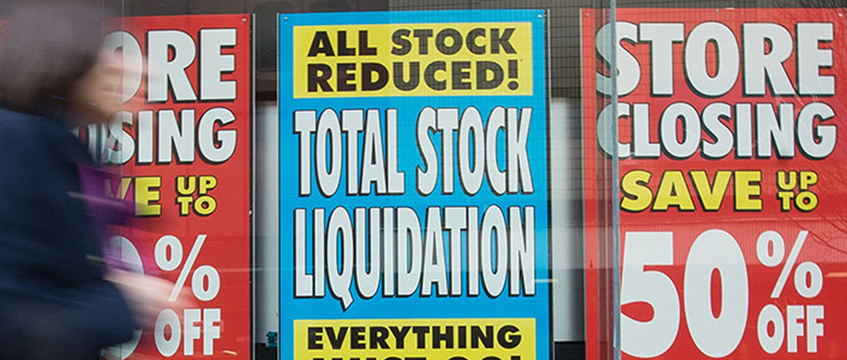

COMMENT: The problems on the country’s high streets need no introduction, and the bad news keeps coming.

The latest news is that Columbia Threadneedle has put a shopping centre in Kirkcaldy, Fife, up for auction with a reserve of just £1, reflecting a gross initial yield of 15,590,500%. It shows how investors in retail risk losing their entire investments.

In response to the general woe, the government has announced the launch of its £650m Future High Streets Fund to support local areas and help councils make their high streets and town centres fit for the future. This is on top of the cut by one-third in rates for small retailers announced in the Autumn Budget.

For some places, however, it is simply too late. Councils need to allow wholesale regeneration and changes of use. Town centres must face up to the experiences that villages went through in the last century as many of their shops closed.

In other places, retail still thrives. Walk down Marylebone High Street or Regent Street in central London, or through a Westfield shopping centre. Here, people of all ages come to shop, for leisure, to linger and to be entertained.

A single owner

The common theme here is unity of ownership. Control by one party enables investments to be made, services in the public realm to be provided and a suitable mix of shops, food and beverage, and other uses to be achieved and managed.

Contrast that with so many of our high streets – with multiple ownerships, different landlords competing for the last few tenants in a downward spiral and with little money being available to invest in creating a destination. As a result, high streets increasingly become places where people do not want to be, and so the decline continues. Without unity of ownership, it will be difficult for investments by local authorities to yield long-term results, and rates relief will do little to arrest the decline.

One way to achieve unity of ownership will be for local authorities to acquire all the properties in their high streets. In some places this is happening – for example, Winchester City Council has been acquiring shops on its high street needed for its Central Winchester Regeneration project.

Acquisitive vehicle

However, many councils will not have the money or the risk appetite for this. Here, another approach is needed. The value of the high street combined should be greater than the sum of the individual units, given the increased opportunities for control, investment and management. In this situation, an alternative could be for the council to set up a vehicle to acquire all relevant interests, subject to the existing occupational leases.

Owners would be given a stake in the new vehicle equal to the value of their investment, perhaps with a share in the uplift to sweeten the arrangement. Any remaining uplift in value could be retained by the council as its own stake or be used to fund improvements.

This would achieve unity of ownership without the need for councils to invest sums in land acquisition. Investors would now have a share in a more diversified investment, rather than being focused on single units. This share could be freely traded, including in smaller chunks, creating a more liquid market for investments and ultimately a wider pool of investors to be reached.

The vehicle could then appoint a manager to run the whole high street for the benefit of the investors and the wider community. This would allow it to carry out public realm works, improve the retail mix and create an attractive destination. Excess retail could be adapted for different uses. An estate service charge could be levied.

This approach would need a change in the law to allow the necessary powers to be granted and exercised if agreement could not be reached among all stakeholders. It would not suit every location, but where it might work it could allow high streets to be transformed. That government fund could then be used to help pay for improvements that have a chance of being put to genuine long-term effective use.

Investors should get a better and safer return – perhaps not a 15,590,500% yield, but much better than risking losing everything. And, over time, localities would have a reinvigorated destination at their hearts.

Hugh Lumby is head of global real estate at Ashurst LLP. He is also co-chair of the Urban Land Institute’s European Urban Regeneration Council and an elected member of Winchester City Council.