Kris Gumbrell, head of the UK’s largest micro-brewing chain, reveals his ambitious expansion plans, the benefits of the brewpub world, and the pitfalls of the burgeoning sector

When the UK’s largest micro-brewery chain consists of just nine pubs, it shows just how micro the market actually is. The sector is flooded with one-off operations and one-man brewing businesses.

This individualism makes it difficult to know how many of the UK’s 1,258 registered breweries they comprise, but what they lack in big chains, they make up for in success, as last year’s drinking statistics prove. Ale and bitter consumption among the British public jumped from 895m litres in 2014 to 913m litres in 2015, according to market analyst Mintel.

It is in this market that Kris Gumbrell, chairman of that nine-strong chain, Brewhouse & Kitchen, wants to have greater presence.

Sitting in B&K Highbury, N5, formerly The Junction, Gumbrell is talking openly about his company, which has been operating for three years, its extensive UK and international expansion plans, how he got into the market, and his thoughts on the brewpub and micro-brewery sector.

In transforming The Junction, a football-oriented boozer that Gumbrell bought in August 2014, he created the template for his pubs: decor of wood, brass and subtle lighting for the interior, with the pièce de résistance – the brewery – on full display at towards the back of the room.

Customers clearly like what they see – and drink. In the final quarter of 2015, B&K saw like-for-like growth of 17% in its uninvested estate and 79% in its invested estate.

While the emphasis is on beer – own-brewed volumes are between 40% and 60% of all draught sales – food is also hugely popular. In the same quarter, sales grew from 32% to 36% across all nine pubs. “In monetary terms, this accounts for between £20,000 and £25,000 per week net of VAT,” says Gumbrell.

Popularity and the US influence

The popularity of micro-breweries – generally defined as small breweries producing less than 5,000 litres of beer per year – has grown “because people want a product that they can get more engaged in”, says Gumbrel. “They get closer to the process. They want a stronger product with more flavour and they want to identify with the locality of what is brewed.”

Pubs have always been in Gumbrell’s blood. His parents worked in the licensing trade and he was “collecting glasses from 10 years old”. Then straight from college in 1988, he started working for Bass. “I have probably held nearly every conceivable operational job in the industry,” he says.

It was working for Scottish & Newcastle’s international development team, where Gumbrell was building pubs and bars in foreign markets, that he first started to see how successful brewpubs were, particularly in the US.

Gumbrell cites US chains such as BJ’s Restaurant & Brewhouse, founded in 1978, with 171 restaurants, and McMenamin’s, founded in 1983, with 65 outlets, as perfect examples of how the Americans are getting it right.

“The US is a really good example of how the casual dining and pub model is fused together much better than what we have seen in the UK… US brewpubs were brave enough to create beer brands around their local guests. It was a great idea, and why not?”

His time running Convivial London Pubs convinced Gumbrell that the micro-brewing industry could take off again in the 21st century. “We sold the company in 2013, but I had two unbranded microbrewery business in CLP, and I saw the massive and positive effect they had on trading.

“It improved the profile of the customers. It drove up the spend per head. It lifted the actual sales and revenue. It allowed us to take other decisions in the business.”

History and failure

History and failure

Of course, micro-brewing is not new. It originated as a cottage industry and in the 19th century most inns and taverns brewed their own beer.

A modern-day version began in the early 1970s, and the Firkin Brewery – opened in 1979 – became the UK’s biggest brewpub chain before being wound up in 2001. But the dominance of the large and medium-sized brewers over the past 30 years resulted in little incentive or access to sites where in-house brewing could occur.

Things started to change for the sector when the micro-brewing industry had a helping hand from the government. Chris Wisson, senior drinks analyst at Mintel, says it was the implementation of the small breweries relief/progressive beer duty in 2002 that was “undoubtedly at the heart of the growth of craft beer”.

He says: “The smallest beer producers can pay as much as 50% less tax than larger brewers and this has provided the platform for a significant number of new breweries to form and build momentum, so much so that the UK now has the highest number of breweries per head in the world.”

New breweries continue to spring up on a weekly basis, says Wisson. “There appears to be no immediate end to this spike in new brewery numbers.

“However, there may also be a degree of churn, with some breweries going out of business as retail spaces remain highly competitive and the number of pubs continues to fall.”

Cost is clearly an issue for operators, and setting up a micro-brewery does not come cheap. On the brewery alone, Gumbrell says, “You could spend anything from £30,000 upwards.”

The property issue

Then there is the property cost if the brewer wants to sell its own beer. B&K looks for units of around 3,500 sq ft for the brewery and 100 covers internally. External covers are preferred, in a town centre or on the edge of a town centre, in what Gumbrell calls “a good neighbourhood with reasonably decent footfall”.

As for the type of B&K building, anything goes: Grade II listed traditional pubs; concrete boxes; converted old tram sheds; the ground floor of office blocks and new-build. “For us, it is what’s inside the building, and the brewery is quite an adaptable model.”

But Gumbrell is a stickler for freehold properties. They are, he says, easy to borrow against.

“We have got the cash because we are an EIS [Enterprise Investment Scheme] backed company, so we are a cash buyer generally.”

He adds: “You create heritable value, with a freehold – you are more attractive to trade buyers on exit. We can leverage against those freeholds more easily and in time we still have the option and the opportunity to come out of those freeholds and sell them on as investments once you have established the trade on our terms.”

Launched in 1994, EIS is a series of UK tax reliefs to encourage investment in small unquoted companies.

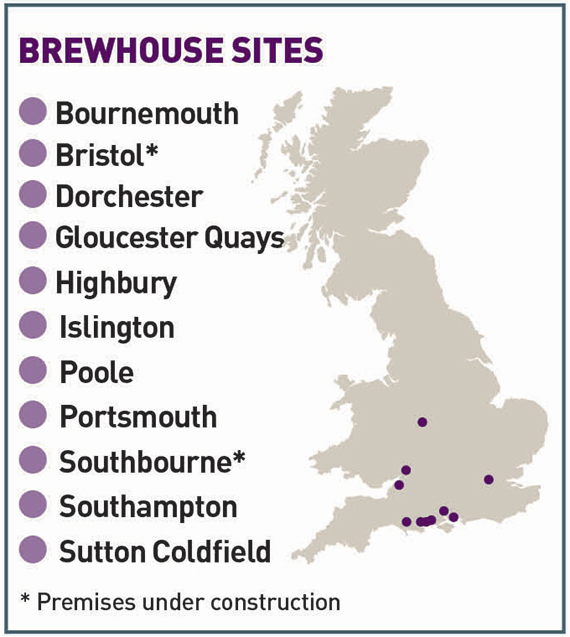

Working with London-based agency Fleurets, among others, Gumbrell intends to add two more pubs to his current nine by April, with a target total of up to 18 by the end of the year. He is looking in Manchester and Nottingham, and in time B&K will branch out into Scotland and Wales. Central London is out, however, because of what Gumbrell calls commercially unviable, overpriced “showcases leases”.

Why look to add so many new pubs in 2016? Gumbrell says: “We have got to achieve in the first six months of this year the same level of growth we have achieved in the entirety of last year… It is just the momentum. We seem to be quite attractive at the moment in that we are still cash buyers, which means we transact quickly and cleanly.”

Taking a cautious approach

However, Gumbrell is cautious that B&K does not to grow too fast. “We need to slow it right down for the following year because, with having a foot in the casual dining space and a foot in the pub space, both camps are very competitive.”

Slowing down in 2017, however, does not mean standing still. Gumbrell’s five-year plan is that there will eventually be 30 B&Ks, with the international market in his sights.

“We have had another growth spurt this year. At some point, we want to consolidate and focus on execution. We are not bad at what we do, but we have got a lot of work to do once we stabilise.”

Gumbrell says he has had “expressions” for B&K to open abroad. “Europe is an area in which we have had interest. We have had interest in the past from Asia. But that is not of interest for us right now. We want to focus on the home market, domestic market and build a really strong business.”

For now, at least, it seems the thirst of the British beer drinker will be keeping that market strong for a while to come.