The northern powerhouse has been hailed as the most powerful reason to invest in England’s Northern cities since the 1940s. Promoted by chancellor of the exchequer George Osborne and supported enthusiastically by mayors and local leaders across the North of England, it is already said to be boosting the property market.

If it works, it will produce an investment opportunity on a global scale. Already there are claims that yields are hardening, and developers developing, because of it.

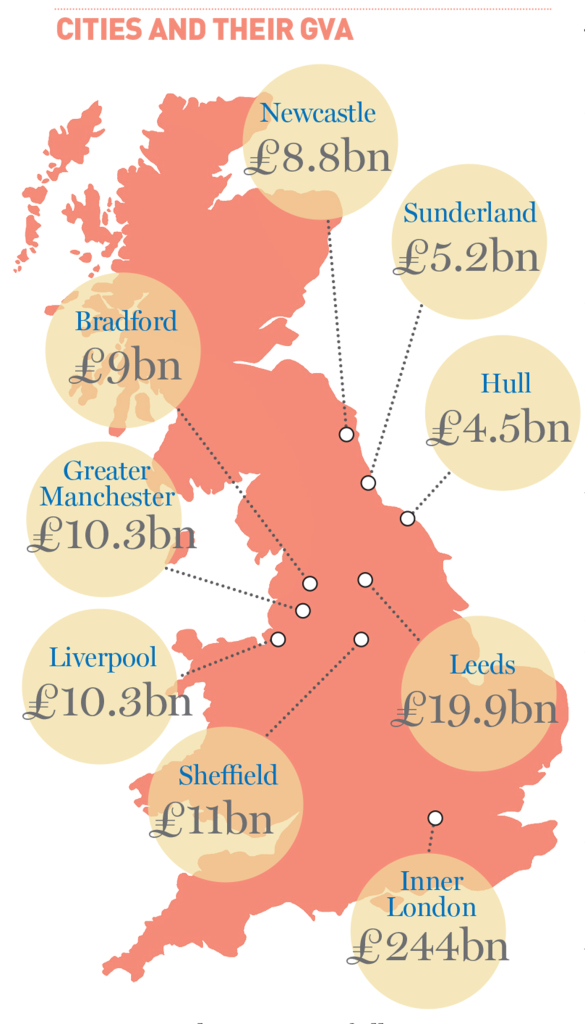

Yet behind the excitement and good intentions lurks a series of tricky and as yet unanswered, questions. Will the government really come up with the cash the project needs (see p21)? Will the half-dozen major cities involved – Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Hull and Newcastle – really co-operate? Above all, what does the northern powerhouse mean? Answering the last question ought to be the easy, but it turns out to be the hardest. The answer will determine whether the northern powerhouse is just a here-today-gone-tomorrow slogan, or an investment and growth package with international appeal.

Yet behind the excitement and good intentions lurks a series of tricky and as yet unanswered, questions. Will the government really come up with the cash the project needs (see p21)? Will the half-dozen major cities involved – Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Hull and Newcastle – really co-operate? Above all, what does the northern powerhouse mean? Answering the last question ought to be the easy, but it turns out to be the hardest. The answer will determine whether the northern powerhouse is just a here-today-gone-tomorrow slogan, or an investment and growth package with international appeal.

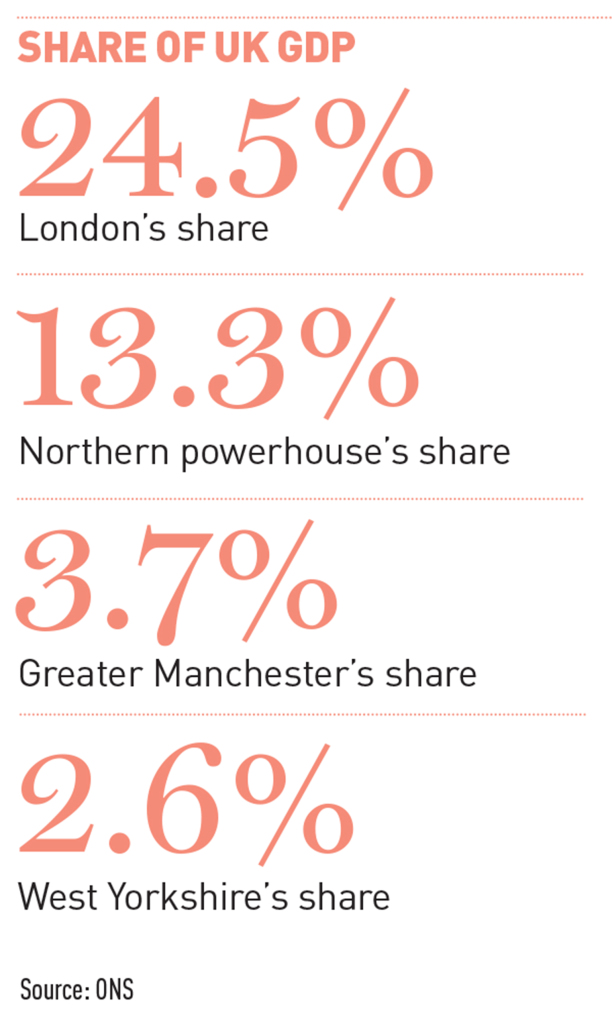

The official answer is that the UK economy is too reliant on London, and needs to be rebalanced (see box, overleaf). So the UK government aims to match the South’s economic powerhouse based on London with a northern powerhouse based on… . And that’s where the problems begin.

A popular answer is to suggest the northern powerhouse won’t be based on any one city, but will be a together-we-are-stronger agglomeration of all six cities. It could work in the same way as other European city clusters, like Germany’s Ruhr region, or the Dutch Randstad.

Chris Perkins is head of business space at M&G Real Estate, one of the biggest investors in the North, spending around £500m in the past 12 months on sites and developments in Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds. Perkins says: “I’m looking to the example of the Randstad. The North could emulate Amsterdam, the Hague, Rotterdam, Utrecht, all of which have their own strengths and equal weighting.”

Chris Taylor, chief executive at Hermes Real Estates and another big investor in the Northern cities, takes a similar view. “Look at the Ruhr, which is an equivalent area with a number of industrial cities that have suffered structural economic decline and have had to re-invent themselves. Dortmund, Essen, Düsseldorf – they work together, and the key has been infrastructure to link the cities together.”

The difficulty with comparing the north of England to the Ruhr or Randstad is that unlike the Ruhr or the Randstad, the cities of Northern England are not of roughly equal size and strength. Greater Manchester is – on some measures – the largest, and it has the best-developed local political structure. It is also on the doorstep of Cheshire MP, and chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne. Fairly or unfairly, it has dominated the debate.

According to the Manchester Office Agents Forum, in 2015 Manchester’s combined city centre, business parks and quayside office market take-up totalled 2.5m sq ft. This was an impressive 30% up on 2014 and roughly the same as the all the other Northern cities’ occupational markets added together.

Imagining that the other cities can work with Manchester as equals is an obviously crazy idea in the mind of some observers – most, not all of them, in Manchester. They say other cities have a lot of catching up to do, such as developing their economic strategy, and their political leadership. One senior property investment broker in Leeds says: “Manchester is the dominant centre by a country mile, a proper grown-up city.”

Such is the strength of local Yorkshire pride that the broker insisted on anonymity. With local loyalties still strong, getting the cities to work together will not be easy.

Mark Rawstron is regional senior director at Bilfinger GVA and the channel for much of the high volume of German and Swiss investment that reaches the North of England. He says that the greater economic and political strength of Manchester means it will dominate the northern powerhouse to start with – but in the longer term, as the Northern economy improves and other cities grow, a more equal Ruhr/Randstad arrangement will develop.

“At present we have to think of the northern powerhouse on a hub-and-spoke model, with Manchester as the hub, and that’s because Manchester has the political, civic and economic infrastructure. It is years ahead of the other cities in developing that infrastructure, and the other cities need to play catch up. But each city has unique strengths and in time they will develop their capacities in a way that Manchester has already,” says Rawstron. These areas of strength will be provide the main property investment opportunities.

It is not yet clear whether Manchester will dominate a spoke-and-hub version of the northern powerhouse in the same way that London dominates the “southern powerhouse”. Nor is it clear whether the other Northern cities can develop the strong political leadership that a more equal Randstad/Ruhr model would need.

City devolution

Devolution of power from Westminster to the city regions of the northern powerhouse is now underway. The agreements, now being negotiated and extended, could produce powerful city-states that could be engines for growth.

Manchester has had city-wide devolution, through a regional tier of government called a combined authority, since 2011. However, devolution deals in the other cities are in their early days, starting in 2014 in Liverpool, North East/Newcastle, Leeds and Sheffield. Most have yet to acquire the full range of powers handed to Manchester.

Data from think tank CEBR shows that 60% of people in Manchester and Liverpool – but only 45% in Sheffield and Leeds, and a modest 31% around Newcastle – think devolution will help stimulate their economies.

John Harcourt, head of Kajima Properties, the UK arm of Japan’s Kajima Corporation, says newcomers will find plenty of opportunities in the North. Kajima is already backing a 200,000 sq ft retail redevelopment in Rochdale, Greater Manchester.

“The new city devolution deals in Manchester and other northern powerhouse cities are going to provide great opportunities and will drive investment,” he says.

Harcourt adds that the deals could stimulate more local development partnerships with the public sector.

“Giving areas more control over their destiny will create opportunities,” he says.