Where now for farming and the rural economy as Brexit draws nearer? An immediate worry for farmers has been the future of direct support payments. The Treasury’s announcement on 13 August makes it clear that the main plank of this support, the Basic Farm Payment, is now guaranteed until 2020. Agri-environment schemes agreed before this year’s Autumn Statement will also be fully funded, even beyond the date of Brexit itself. With a September deadline approaching for the latest applications, the Country Land and Business Association (CLA) has been encouraging members to crack on with applications.

Where now for farming and the rural economy as Brexit draws nearer? An immediate worry for farmers has been the future of direct support payments. The Treasury’s announcement on 13 August makes it clear that the main plank of this support, the Basic Farm Payment, is now guaranteed until 2020. Agri-environment schemes agreed before this year’s Autumn Statement will also be fully funded, even beyond the date of Brexit itself. With a September deadline approaching for the latest applications, the Country Land and Business Association (CLA) has been encouraging members to crack on with applications.

Doubts remain over schemes which might still be under negotiation beyond the Autumn Statement. Despite this, new environment secretary Andrea Leadsom said this guarantee of funding is “excellent news for our farmers and our environment”.

Work is to begin on a new domestic agricultural policy and the major organisations with an interest in farming and the countryside have begun to set out their ideas. But first, just how important are the Basic Farm Payments to UK farmers?

Importance of subsidy payments

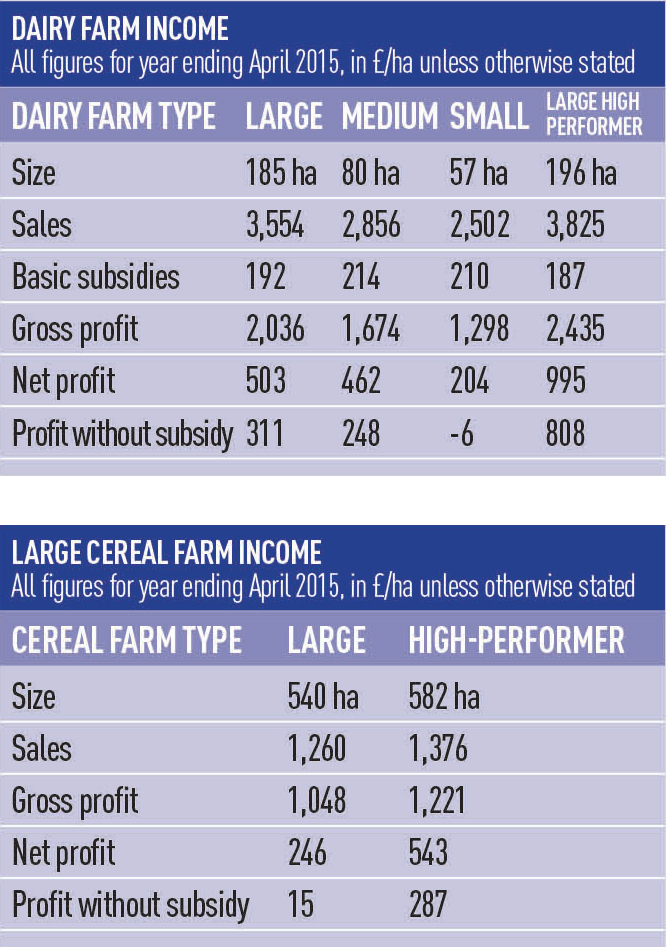

An annual government Farm Business Survey records details of income and expenditure for all the main farm types. The figures for dairy farming for the year up to April 2015 are shown in the first table.

The plight of the smallest dairy farmers can be seen clearly, a net profit of £204/ha with subsidy and a loss of £6/ha without it. These data show the gap between the best and the rest in economic performance. The high-performing large dairy farm is almost £500 per hectare ahead of its average counterpart in net profit. Even with the loss of subsidy it will still be making more profit than its average counterpart is doing with subsidy. Cereal farms are little different as shown by the data in the second table for large cereal farms.

Once again the high-performing large cereal farm makes more profit without subsidy than its average performing counterpart with subsidy. The message for farmers who want to survive and prosper in the new farming economy is clear: you must excel. The guarantee of direct subsidy payments at present levels until at least 2020 is a welcome reassurance to ensure that current funding levels of £3.1bn a year will be maintained, but may also herald the danger of complacency about current performance. What might the new policy environment look like after 2020?

New policy environment

The CLA was the first into the fray with six demands to support the farming industry in the transition to Brexit. First, no tariffs to be imposed on trade with the EU. All existing international trade agreements that rely on our EU membership must be replaced on at least equal terms. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) should stay in place until 2020 – a reassurance now given by the Treasury – while a UK Agricultural Policy must be developed. Regulation and labour featured in the remaining two demands: a call for a framework to ensure that all EU rules and regulations are reviewed, and continuing access to EU labour for farm work.

The National Farmers Union (NFU) has launched its biggest member consultation in a generation, with a deadline of 14 September for feedback. Like the CLA, it demands access to the £8.9bn EU market for agricultural and food produce. We must replace more than 50 trade agreements which give us access to other world markets. Imports should be curbed where production complies with lower standards than home-grown produce. Farmers must have access to labour from anywhere in the world, controlled by a suitable visa scheme. Domestic agricultural policy should maintain support on at least a par with EU support. Environment schemes must be improved and regulations must be proportional and based on sound science.

The National Trust has taken a different tack. In a speech at the Countryfile Live event in Oxfordshire on 4 August, director general Dame Helen Ghosh put forward six principles. Public money should only be paid for public goods. It should be unacceptable to harm nature by inappropriate farming methods, but easy to help it. The new policy should result in an abundance of nature everywhere. It should drive better outcomes for nature, both long-term and on a large scale. Farmers who deliver more public benefits should be paid more. We should invest in science, new technology and new markets that can help nature (perhaps aimed at carbon storage, flood prevention and the promotion of bio-diversity). Ghosh argues that it is for food manufacturers and retailers to pay the proper price for produce, and for utility companies and tourism to pay for water and leisure benefits.

The debate has hardly begun to consider the wider elements which might make up an agricultural policy: the new entrant problem, science investment, how new knowledge gets into practice, the role of taxation and how to foster a truly competitive and sustainable farming industry. For many the answer needs to start at home: how efficient are your farmers and how will this be reflected in rents and agricultural investment yields over the next 10 years?

Charles Cowap is a rural practice chartered surveyor