At the Property Litigation Association’s annual Alan Langleben Memorial Essay Competition Philip Sheppard won first prize with this entry on the assured tenancy regime relating to long leaseholds.

Leasehold dwellings comprise nearly a fifth of England’s housing stock and more than 40% of new homes are of leasehold tenure. The average long leasehold home currently costs around £260,000. They are capital investments and long-term homes.

Parliament, courts and regulators have between them seen fit to establish safeguards to protect long residential leaseholds from being seized or snuffed out too easily by landlords or creditors.

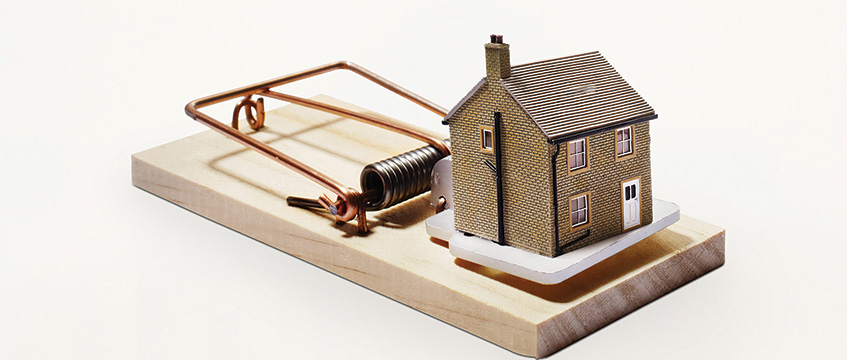

Unfortunately, these measures are undermined by a loophole in the assured tenancy regime, which leaves long leaseholds vulnerable to peremptory termination, without remedy or relief for the dispossessed occupier.

The loophole

If an assured tenancy contains re-entry provisions, a landlord can seek possession for rent arrears under section 7 and Ground 8 of Schedule 2 to the Housing Act 1988.

If rent arrears reach a prescribed threshold, a landlord can serve notice on a tenant requiring them to pay the arrears. On expiry of the notice, the landlord can issue a claim for possession. If the rent arrears remain unpaid at the hearing, then the landlord will be entitled to possession, without more (section 7).

This procedure is designed to bring rack-rent tenancies to an end in circumstances in which the tenant is unlikely to have any long-term interest in the property. It was never designed to be used in the case of long leasehold interests.

Indeed, long leaseholds have until now generally fallen outside the assured tenancy regime because of their typically low rents. Leases with annual rents of less than £250 a year (or £1,000 in London) cannot be assured tenancies.

However, the average ground rent now stands at over £300 per year and is increasing at a rate of 5% per year. The prospect of challenging an escalating ground rent has been curtailed following Arnold v Britton [2015] UKSC 36; [2015] EGLR 53 and escalating ground rents are now an increasingly lucrative investment opportunity.

Despite this, the rent thresholds set out in the Housing Act 1988 have not risen in the past 30 years. As a result, long leasehold interests are now increasingly likely to be assured tenancies and increasingly vulnerable to an inappropriate termination regime.

The Ground 8 regime

The consequences for long leaseholders of the Ground 8 regime can best be seen by considering each step of the process and comparing it with similar regimes.

1. The rent arrears threshold

In the case of a rent payable annually, a landlord is entitled to possession if three months’ rent is in arrears by at least three months. Lower thresholds exist for rents paid more frequently. Given the low levels of rent required to engage the assured tenancy regime, a landlord may therefore be entitled to bring a long leasehold to an end for arrears of as little as £62.50. In no other circumstance could so small a debt invite such disproportionate consequences.

2. Pre-action

The landlord is required to give the leaseholder two weeks’ notice before commencing proceedings (section 8 of the 1988 Act). There is no pre-action protocol and no requirement for the landlord to act reasonably. The landlord is not required to consider proposals put forward by the leaseholder, nor delay proceedings so that the leaseholder can raise funds. A landlord may even seek possession while the leaseholder is taking active steps to sell the property (something which District Judge Gaunt described as “troubling” in Richardson v Midland Heart Ltd [2008] PLSCS 205).

This fails to recognise that long leaseholders have often paid a very high premium in exchange for a long tenure and have an expectation that their interest will not be terminated quickly or for trivial breaches. Given the potential consequences for the leaseholder, it is unjust that a landlord can act both precipitately and capriciously.

This differs markedly to possession claims for mortgage arrears. Mortgagees are expected to comply with the relevant pre-action protocol and may also be required to comply with the FCA Conduct of Business Sourcebook, both of which are intended to encourage co-operation and discourage premature repossession. If mortgagors do not comply with these standards, then the court is likely to adjourn proceedings until all other options have been exhausted.

3. The hearing and the order

If the arrears are above the threshold when notice was served and are still above the threshold on the day of the hearing, the landlord is entitled to an order for possession (section 7(3)). The court has no discretion to refuse the order. The court has only limited power to adjourn the hearing to allow the tenant time to pay the arrears.

In North British Housing Association Ltd v Matthews [2004] EWCA Civ 1736 it was held that the court may adjourn only in “exceptional circumstances” where refusal would be “outrageously unjust”. The examples accepted by the Court of Appeal (of being mugged on the way to court with the rent, or of a computer glitch preventing payment until after the hearing) set a high bar. This offers little comfort to long leaseholders, whose circumstances may be unfortunate but in no way exceptional.

Once made, the order must take effect within two weeks (or six weeks in the case of exceptional hardship). There is no discretion to postpone enforcement beyond this point. This does not allow the court the discretion to do justice on the particular facts or to avoid a disproportionate order from being made.

This contrasts unfavourably with claims brought by mortgagees for possession, or by landlords in claims for forfeiture. In both cases, the statutory time limit does not apply, and a court has the inherent jurisdiction to postpone enforcement (section 89(2)(a) and (b)). In the case of claims by mortgagees, section 36 of the Administration of Justice Act 1970 allows a court to adjourn or suspend an order where the mortgagor will be able to settle the arrears by selling the property or by amortising the debt over the remaining mortgage term. In both cases, therefore, the court has the discretion to reach a just outcome. No such discretion is afforded the court (or leaseholder) in a Ground 8 case.

4. Enforcement and relief

Once the order is enforced, the leaseholder’s capital asset is extinguished entirely. Chargees lose their security. Neither has any claim for relief, even if the arrears are later paid and the landlord is fully compensated. Meanwhile, the landlord receives a windfall – an unencumbered property – the value of which will far exceed the level of arrears.

On the other hand, if a mortgagee exercises a power of sale following possession, the mortgagor’s capital asset is not extinguished; the proceeds of sale are applied to discharge the debt and any surplus returned to the mortgagor. The mortgagee does not receive a windfall

nor the mortgagor a disproportionate loss.

Alternatively, if a landlord forfeits a long leasehold, then both the leaseholder and any chargees will be entitled to apply for relief. The County Court must grant relief and reinstate the lease if the leaseholder pays the arrears and the costs of the action before the date of possession (section 138(3) of the County Courts Act 1984), and both the County Court and High Court have discretion to grant relief after enforcement of the possession order (section 138(9A) of the 1984 Act and section 210 of the Common Law Procedure Act 1852). In exceptional circumstances relief can even be obtained if the arrears remain unpaid (again at the court’s discretion).

If the court is asked to exercise its discretion, it will take into account all the circumstances of the case, including the leaseholder’s conduct and culpability, the impact on the landlord, and the “windfall effect” of refusing to grant relief. This allows the court to undertake a more nuanced analysis and to reach a conclusion that is just and fair. It also allows leaseholders time which they may not otherwise have had to remedy their earlier breach. Such an approach is far beyond the scope of the Ground 8 regime.

In closing

The Ground 8 regime is a blunt tool which was neither intended nor drafted to be used against long leasehold tenures. It encourages landlords to act precipitately and without compromise. It gives no allowance to circumstances or to vulnerability of leaseholders. It forces courts to deliver, without discretion, judgments that are both life-changing and disproportionate to the breach they are intended to address. It contains none of the safeguards deemed essential to the application of other regimes which would effectively terminate the rights of long leasehold homeowners.

There is yet hope. The government has proposed reforms to close the Ground 8 loophole, by capping ground rents, limiting rent reviews, and excluding long leaseholds from the assured tenancy regime. Legislation is expected in 2020. In the meantime, leaseholders will have to remain vigilant and make do with this unjust law for just a little longer.

Main image © Mood Board/Rex/Shutterstock

Read the runner-up entries at www.egi.co.uk/legal/

Philip Sheppard is a property litigation solicitor at Veale Wasbrough Vizards