You can’t turn around in Manchester these days without walking into a potential skyscraper development site.

You can’t turn around in Manchester these days without walking into a potential skyscraper development site.

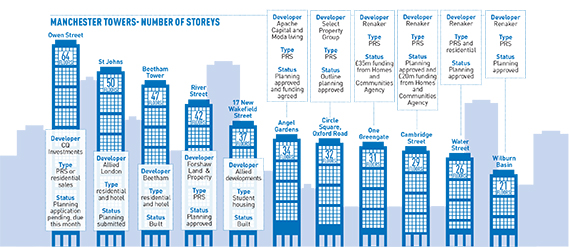

Just a few weeks ago, Apache Capital put up the money for the £128m Angel Gardens scheme in the city’s northern fringe, a joint venture with Moda Living. The 34-storey private rented sector (PRS) scheme joins a long list of plans in various stages (see p115).

Yet Manchester has a patchy history of tower development. The last boom delivered just one genuine skyscraper, the 47-storey Beetham Tower – and its developer, Regional Landmark Hotels, previously Beetham Organisation, later went into administration. The recession unexpectedly delivered a second: the 37-storey tower at 17 New Wakefield Street, a student housing scheme by Allied Developments. Skyscraper plans provide great publicity for architects, help developers to persuade city planners of their go-getting civic ambition, and mostly end up in the bin.

Today, with some developers and some locations untested, construction costs rising and land prices soaring to £4m-£5m an acre in city fringe locations, the question on many observers’ minds is: will any of them get built?

According to Steven Verity, senior director at CBRE, most are punts, not plans. “There’s a lot of talk, most will never get built – perhaps 30% will,” he says. “Today, for a few hundred thousand pounds, you can put a scheme round the market with planning permission, and there are potentially big rewards if it works.”

As in any gold rush, day-trippers from London with big ideas, and locals with a dream, are beginning to make themselves felt. “They are starting to appear in the wine bars… along with the hardy perennials who are always trying to develop and are popping up again hoping for another try, all with the same old story of jam tomorrow,” said one jaundiced observer.

“The last time we saw so much activity was in 2008 just before the crash, when getting debt was, unhelpfully, a walk in the park,” says Ken Knott, chief development officer at Select Property Group. “Today that’s not the case and lenders are rightly much more cautious, so the schemes being proposed in marginal locations may struggle to get funding. My guess would be that only those developments in prime locations are likely to get built out.”

Knott – who is presiding over a 32-storey tower at Circle Square, Oxford Road, and 36 storeys at the Embankment – thinks this caution applies even more powerfully to tall towers. “The financial equation of a skyscraper is very demanding. Realistically that is only going to happen in prime locations,” he says.

Phil Mayall, development director at Muse Developments, has a 90-unit PRS scheme at New Bailey under construction and is unveiling another 135-unit scheme this week. He says hard commercial realities eventually undermine the less-serious proposals.

“Rising construction costs are a natural brake,” he says. There are said to be just three or four contractors capable of taking on Manchester’s high-rise schemes – and finding the right subcontractors is harder still (see p113).

Manchester Place – an initiative run by Manchester City Council with funding from the Homes and Communities Agency – is regarded as one of the safest ways to make certain that deserving plans get delivered.

Paul Beardmore, Manchester City Council’s director of housing, is overseeing the scheme, which identifies areas for private sector investment and works with land owners, developers and investors to bring schemes forward. That includes providing money from a revolving fund, and acting as broker, bringing together investors looking for assets with developers looking for exits.

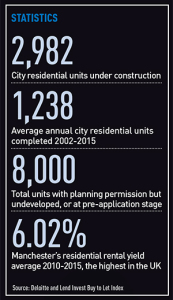

Under the system, 3,908 units in 40 schemes are already under construction, including six large central Manchester projects.

Beardmore says the aim is to stimulate good projects, stop poor-quality towers – and avoid some of the problems of neglect associated with predominantly buy-to-let owned blocks.

“If developers come forward with a cheap-and-cheerful plan to get planning permission, I’m confident we can stop that happening. We feel we have kept a tight lid on quality,” Beardmore insists, saying Manchester applies the same housing space requirements adopted in London, and they encourage developers and buy-to-let investors to form unified management companies that handle all tenancy issues. “We have learned lessons,” he says of the chaotic arrangements of blocks with dozens of landlords and no overall control.

Robert Hogarth, associate director at JLL, says construction costs will dent the profitability of many schemes, but developers and funders will go ahead anyway. “There’s such a sense of optimism, they want to capitalise on the market,” he adds. “Maybe the returns will not be as good as they thought, but skyscrapers will be a significant feature of the city from now on.”

Is Manchester ready for towers?

Manchester must learn fast if it is to cope with the rash of skyscraper plans. So says Sam Wallis, head of the new Manchester office of GIA. The firm has advised on a host of London’s skyscrapers, including the Shard.

“In London you have protected views and vistas, and you look regularly at how solar glare affects bus and train or tram drivers – but not in Manchester. We’ve maybe done three assessments in eight years in Manchester,” he says.

“The city needs to make sure these big buildings interact with each other, which means issues such as daylight and overshadowing need to be part of the planning process,” he says.

Getting it out of the ground

Construction costs can quickly endanger viability in today’s Manchester market, says Damian Flood, the man behind Real Estate Development’s plans for 470 units in towers of 24 and 17 storeys at No 1 Old Trafford. His build costs are £180-£200 per sq ft.

“Appraisals have to take into account things like basement car parking, because in Manchester selling the spaces at £10,000-£15,000 each won’t get you your money back,” he says.

“There are also façade and cladding costs, which rises significantly from £500-£600 per sq m, to £900-£1,000 per sq m, depending how you do it.”

“But the real problem is getting hold of the right contractors and subcontractors, because funders want to see contractors with experience if you are talking taller buildings.”

The China connection

“Standing room only,” says Hamish Pound, reflecting on his most recent presentation to Chinese investors interested in Manchester apartment schemes.

“Chinese buyers know the city because of the football, the music, the university – they know it better than other UK cities – but what they don’t know, and want to hear about, is the investment case,” says Pound, senior investment manager at IP Global.

And the Chinese influence is already being felt. Last month, a joint venture between the Hauling Group of the People’s Republic of China, Singapore’s Metro Holdings and the Scarborough Group, completed sales at their £30m Hat Box residential development in New Islington. All 405 apartments are now sold at the Milliners Wharf site.

Shanghai-based PGC Capital is also understood to be in talks about a Manchester scheme.

Retail investors are also active, says Andy Phillips, commercial director at Knight Knox, the specialist provider of buy-to-let Manchester developments to the private investor market.

“About half our sales are to overseas investors, mostly the Far and Middle East,“ he says. “They see capital growth of 10% annually, yields of 6%, both better than London, and so we’re seeing an influx.”