Expectations for the world’s emerging economies – Brazil, Russia, India and China, and Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey – have been slashed by falling oil prices, instability and other factors. Janie Manzoori-Stamford delves deeper

Expectations for the world’s emerging economies – Brazil, Russia, India and China, and Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey – have been slashed by falling oil prices, instability and other factors. Janie Manzoori-Stamford delves deeper

In 2001, Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill coined the term BRIC. The now-familiar acronym grouping together Brazil, Russia, India and China was meant to be the ultimate guide for international investors; these were the countries expected to see huge growth rates.

In short, they were the countries everyone should have firmly on their radar. Then, last year the bank quietly closed its dedicated BRIC fund – which had lost 88% of its asset value since 2010 – and folded the investments into its larger emerging markets funds.

Hardly a ringing endorsement. But it is not difficult to see why. Now, 15 years on, the BRIC countries are all facing very different, but significant problems.

And it is a similar story for Mexico. Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey – the MINT countries that became the second grouping, announced by Fidelity Investments in 2011, and popularised by O’Neill three years later.

So what went wrong? How, out of a group of eight expertly selected economies to watch, could so many have ended up in such dire straits? Is it simply down to the passage of time, changing market conditions and unforeseeable external events? Or is there more at play?

The eight countries might all be hugely disparate, both culturally and geographically. But they share many traits. And, arguably, shared even more back in the early 2000s: large populations and strong growth rates; rapidly emerging middles classes and entrepreneurial cultures; and governments that appeared willing to embrace global markets alongside some elements of globalisation.

The BRIC and MINT concepts neatly illustrated the way in which the economic balance of power has shifted from the developed to the developing world over the past 20 years. And according to Harry Tan, TH Real Estate’s head of research, Asia-Pacific, it made a lot of sense to highlight them together. “These were big emerging countries that people projected would be both consuming and producing a lot more, that would drive economic growth,” he says. “It was helpful to group them together for some time. But not anymore.”

Fast forward to 2016 and the economic outlooks of these countries look drastically different.

Brazil and Russia are in the grips of recession, the economic reform needed in India for it to fully realise its potential has yet to materialise and China saw its growth decelerate to 6.9% in 2015, its slowest rate in a quarter of a century. The IMF says it expects growth to slow further, to 6.3% by the end of this year, and 6% in 2017.

Using GDP growth to measure a country’s success might not be the way to go anymore (see box) but the MINT countries have their own share of issues, including political instability and slowing economic growth.

Nigeria’s export earnings are inextricably linked to oil prices, a problem for both Mexico and Indonesia too – while Turkey is dealing with a spate of terror attacks and the fallout of July’s failed military coup.

But because of their complex and non-traditional legal frameworks, these markets were not necessarily that easy to exploit even when the good times were rolling.

“That’s probably the story for nearly all BRIC and MINT countries. Some of them are very difficult to get exposure to,” says Yolande Barnes, head of research at Savills.

“You don’t have to go far [beyond the world’s most invested real estate markets] to find much less transparency and different legal systems. And in emerging markets, that’s even more the case.

“There’s a wealth of potential but actually tapping into it is very, very difficult.”

What unites the BRIC and MINT countries today is no longer the promise of untapped, parallel potential. Instead each is mired in its own specific issues. But when unpicked, after careful analysis, investors may identify a unique set of opportunities behind the headline-grabbing hype.

BRIC COUNTRIES

BRAZIL

When president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva left office in 2011, with an 82% approval rating, Brazil was deemed an exemplar of economic and social progress in Latin America.

When president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva left office in 2011, with an 82% approval rating, Brazil was deemed an exemplar of economic and social progress in Latin America.

Demand for Brazil’s commodities was booming, with China its biggest market, and as oil prices peaked, Brazil enjoyed the discovery of major offshore reserves.

A series of social policies and economic programmes helped accelerate national growth, keep inflation and debt in check, reduce poverty and expand the middle class.

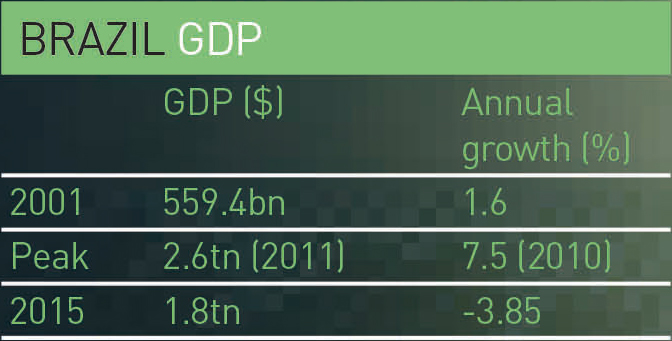

Five years’ later and the country is in the grips of its worst recession in more than 30 years. Its economy shrank by 3.8% last year – the country’s worst annual performance since 1981 – while the end of 2015 saw inflation reached 10.7%, its highest peak in 12 years.

So what went wrong? In short, the economic model implemented by Lula was reliant on the good times continuing to roll. And shortly after his successor, Dilma Rousseff, took office, commodity prices plummeted worldwide. Government revenues fell sharply, but its budgetary obligations remained largely unchanged.

The cost burden of hosting the 2014 World Cup ($15bn) and 2016 Olympics ($4.6bn), as well as ongoing corruption will likely fuel the recession until late 2017.

RUSSIA

Russia’s economy is dependent on oil revenues, so when oil prices saw a spike of around 500% between 2000 and 2008, it was set to prosper.

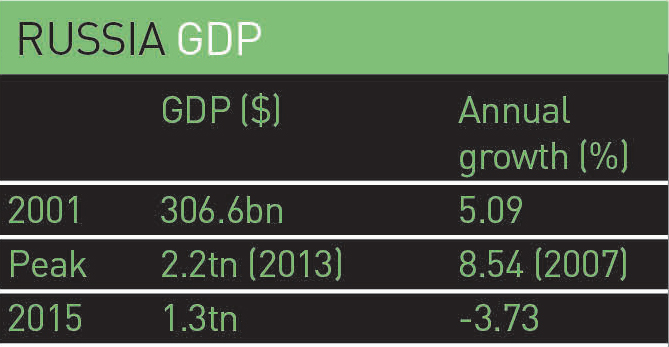

Russia’s economy is dependent on oil revenues, so when oil prices saw a spike of around 500% between 2000 and 2008, it was set to prosper.

The price per barrel went from below $25 at the turn of the century to almost $150 in 2008, driven by surging demand from emerging economies such as China and India.

But Russia’s failure to diversify during the good times has had major consequences.

The global financial crisis put the kibosh on demand for energy and by the end of 2008, oil and gas prices were in freefall. Russia’s export earnings fell and, as a result, so did imports and investments, severely limiting fiscal policy.

International trade was further disrupted by Russia’s annexation of Crimea in the spring of 2014, which led to the imposition of western sanctions. By the end of the year, the rouble had lost 40% of its value, prices had risen and incomes were squeezed.

In December 2015, president Vladimir Putin insisted that the economy had hit bottom and was ripe for a rebound, but one month later the International Monetary Fund further slashed its economic forecasts and warned that Russia will likely stay in recession until 2017.

INDIA

The seeds of India’s 21st century fortunes were sown in 1991. That is when the liberalisation of the economy was initiated with the aim of making it more market-oriented and investor-friendly.

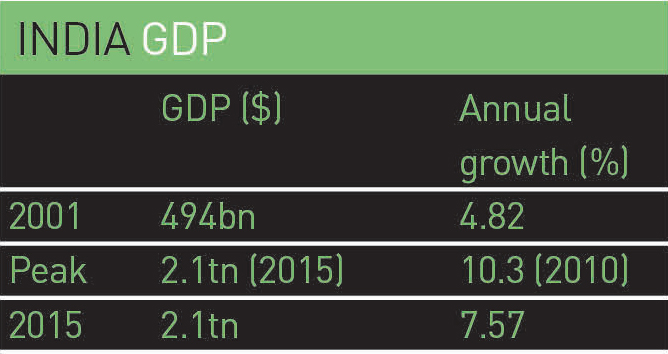

The seeds of India’s 21st century fortunes were sown in 1991. That is when the liberalisation of the economy was initiated with the aim of making it more market-oriented and investor-friendly.

Changes included a reduction in import tariffs and taxes, deregulation of markets and greater DFI. GDP growth, which had remained relatively flat since India’s independence in 1947, began to climb sharply, peaking at a 9% average between 2003 and 2007. As a result, Goldman Sachs predicted in 2003 that India’s GDP would overtake Japan’s by 2035. This would make it the third-largest economy in the world behind the US and China.

But in 2012, growth decelerated to 5.6%. The rupee went into freefall, industrial growth slowed and the US Federal Reserve’s decision to taper quantitative easing led to foreign investors hastily pulling capital out of India.

Recovery began in 2014-15 when the growth rate rose to 7.2% and accelerated further to 7.6% in 2015-16, thanks to a start-up boom and spike in manufacturing. For the first time since 1990, India’s growth rate was faster than China’s (2015: 6.9%), with further acceleration anticipated.

A major economic overhaul, announced in August as the most significant reform since 1991, aims to end the labyrinth of federal and state levies that have stifled economic growth.

CHINA

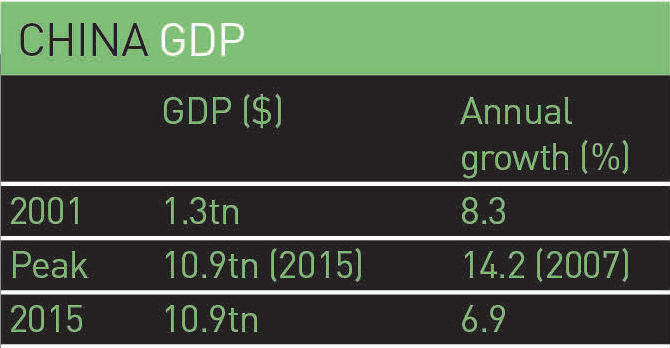

China is arguably the biggest success story of the BRICs, though it is well documented that its rapid, largely unregulated growth trajectory could ultimately prove unsustainable, with major global implications. The country now boasts a GDP 715% bigger

China is arguably the biggest success story of the BRICs, though it is well documented that its rapid, largely unregulated growth trajectory could ultimately prove unsustainable, with major global implications. The country now boasts a GDP 715% bigger

than when it joined the BRIC club in 2001.

And though the rate of growth has cooled, the amount by which the economy expands year-on-year is still on a sharp upward trajectory because of the ever-increasing base.

The impact of the global financial crisis – or the north Atlantic debt crisis, as it is known in much of Asia – was perhaps not immediately apparent. GDP growth fell from a high of 14.2% in 2007 to 9.23% in 2009, before rising again to 10.6% the next year.

The 2008 global downturn hit the country’s key export cities such as Guangzhou and Shenzhen because an absence of export credit had effectively brought the market to a standstill. So the government tried to slow the rate of deceleration gently rather than allow a crash landing.

In response, China’s central government introduced a $586bn (£440bn) stimulus programme, which boosted not just the country’s economic growth but also demand in countries exporting to China.

MINT COUNTRIES

MEXICO

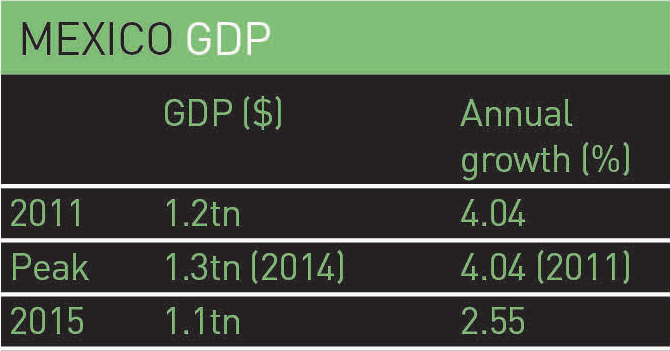

Mexico has long been considered a rising star among Latin America’s emerging economies. It has a substantial manufacturing sector that makes sophisticated products and is becoming integrated into US supply chains. Yet the economy grew at just 1.3% in 2013, its slowest rate since the 2009 recession, and a far cry from the 4% achieved in 2012, the year president Enrique Peña Nieto took office.

Mexico has long been considered a rising star among Latin America’s emerging economies. It has a substantial manufacturing sector that makes sophisticated products and is becoming integrated into US supply chains. Yet the economy grew at just 1.3% in 2013, its slowest rate since the 2009 recession, and a far cry from the 4% achieved in 2012, the year president Enrique Peña Nieto took office.

Much of the 2013 stagnation is the result of a slowdown in manufacturing in the US, which buys around 80% of exports. A lack of haste by the incoming government in implementing its investment programmes was not helpful, while changes in housing policy threatened to close down credit to housebuilders for the first half of the year.

A challenging global economic environment and falling oil prices – 32% of government revenue stems from oil exports – continued to put a damper on Mexico’s economic prospects. GDP growth rates climbed in both 2014 (2.25%) and 2015 (2.55%), but fell short of expectations; Mexico’s ministry of finance estimated that the economy would grow by between 3.2% to 4.2% last year.

But there is strength in Mexico’s political and economic outlook. The PRI party in government is working well with the PAN party to push through reforms that seek to broaden the country’s sources of revenues.

INDONESIA

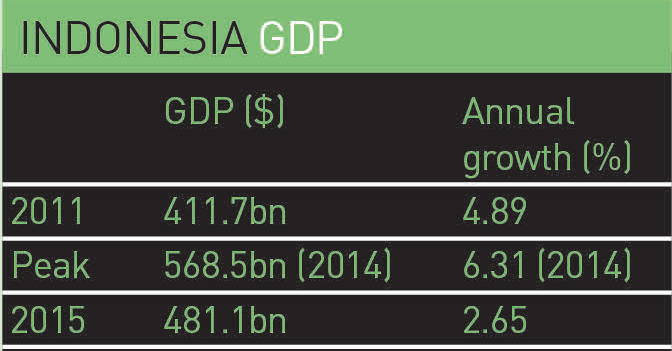

Commodities play a massive part in Indonesia’s economy. It is the world’s leading exporter of palm oil and tin, the second-largest rubber exporter and fourth-biggest coal producer. It is also home to the world’s biggest gold mine and third-largest copper mine.

Commodities play a massive part in Indonesia’s economy. It is the world’s leading exporter of palm oil and tin, the second-largest rubber exporter and fourth-biggest coal producer. It is also home to the world’s biggest gold mine and third-largest copper mine.

When cross-border demand for commodities is high, Indonesia benefits from strong demand from China, its second-biggest export market after Japan. But as China’s appetite for raw materials has weakened, so too has Indonesia’s economic growth.

President Joko Widodo took office in 2014 vowing to make it easier to do business, boost spending on infrastructure, and rebalance Indonesia’s economy.

It is well-placed for such a shift. Indonesia, the world’s fourth-most populous country, has a huge, fast-urbanising domestic market, a rising consumer class and a relatively cheap workforce.

But the country’s GDP growth rate in 2011, when it joined the MINT group, was 6.17% and it has been slowing ever since. Indonesia’s geography – it is sprawled across some 13,000 islands – means that getting goods from one place to another will be complicated and costly, which makes good policy vital.

While Widodo is riding high in opinion polls, thanks to savvy political manoeuvring, the expectation that the country’s first leader not to come from the military or political elite might shake up the establishment is looking less likely to be met, say critics.

The inconsistencies in Widodo’s policies have led analysts to say that after nearly two years in office, it is still not clear if he favours the free market or protectionism.

NIGERIA

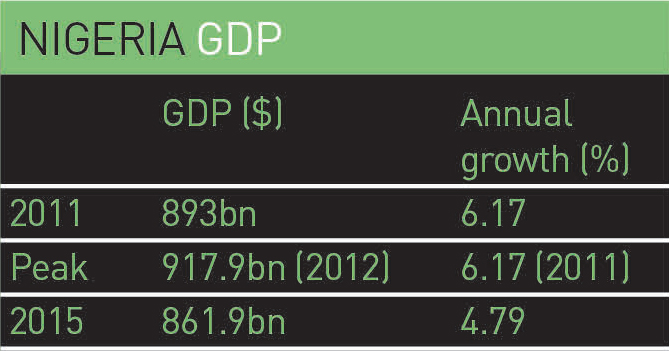

Oil is Nigeria’s main source of foreign exchange earnings and government financing, accounting for 11% of total GDP, 70% of government income and 94% of export revenues.

Oil is Nigeria’s main source of foreign exchange earnings and government financing, accounting for 11% of total GDP, 70% of government income and 94% of export revenues.

But in Q2 2016, Nigeria entered its first technical recession since 2004.

The country’s economy has taken a massive hit from a 17% dive in income from the oil sector from a year earlier and in recent months Nigeria has lost its crown to Angola as the biggest African oil producer.

Meanwhile a steep drop in its currency has seen it trading places with South Africa as the continent’s largest economy. The crash in oil prices is not the only reason for the slump.

Political and security challenges, such as the extremist Islamist insurgency group Boko Haram, which has claimed about 20,000 lives and created 1.5m refugees, do not look set to end soon.

TURKEY

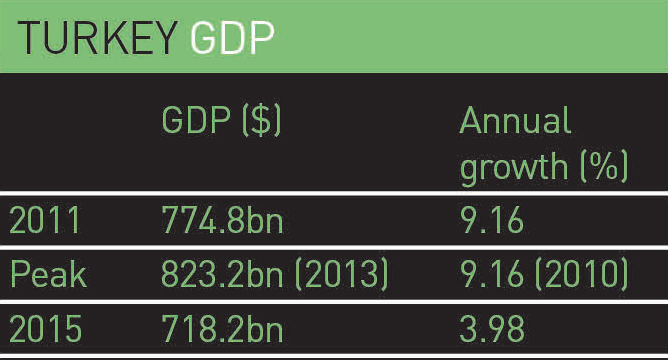

For 10 years after Recep Tayyip Erdogan came to power in 2003, Turkey enjoyed strong, non-inflationary growth.

For 10 years after Recep Tayyip Erdogan came to power in 2003, Turkey enjoyed strong, non-inflationary growth.

In 2010 its economy grew at 9.16%, making it the third-fastest growing economy in the world.

Construction was largely behind the growth, accounting for 6% of GDP, but with the related industries – steel, timber and energy – it totals 30%.

And over the past 15 years Turkey has become a supplier of high-quality consumer goods. It is now Europe’s biggest manufacturer of television sets and light commercial vehicles.

But by the end of 2014, the IMF said that Turkey “can only sustain high growth at the expense of growing external imbalances”. GDP growth was 3.02% and the following year the pace had only marginally quickened to 3.98%.

Europe makes up 60% of Turkey’s export market as well as 75% of its foreign direct investment. As Europe’s economies stumble, so does Turkey’s. Add to that political factors that threaten stability and its economic outlook becomes uncertain.

Ease of doing business: World Bank ranking

1. SINGAPORE

2. NEW ZEALAND

3. DENMARK

4. SOUTH KOREA

5. HONG KONG SAR,CHINA

116. BRAZIL

51. RUSSIA

130. INDIA

84. CHINA

38. MEXICO

109. INDONESIA

169. NIGERIA

55. TURKEY

Time to rethink success

There is an argument for changing the way that successful countries are measured, according to Ruchir Sharma, head of emerging markets and chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

Instead of using GDP growth as a typical economic indicator in today’s post-financial crisis world, Sharma believes a new set of indicators is needed. Every region in the world has suffered a slowdown since 2008, and 2016 marks the seventh year of the weakest global economic expansion cycle in modern history.

He has devised an alternative 10-rule system for measuring success, which is outlined in his book The Rise and Fall of Nations.

These include looking at the number of billionaires within a country and identifying the “good” and the “bad”. “Good” billionaires – think Bill Gates and Elon Musk – create jobs and products that support economic growth. “Bad” billionaires, says Sharma, have the political contacts to make their fortunes, often corruptly, in industries such as oil, gas, mining or construction.

Countries where private debt has been growing much faster than the economy for five years should be put on watch for a serious slowdown.

And recognition that not all investment binges are equal is advised. Bad spending is usually triggered by investors rushing to capitalise on spiking prices for a coveted asset, such as housing. While not necessarily a bad thing, he says, the best kinds of investment binge involve spending on manufacturing or technology, which will boost productivity when the economy recovers.