The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards may be mainly a landlord problem, but Ed Glass and Nick Hogg explain why tenants should also take note

Fundamentally, the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (“MEES”) are a landlord problem – the statutory obligation to comply and risk of financial penalty falls on them, not the tenant. However, MEES can have an impact on tenants, both on the grant of a new lease and under an existing lease.

A tenant may have a right and need to underlet, where it itself will be subject to MEES. Moreover, the terms of an existing lease, or (perhaps more likely) the terms sought by a landlord in a new lease might attempt to shift the practical and financial burden of compliance to the tenant. With deadlines approaching, it is not only landlords that are well advised to take note and be proactive.

The MEES opportunity

In negotiation on new leases, MEES has the potential for contention as landlords may look to enhance landlord rights, increase tenant restrictions and otherwise shift the burden of MEES compliance to the tenant. There is also scope for contention in existing relationships, as landlords look to address MEES risk under the terms of existing leases (for example, requiring access to carry out work).

However, MEES need not necessarily be a source of confrontation. Instead, MEES may present an opportunity for collaboration between landlords and tenants from which both can benefit. On one level, a landlord may need to carry out work in advance of the deadlines, perhaps looking to “future-proof” its asset against rising thresholds and the risk that MEES may have a detrimental effect on value. On another level, the tenant may benefit from reduced outgoings in a more energy efficient building, and may have concerns in the context of underletting. Yet as fundamentally a “landlord problem”, it is inevitable that the balance of opportunity here rests with the tenant. How can a tenant harness the position on MEES in its existing or potential relationship with the landlord?

Engaging with a landlord during the term

For a tenant under an existing lease that spans the 2023 deadline, and in a building with “MEES risk”, a landlord will inevitably engage with the tenant in advance. In addition, a landlord of an existing lease, expiring before 2023, may well look to address the MEES risk now and avoid future voids while work is carried out. The landlord’s rights will depend on the lease terms and, until recently, it is unlikely that a lease will have been drafted with MEES in mind. A tenant in such a position might ask:

- What are the landlord’s rights to access and carry out improvement work, and at whose cost?

- Is the repairing or statutory compliance covenant drafted to shift the burden of compliance?

- Is this an opportunity? Can the tenant leverage its position to negotiate improvement work and benefit from enhanced building performance?

The landlord-tenant relationship under an existing lease may well present further opportunities. There may be scope to negotiate a preferential lease regearing while addressing energy efficiency improvements and their cost in negotiation. In addition, the tenant’s ability to force the landlord to carry out upgrades may be a factor in deciding whether to exercise a break right. In a similar manner, for a tenant of a lease nearing expiry and debating whether to renew or move elsewhere, it may leverage the landlord’s MEES position in negotiation.

The terms of any existing lease may also impact on the tenant’s right to underlet, where it will need to obtain an energy performance certificate (“EPC”) or rely on the landlord’s existing EPC. For a tenant occupying under an existing lease that spans the 2018 deadline, but wishing to underlet after that date, the MEES restriction will impact the tenant first, not its landlord. From April 2018, a tenant must comply with MEES to underlet. Can the tenant freely obtain its own EPC (especially if it is not in a position to rely on the landlord’s, or the landlord’s EPC records an F or G rating)?

If the tenant’s lease is such that it cannot obtain its own EPC and/or carry out necessary improvement work, how does the tenant lawfully sublet after April 2018? A tenant may look to engage with its landlord, who will no doubt have MEES in mind, and look to collaborate on improvement work that will ultimately benefit both. If the tenant cannot carry out MEES improvement work because, for example, the landlord does not consent to it, the tenant will have to rely on a MEES exemption and assume the administrative burden of registration before it can underlet.

Engaging with a landlord at the expiry of the term

A tenant vacating at the end of the term is likely to have dilapidations and reinstatement liabilities under the repairing and yield-up covenants. For a tenant exiting a poorly rated building, and with the statutory restrictions set to bite, MEES has the potential to force the landlord into redevelopment or refurbishment work, potentially enhancing the prospect of supersession arguments. Where a tenant has made alterations which improve energy efficiency during the term, MEES may prompt a landlord to retain any such work, which it might otherwise be in a position to require the tenant to reinstate. As such, for a tenant, MEES has the potential to limit or remove liability and should not be overlooked at expiry.

Engaging with a landlord in a new letting

MEES may present buyers of poorly rated stock with the opportunity to enhance value and tenants might benefit from similar opportunities. Rather than immediately discounting F- or G-rated stock in a market where poorly rated stock will become more and more difficult to let, tenants may be in a position to extract concessions from landlords (perhaps in exchange for carrying out works). In considering a property that it might have otherwise discounted, this may enable a tenant to achieve a property better suited and equipped to its needs at neutral cost.

For the future, landlords may look to “MEES-proof” new leases to the extent existing drafting is not sufficient. For example, with the enhanced importance of EPCs, a landlord will want (arguably justifiably) to protect its EPC position by increased restrictions on tenants obtaining EPCs and conducting alterations. Landlords may well go further, for example, specifically attempting to pass on the costs of MEES compliance to the tenant and buttressing rent review provisions in its favour. Tenants should anticipate this and, with the respective position of landlord and tenant under MEES in mind, assess what it considers is a satisfactory position. For example, if a landlord insists that the tenant conducts improvement work, perhaps as part of an agreement for lease, a tenant might be well placed to argue for a capital contribution and justify a limitation on its reinstatement obligations at the end of the term. Furthermore, tenants should ensure that the terms of any new lease do not prejudice their right to underlet.

Knowledge is power

The MEES legislation is clearly aimed at landlords but it is also important that tenants are aware of the approaching restrictions. Tenants will then be in a position to anticipate and understand how changes will affect them, including the implications of an F or G rating on the tenant’s occupational interest, the interpretation of lease terms and the alienation rights it believes it has negotiated/are under negotiation. A tenant may well even benefit from such an awareness in commercial negotiations as it considers taking, continuing with or renewing a lease. Certainly from both parties’ perspective, the implications of MEES are best addressed in heads of terms, therefore minimising the chance of stalling in lease negotiation.

A reminder for landlords on MEES and EPCs

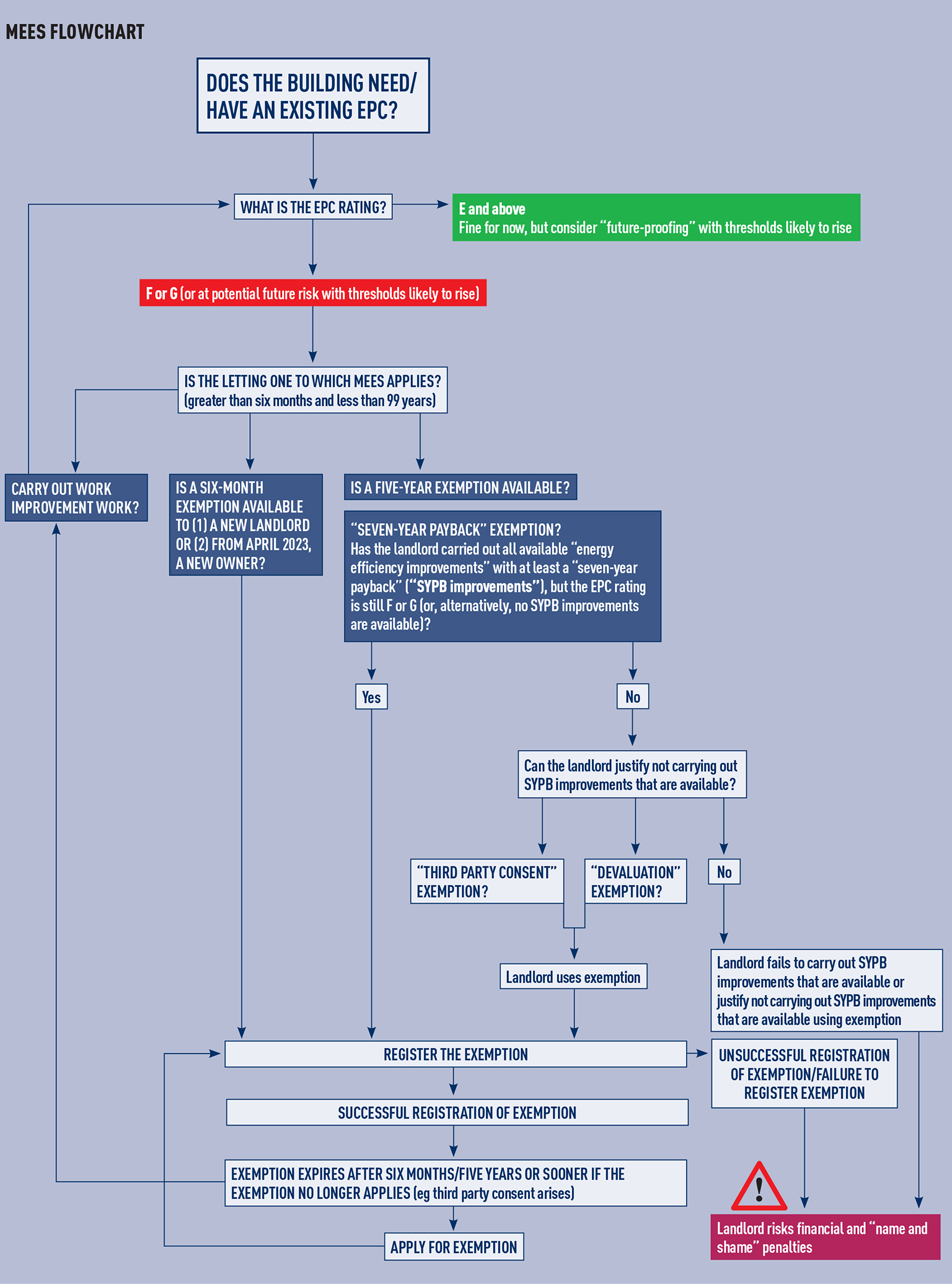

In 2015, the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (“MEES”) came into law. Therefore, from 1 April 2018 it will be illegal for a landlord to grant a new letting of a commercial property that has an energy performance certificate (“EPC”) with an F or G rating. From 1 April 2023, this restriction will apply to all lettings. As explored in “A guide through the MEES minefield” (EG, 25 April 2015, p76), exemptions may be available to a landlord (also see the MEES flowchart, below).

While there is still time before the restrictions bite, many landlords are quite sensibly assessing the need for a proactive approach to evaluating and, if necessary, confronting MEES risk. Possible steps include:

- improving the energy performance of a building now, establishing an EPC rating that is well beyond the MEES minimum threshold (which is anticipated to increase with time), and therefore avoiding the potential future need to rely on an exemption; and

- drafting new leases to manage MEES risk.

A previous article by the authors considered this need for landlords and potential landlords to think ahead (“Putting MEES first”, EG, 8 August 2015, p48), particularly to the extent that MEES may impact on investment value. There is no doubt that MEES will impact more and more on landlord thinking, and, as the restrictions loom closer, will become an increasingly important consideration not just on sale/purchase, but also in landlord leasing strategies leading up to the relevant dates.

What is the EPC status of the building?

In considering MEES obligations, the first question is whether an EPC is needed and/or whether an existing EPC is in place (ie one has been formally lodged on the public register). Certain buildings do not require EPCs, and, importantly, MEES only bites to the extent an EPC is in place, whether it is required or not. In addition, for an incoming purchaser of property subject to leases, it will be concerned to see if any tenant has an EPC in place that may otherwise trump that of the landlord. A related consideration is whether and the extent to which a tenant may obtain its own EPC and potentially prejudice that of the landlord.

How accurate is the EPC?

The accuracy of ratings will command scrutiny as more reliance is placed on EPCs during transactions, especially if those ratings identify MEES risk. Concerns have been raised generally about the questionable accuracy of EPCs, particularly some of those lodged in the immediate years following the introduction of the EPC regulations in 2008. Furthermore, the calculation methodology, which underpins the data assumptions on which ratings are based, has changed over time as updates to building regulations have been made. This will continue, at a pace ahead of the 10-year lifespan of an EPC.

The principal consideration here then is due diligence on the accuracy of the EPC itself, and whether it a true reflection of the current state of the space being assessed. The input data used to prepare the EPC is key – the more assumptions are made, the less representative the EPC could be. If there are concerns about the accuracy of existing EPCs, a landlord or incoming purchaser may choose to commission or require fresh EPCs, using trusted outfits and ensuring any assessor has access to the information it requires. A further option is to undertake an exploratory first step by commissioning a draft EPC to assess risk, which does not need to be formally lodged on the register.

Ed Glass is an associate at Bristows LLP and Nick Hogg is an associate director at Sustainable Commercial Solutions