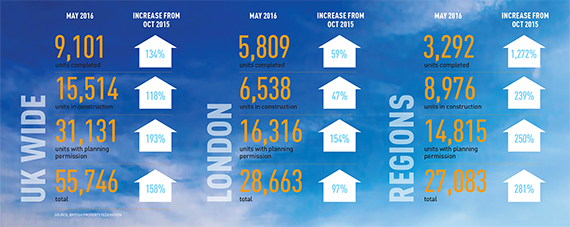

What a difference a year makes – no, make that just six months. During the winter, build to rent (BTR) still seemed in its infancy, but since then the number of units with consent, under construction or completed has soared from 22,000 to 55,000; a trade body, the UK Apartment Association, has been formed; and the Association of Residential Letting Agents – a group heavily involved in traditional buy to let – now has its first BTR institutional member.

What a difference a year makes – no, make that just six months. During the winter, build to rent (BTR) still seemed in its infancy, but since then the number of units with consent, under construction or completed has soared from 22,000 to 55,000; a trade body, the UK Apartment Association, has been formed; and the Association of Residential Letting Agents – a group heavily involved in traditional buy to let – now has its first BTR institutional member.

Combine all that with the British Property Federation’s success in persuading industry and policy-makers alike to champion time-restricted covenants for build to rent units – instead of a separate planning use class, which was unpopular with some investors – and the sector looks increasingly mature. In other words, it’s here to stay.

So what happens now, as build to rent moves into its next phase of acceptance?

Firstly, a more established investment model is slowly evolving which is likely to be a major theme of the sector in the next three years, say many players.

Richard Green of Venn Partners, appointed by the government as delivery partner for its £3.5bn BTR guarantee scheme, says that for the moment, the market is characterised by a plethora of business models from players dipping their toes in the water.

“The market is much more mature in the US, where borrowers have a wider choice of investors and lenders, including insurers, pension funds, asset managers and capital markets. The UK will move towards that, but it will take time,” says Green, whose firm is set to issue its first build to rent bond later this year.

The extension of the 3% SDLT surcharge on additional homes to bulk-buying institutional purchasers – a late change announced by the chancellor in his spring budget – has upset some in the short term, but has indirectly helped a growing number of investors to espouse a forward funding model.

“This [surcharge] has made turnkey structures even less competitive in comparison to many forward-funding structures [which avoid it]” says Toby Nicholson, director of national capital markets for build to rent at Colliers International.

A second trend as BTR matures will be greater understanding shown by both central and local government. The most obvious area for this is a more flexible approach to planning.

“Local authorities should not be compelled to apply national residential space standards to all developments,” says Andrew Bickerdike of planning consultancy Turley.

Meanwhile, James Cook, planning director at GL Hearn, says local councils are still struggling to understand build to rent’s needs. He has a shopping list of planning improvements, including “more clarity around the Community Infrastructure Levy, affordable housing provision and Section 106 agreements”, as well as more consistency in decision-making.

The integrity of a BTR scheme and the need for investors to build a brand to encourage long-term tenant loyalty is new territory for most planning authorities.

“Starter homes within a development won’t work and on-site traditional affordable housing isn’t ideal,” says Paul Winstanley, a partner at Allsop & Co. “The best compromise is discounted market rent, where providing affordable housing is viable, controlled and managed by the investor rather than a third-party registered provider.”

A third theme as build to rent matures further will be the emergence of suppliers and ‘re-shaping’ of traditional players, such as letting agencies.

“We are seeing an influx of suppliers from the US to meet the needs of BTR operators and the UK market will have to step up to this over time,” says Roger Southam, founder of the UK Apartment Association. The newly formed trade body is establishing training and customer service standards based on the experience of the vast US multi-family sector.

Southam says some existing firms in the old-school buy to let arena are rebadging themselves for build to rent “regardless of skillsets, understanding and delivery”. He feels a major task for the next five years will be to improve service standards beyond those offered by amateur landlords who are far less customer-focused than institutional investors.

So far, so exciting as build to rent continues to grow rapidly.

But one theme unlikely to materialise in the near future is the entry of volume housebuilders into the sector – at least not while profits are to be found more readily by selling to owner-occupiers and traditional buy to let landlords.

“We are developing our homes ourselves as very few existing developers recognise the differences in design required for build to rent,” says Dan Batterton, fund manager for Legal & General Property, one of the sector’s biggest investors, having announced this spring that it would spend £600m alongside Dutch pension fund manager PGGM.

Batterton and other players think the publicly quoted builders may show an interest eventually, although that could depend on a tipping point being reached when build to rent seriously rivals buy to let in the private rental landscape.

With Knight Frank forecasting that institutional investment will provide no more than 5% of private rental stock by 2020, that tipping point is some way off. But if the past six months are any indication, that day may come sooner than many think.

The PRS revolution accelerates

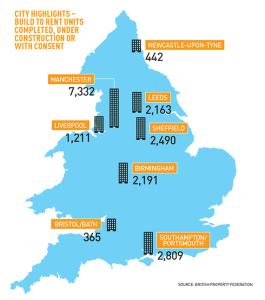

There are at present 55,746 build to rent units completed, under construction or with planning permission in the UK. The split between London and the regions is almost even, with 28,663 in London and 27,083 elsewhere. The increase in these figures in just six months has been startling.