Where does the money received from commuted sums actually go? EG launched an investigation into the lost affordable housing cash

What if council leaders around the UK woke up one morning and found they had more than £1bn sat in their coffers to lavish on the affordable housing crisis? Would that be a dream which, while not solving the crunch, would begin to build a better future?

What if council leaders around the UK woke up one morning and found they had more than £1bn sat in their coffers to lavish on the affordable housing crisis? Would that be a dream which, while not solving the crunch, would begin to build a better future?

What if Estates Gazette told you that was the truth?

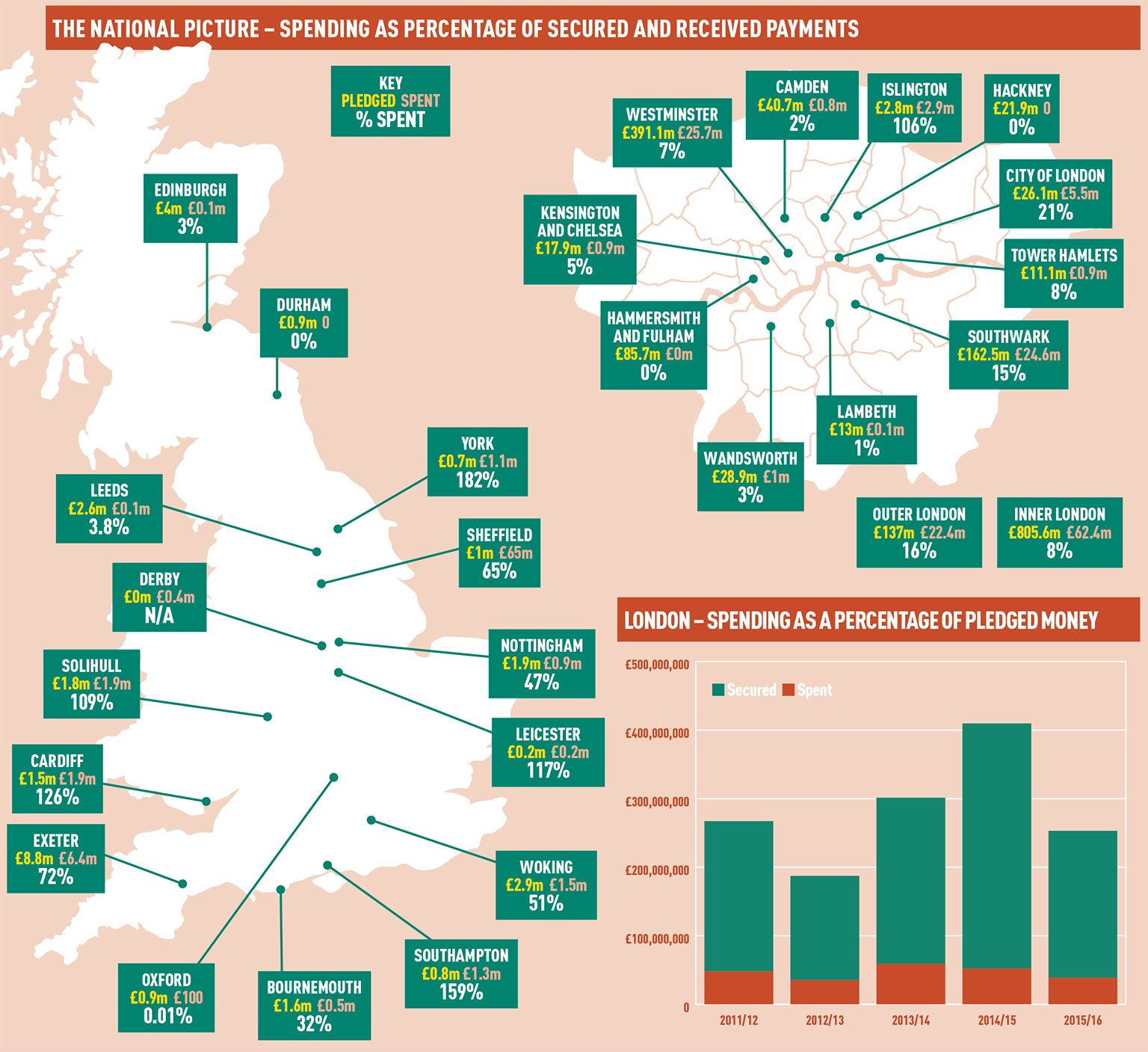

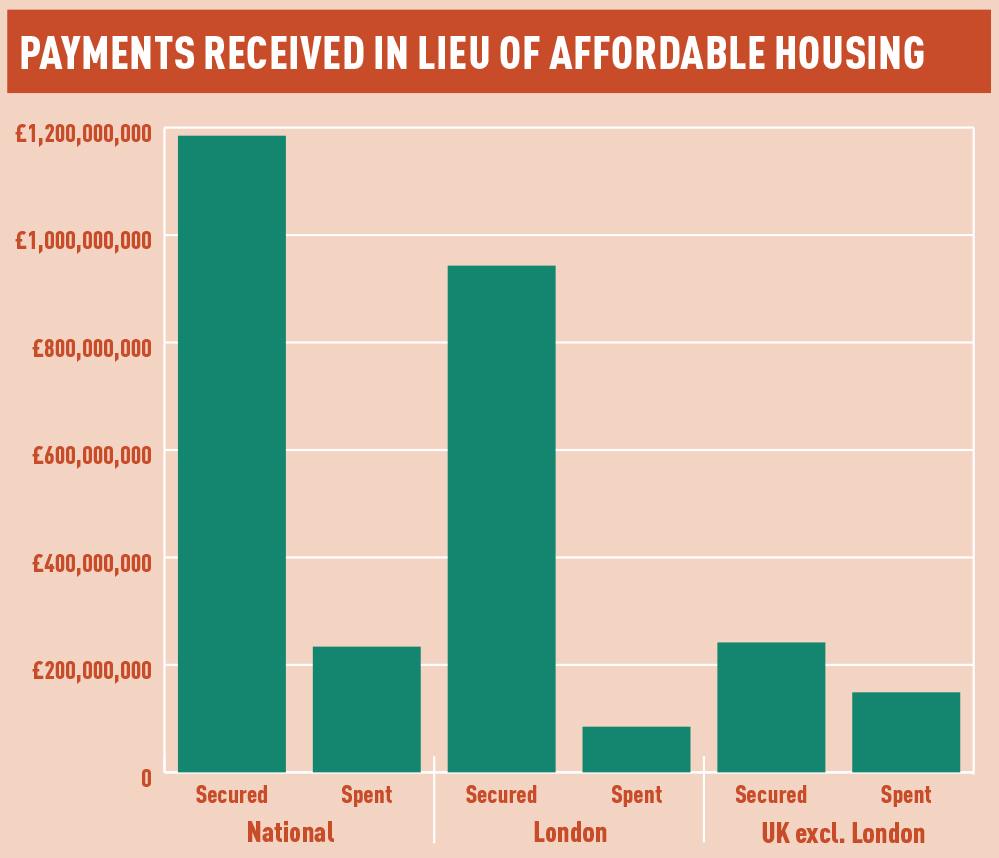

Over the past five years developers have pledged £1.2bn to UK councils through commuted payments for affordable housing. Over the same period, just a fifth of that amount has been spent.

Using requests under the Freedom of Information Act submitted to more than 380 UK councils, and publicly available information, Estates Gazette found that £1.2bn has been allocated to councils since 2010, while just £234m, or 20%, has been spent.

As anger mounts from protest groups about developers’ social responsibility to ease the housing crisis, who is really to blame for the lost £1bn?

This is a London story. It was not intended to be – the provision of affordable housing is a national issue – but over the past five years developers outside the capital have paid only £241m in commuted sums, of which 62% has been spent (see below for a full breakdown of regional figures).

By comparison, London was promised more than three-quarters of the £1.2bn of commuted payments. Incredibly, £805m of that was from the inner London boroughs, meaning 67% of the entire total pledged across the UK in the past five years has been from just 11 local authorities. Spending over the same period amounts to around 8% of that.

You do not have to dig for long to find anger over the councils’ use of money.

“Tightening up the oversight and use of this money would be very welcome,” says Darren Johnson, Green Party London Assembly member. “But it won’t address the fundamental flaws with off-site provision, including the tendency for councils to stick the affordable housing in the cheaper neighbourhoods so we don’t get mixed communities.”

But are the authorities solely to blame?

The blame game

When looking at the bigger picture it is best to start at the top, at the national level.

Generally, commuted sums, under the National Planning Policy Framework, are only allowed after all other avenues of affordable housing provision have been exhausted.

Specifically, when off-site provision or a financial contribution of broadly equivalent value can be robustly justified (for example, to improve or make more effective use of the existing housing stock) and the agreed approach contributes to the objective of creating mixed and balanced communities.

Essentially, for the vast majority of authorities, they are a last resort, and this leads to the immediate problem of councils not having the resources to allocate the cash or spend it effectively.

According to one national developer, who preferred not to be named, councils struggle to spend the money as their capacity has been shredded over the past few years. As a result, it is not easy for them to plan sensibly for the delivery of the infrastructure the monies are intended for.

“Spending the money, this is where the councils struggle,” says Anthony Lee, senior director of development consulting at BNP Paribas Real Estate. “Because many of them are not geared up as developers any more – that skill has largely disappeared.”

There are various ways councils are able to spend commuted payments: through funding housing associations, building their own, or even through refurbishing existing stock.

But this all requires expertise and established mechanisms. In the 25 years since the Town and County Planning Act 1990, and more recent squeezes in authority budgets, many authorities have lost the expertise.

But on-site provision is policy, not law, and over recent years councils have been increasingly comfortable accepting payment in lieu of on-site provision. Estates Gazette’s investigation found a 135% increase in the amount of commuted payments secured between 2012/13 and 2014/15 – 193% in London, and 11% around the rest of the UK.

A large proportion of this will come from the resurgent residential market and rising deal numbers, but anecdotal evidence suggests councils are also increasingly willing to accept the payment.

London

It is no surprise that London receives the lion’s share of the money. With higher land values and greater land constraints, the viability of providing affordable housing on site falls. Even if councils have the experience, and the knowledge, it is not always viable for them to spend.

It is in London where the housing crisis is most acute. The average house price is 12 times the average wage, and the mayoral front-runners have made provision the top priority. The lack of affordable housing provision is in danger of creating a divided city that relegates social tenants to the suburbs.

The considerable cost of providing affordable units on site means more homes could technically be provided elsewhere through commuted payments. This means a hypothetical registered provider could pay as little as £200 per sq ft for units on a scheme valued at £1,400 per sq ft – which means a loss of £1,200 for every sq ft delivered.

In this way, commuted payments make sense for developers and councils. “On some sites the philosophy of mixed communities is very important. On other sites, commuted payments can make sense,” says the developer.

Even within London there are shades of grey. Spending in the capital amounts to about 9% of the money pledged in the past five years. In Westminster, spending is about 6.6% of the money pledged in payments.

Westminster City Council says all the money will be spent, and it does have a number of years yet to use it. When asked about total spending compared to receipts, the council says it has all been allocated.

“The council is currently embarking on its largest regeneration programme, which will deliver up to 1,400 additional homes over the next eight years. This has in part, been made possible by combined existing affordable housing fund contractual commitments and future AHF investments,” a council spokesman says.

Some may think Westminster’s conundrum is largely due to it being a victim of circumstance: it is an expensive borough, with a number of listed buildings and conservation areas.

But it is not alone. Viability constraints are an issue across inner London. On average, spending amounts to about 8% of the current level of cash secured.

Southwark, which has agreements in place for £163m, had similar viability issues towards the northern end of the borough on prime riverside developments, so it used the opportunity to fund more housing elsewhere.

So far, it has spent £25m, or 15%, and this is set to increase. “The preference is for on-site affordable housing” says Mark Williams, cabinet member for regeneration and new homes at Southwark Council. “But in those rare cases where on-site would not be affordable, then we take the commuted sums to build council homes.

“With the few cases on the river we are pragmatic, which leads to many more houses.”

The current council ran a consultation on how best to provide affordable housing when it came to power in 2010. How payments in lieu were to be used was an important part of this.

Contributions will be used to build new council homes across the borough, as part of the council’s commitment to delivering 11,000 new council homes.

Crucially, the borough is still the third-largest council homeowner in the country, with 36,000 units under management, and thus has the processes in place to spend the money.

But this still takes time. “All the money we raise though commuted sums is being and will be spent on new council homes, which will be council tenancies on council rents,” says Williams.

Uppermost in the minds of the councils is the need to increase their efficiency to ensure they are getting the most from their money.

How to spend it

It is clear that councils have just as much trouble providing affordable housing as developers do. Some have questioned whether they should take affordable housing payments at all.

“Commuted payments will become more important under new regulations, so we need to find more ways for authorities to spend it,” says Michael Lowndes, executive director at planning consultancy Turley.

A British Property Federation spokesman adds: “Commuted sums are certainly no bad thing, especially when the provision of affordable housing simply would not work on-site, for instance with build-to-rent developments.

“However, there are clearly challenges around ensuring that commuted sums are spent. For those with high land values it is often even more difficult to get to the stage where they have collected enough to deliver.”

Saving up enough to actually develop a scheme is one reason why it takes a long time to spend the money. So too is finding viable sites, where the price of land works.

“It is always the issue with payment in lieu,” says BNP PRE’s Lee. “Land is scarce, and you are competing with other builders.”

Even when separate affordable schemes are available, there is the very legitimate concern of social cleansing – a problem that also rears its ugly head when considering giving the funding to other boroughs through nomination rights.

Martha Grekos, partner and head of London planning at law firm Irwin Mitchell, says: “To take money in then send it somewhere else, locals would be asking why the council is not supporting them, alongside the wider outcry of sending your problem to another borough, creating segregation”

The whole debate needs an injection of new thinking, something that will be increasingly important in the coming years.

How the UK spends commuted payments

Outside London, as would be expected, contributions were considerably lower as land values and the cost of schemes make on-site affordable commitments more viable.

Just £242m has been received in payments in lieu since 2011. Averaged out across all authorities, it amounts to only £159,606 per year – enough to build just three or four houses.

Only eight authorities outside London received more than £5m, and even large regional centres received relatively small amounts (see table below).

While the sums may be smaller, councils have shown considerably more aptitude in spending it, on average using 63% of the funding, though a large part of this is due to the fact it is easier to spend less money, as cheaper land values makes affordable schemes more viable.

Alongside this, says BNP PRE’s Anthony Lee, many schemes are brought forward through rural exception sites – greenfield sites owned by the council that can be developed if they consist entirely of affordable units.

Birmingham received £2.4m in the five years to 2015 and spent £3m. According to a council spokesman, monies received in lieu of affordable housing were ploughed back into the Birmingham Municipal Housing Trust.

“[Outside London] it is much easier to spend the money,” says Charles Mills, partner and head of planning at Daniel Watney. “The council itself has a much less developed estate on which to provide affordable housing and the availability of land is far easier.”

Methodology

Estates Gazette submitted Freedom of Information request to all councils outside London asking how much they had spent in commuted payments against what they had received.

In London, EG used its own research to see how much councils secured, and asked councils how much they had spent. Monies pledged have not necessarily yet been received by councils, but this gives an indication of how spending compares to the amounts they are receiving through commuted payments.

The quality of response to FOI requests also varied, with reporting periods differing sightly between councils. Assumptions have been made, but every endeavour has been made to maintain accuracy.

• To send feedback e-mail alex.peace@estatesgazette.com or tweet @egalexpeace or @estatesgazette