The British Property Federation is seeking a clear definition of what constitutes a microflat, as the model becomes an increasingly important method of housing provision.

Advocates of microliving – any flat below minimum space guidelines of 37 sq m – say it is a necessary tool for solving the housing crisis. But policymakers remain sceptical of anything that could create new blocks of slums and bedsits.

The BPF, which has come out neither for or against microflats, commissioned JLL to look at the models on offer so far, in order to arrive at some useful definitions.

Microflats: one example

U+I has launched a new microflat product that it hopes to develop in its thousands to help the “squeezed middle” living in the centre of London.

Dubbed Town Flats, the compact flats come as small as 19 sq m – half the 37 sq m required by planning guidance – but use efficient storage and design to feel larger.

The 19 sq m apartment is half the size of the 37 sq m recommended in London guidelines. Click on the images and move your mouse to pan around the room

The 24 sq m apartment could command rents of up to £1,100 per month. Click on the images and move your mouse to pan around the room

The bathroom in the 19 sq m apartment. Click on the images and move your mouse to pan around the room

A view of the 19 sq m apartment from the “bedroom”. Click on the images and move your mouse to pan around the room

“What role could microliving play in the housing crisis? The important thing at this stage is to define what we mean by that, to allow a sensible discussion,” says Nick Whitten, director in JLL’s research team.

“We have a UK housing crisis defined by a systemic failure to build enough homes for the population. One obvious solution is to find ways to increase the variety of tenures and different products. That has to be a sensible way to increase housing options.”

The three types

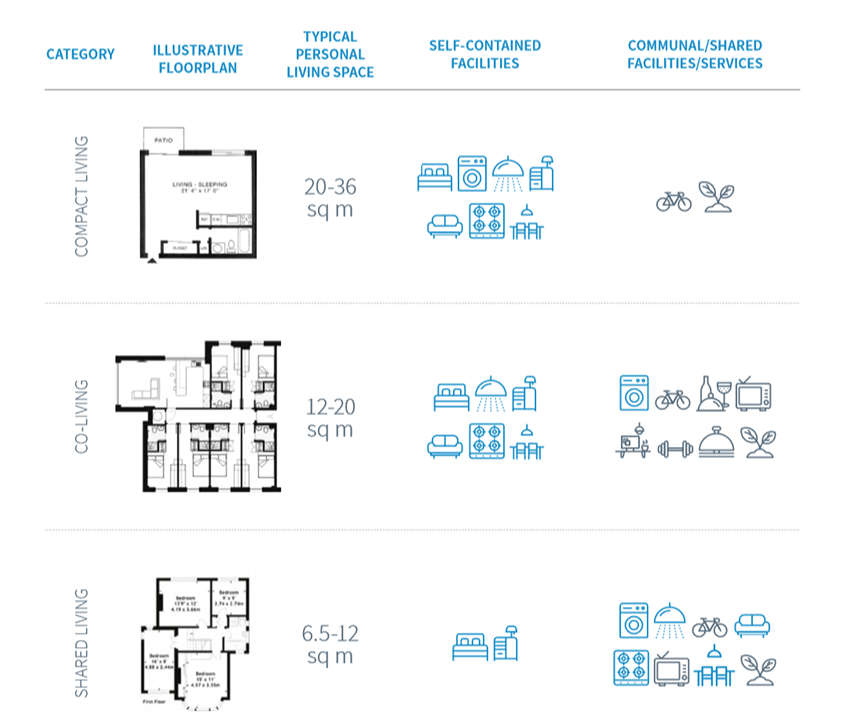

The research, which looked at 62 schemes around the world, has found three types of microliving product types evolving:

■ compact living: self-contained smaller homes;

■ co-living: purpose-built and managed developments that provide both personal and shared amenity space; and

■ shared living: converted or subdivided houses or HMOs.

A number of UK developers have come out in support of such schemes, with both Dolphin and Pocket building blocks of smaller flats around London, while U+I has taken this a step further by mocking up two microapartments in its offices in Victoria that were just 19 sq m at their smallest.

Co-living developer the Collective has, meanwhile, grabbed headlines for its blocks in Old Oak Common.

No reduction in guidelines

The GLA, which is the only authority in the country to actually deploy a minimum space standard, has stated repeatedly that it would not reduce space guidelines.

Jules Pipe, London’s deputy mayor for planning, said a month before the Draft London Plan was released that it would include “a number of policies on housing design, and places a strong emphasis on ensuring minimum space standards are met or exceeded. We are not going to a race to the bottom.”

However, the plan did eventually include three pages referring to co-living and shared living under what it describes as the suis generis use class, with the inference being that although policy makers did not like microflats there does needed to be a discussion about what is emerging.

The plan stated: “Development proposals for such schemes should be supported where only they meet an identified market need.”

The BPF research says: “The lack of a common definition creates misunderstandings between the key parties involved in housing delivery. This slows productivity and potentially hinders the viability of proposed new housing schemes.”

Re-urbanisation

The argument for smaller flats is that many cities are undergoing a housing shortage owing to re-urbanisation, so people should be able to choose between cheaper and better-located, but smaller, flats if they wish. The problem for regulatory authorities is that relaxing laws on design and space can lead to abuses of the system.

The UK is not alone with its housing crisis, and many cities around the world are seeing a trend towards re-urbanisation, which puts pressure available space. As a result, a number of cities are looking at microliving and co-living schemes and how best to regulate them.

The research looked at schemes including the 500-home Change=Nieuw West in Amsterdam, which has a unit size of 30 sq m; the 55-flat Carme Place in New York, where units were as small as 24 sq m; and iApartment in Frankfurt, which provides 70 flats of around 25 sq m.

Technology and good design can improve schemes.

“Where there is political understanding, there is an onus on design quality and technological solutions to provide good-quality smaller housing,” says Whitten.

He adds: “The point being that what we need for a home has changed since planning regulations were constructed.”

See also: Co-living: will developers achieve the impossible?

To send feedback, e-mail alex.peace@egi.co.uk or tweet @egalexpeace or @estatesgazette