Piers Harrison and Craig Lonie make a case for revaluation of the deferment rate, a vital component of the calculation of any enfranchisement claim

The deferment rate is a key input in every enfranchisement claim, whether it relates to the enfranchisement of a house or block of flats, or the extension of a flat lease.

The current deferment rate was set by the Lands Tribunal in Earl Cadogan and another v Sportelli and another and similar appeals [2007] 1 EGLR 153, and has been universally adopted since. Is it now time to re-set the deferment rate?

What is the deferment date?

The deferment rate was described by the Lands Tribunal in Sportelli as “the annual discount applied, on a compound basis, to an anticipated future receipt (assessed at current prices) to arrive at its market value at an earlier date”. The formula used by the tribunal was: deferment rate (“DR”) = risk-free rate (“RFR”) + risk premium (“RP”) – real growth rate (“RGR”).

The first two parts of the formula, the RFR and the RP, are an estimation of the rate of return that an investor in property of this kind would demand to hold this kind of investment (as opposed to gilts or equities). The RFR represents the return required by investors when there is no risk of financial loss. It was derived from expert evidence as to the average index-linked yields on a five-year rolling basis over the decade prior to the hearing, in 2006.

The tribunal concluded in Sportelli that the components in the formula were to be given the following values: RFR = 2.25%, RP = 4.5% and RGR = 2%, giving a DR of 4.75%. It was held that this rate was appropriate for cases where the property was a house. In a case where the property consisted of a flat or flats, a further 0.25% (to reflect additional management problems) should be added, giving a DR of 5%. The tribunal concluded that these rates should be regarded as generic deferment rates which could be adopted for leases with unexpired terms of 20 years or more.

Grounds for a challenge?

In R (on the application of Wellcome Trust Ltd) v Upper Tribunal (Administrative Appeals Chamber) [2013] EWHC 2803 (Admin), the Wellcome Trust sought to adduce evidence to challenge the RP and RGR set in Sportelli. Ouseley J held that where a party seeks to call evidence to attack the correctness of a guideline case such as Sportelli, such evidence should only be admitted in exceptional circumstances, but that the threshold might not be so high where there has been a change of circumstances.

So is it now time to look again at the RFR? The tribunal in Sportelli derived the RFR from index-linked government bonds. The principal value of these bonds is linked to inflation and therefore does not change in real terms. Yields on these bonds indicate the return over and above inflation expected by investors on safe assets. The tribunal looked at average index-linked yields on a five-year rolling basis over the decade prior to the hearing. So what has happened to index-linked gilts since 2006?

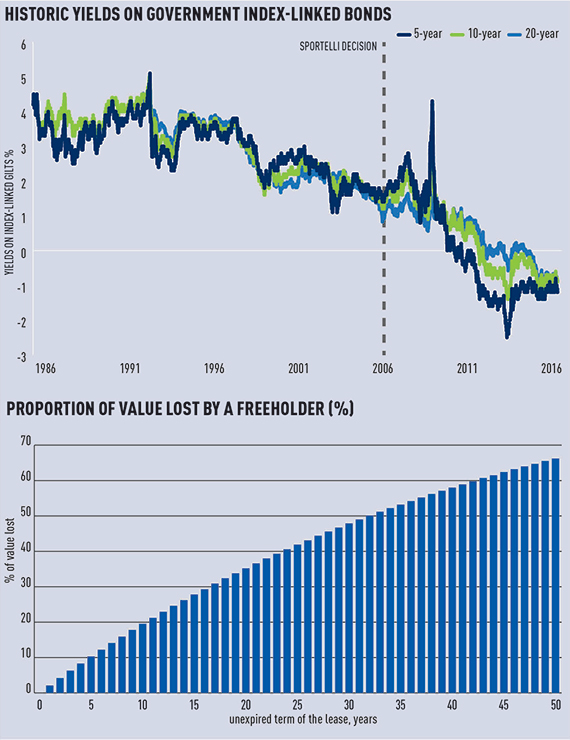

Five-year index-linked government bond yields increased to a peak of 4.3% in November 2008, during the financial crisis that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. Yields then decreased steadily until the start of 2012, with large-scale, internationally coordinated monetary policy intervention likely to have been a major contributory factor. Since the start of 2012, real yields have remained near zero or negative at all maturities up to 20 years. The graph (below) shows the course of real yields since 1986.

As is evident, there has been a marked downward trend in real gilt yields since the Sportelli decision. Were one to recalculate the RFR in February 2016 on the same basis as was adopted in Sportelli, one would arrive at an RFR below zero, potentially as low as –1%.

Obviously the longer the RFR stays lower, the more pronounced becomes the divergence from the 2.25% set in Sportelli. This suggests it may be time for the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) (“the UT”) to review the matter.

One can understand the tribunal being reluctant to allow challenges to the DR too frequently, but it is a decade since the decision in Sportelli and seeking a review on the basis of changes in gilt yields would not be a direct challenge to the decision. It would rather be a matter of updating the decision due to a change in circumstances. Those against reviewing the RFR would say that the present market is distorted by quantitative easing. But there are respectable arguments that this is not a short-term distortion and the world has entered into a secular period of low risk-free returns. Gertjan Vlieghe of the Bank of England monetary policy committee recently warned that the market should “be prepared for the possibility that real interest rates will remain well below their historical average for a very long time”.

Moreover, forward rates (ie rates at which market participants are willing to transact in the future, as implied by current yields) suggest that the RFR is likely to remain close to zero for the next decade at least.

Deferment rate for leases with 10-20 years unexpired

In Earl Cadogan and another v Cadogan Square Ltd; Cadogan Square Ltd v Earl Cadogan [2011] UKUT 154 (LC); [2011] 3 EGLR 127, the UT adopted the formula of DR = RFR + RP – RGR, but adjusted RGR to take account of expert evidence that, as at the valuation date, there had been an extended period of above-average growth and a period of sub-trend growth could be expected to follow.

There are some criticisms of that approach. No expert can predict the property cycle. In the very long term there is always reversion to mean, but during a period of 10-20 years it is possible for an overvalued market to get more overvalued and for a falling market to fall further. As John Maynard Keynes said, “Markets can remain irrational a lot longer than you and I can stay solvent.”

The second criticism is the use of the same long-run RFR as is used for unexpired terms of more than 20 years. It is possible to match the spot rate yield at the valuation date for a term commensurate with the term of the unexpired term of the lease. Since the spot rate captures market consensus as to the direction of the change in yields, this is a preferred approach by financial practitioners.

To illustrate, current evidence from index-linked gilts of various maturities suggests that, for a lease with 20 years outstanding, the appropriate RFR is –0.9%. In contrast, if the lease has only five years outstanding, the appropriate RFR dictated by the market is –1.21%.

Implications for valuation

The difference between the numbers in the Sportelli decision and current market evidence may seem small, but, when compounded over years, it has a profound impact on value. The bar chart (above) provides an approximate illustration of the proportion of value which a freeholder would lose today, due to an outdated assumption on the RFR being used.

It assumes a rate of zero for all leases. Due to current market evidence pointing to a lower value of the RFR, this represents a conservative assumption.

Thus, especially now, when gilt yields are depressed and expected to remain so for some time, it seems appropriate for shorter leases to consider contemporaneous market evidence. Failure to do so runs the risk of significantly underestimating the value of enfranchisement claims and therefore materially distorting the UK property market.

Piers Harrison is a barrister at Tanfield Chambers and Craig Lonie is an economist and partner at Oxera