much improved as a result? I am convinced the answer to both questions would be yes.

Some will argue that it should not be left to those who face such threats to confront them alone – that all those in the UK should share a fiscal responsibility. After all, those unaffected this time by floods may face their own challenges in the future. And no doubt they would expect the cost burden of dealing with their misfortunes to be shared by their fellow nationals.

Consider the Thames Barrier. This has provided flood defences for London since 1983. It cost the UK exchequer £1.6bn in current prices and was funded by many taxpayers with no pecuniary interest in the area it was designed to protect. But far from making this a precedent to follow, it is a case study in why funding for regionally specific ventures needs to be done differently. Indeed, there is talk of a Thames Barrier 2. Given the sheer scale of the property wealth which a prospective second barrier would be protecting, surely taxpayers across London cannot object to paying.

There was a longstanding need for the Thames Barrier, London having been particularly badly inundated by flood waters in 1928, 1947, 1953 and 1968. As remarkable an engineering achievement as the Thames Barrier is, it is no less remarkable that it took such a long time for something to be put in place to protect us and our property; allowing more favourable insurance premiums and avoiding the incalculable costs incurred from business disruption and household relocation.

Of course we have council tax and non-domestic rates, which provide some discretion for localised tax gathering and spending. My argument is that the flexibility of both falls short of what is needed. They do not, for example, have the discretion for hypothecated taxation to deal with region-specific issues as flood defences. We also need an ‘intelligent’ approach such that properties are rated in a more timely way, and for business premises to be valued according to the audited annual incomes they help generate.

Savvas Savouri is chief economist, Toscafund