James Driscoll and Oliver French discuss a recent case which highlights that where relativity is an issue, economic evidence should be supported by valuation evidence

A common area of disagreement in enfranchisement claims relates to how to measure and apply “relativity”.

Relativity may be defined as the proportion of the value of the freehold (with vacant possession) that the value of the current lease bears to it. It is expressed as a percentage.

For example, an unexpired term of 50 years would generally be considered to have a relativity of approximately 75% of the freehold value. The longer the current lease, the higher the relativity would be. Conversely, the shorter the lease, the lower the relativity.

The importance of relativity

Relativity is used to calculate the “marriage value” (that is, the value that is released with the coalescence of the existing interests) in enfranchisement claims. For example, using approximate figures, if an existing lease value is £750,000 and the landlord’s existing freehold interest is £100,000, the sum of the existing interest is £850,000. If the freehold vacant possession value is £1,000,000, this gives a marriage value of £150,000.

Under the legislation, the existing lease value, and therefore the relativity, must be based on the assumption that the subject property does not benefit from the statutory rights contained in the legislation. This causes difficulties for valuers, as market evidence of such a hypothetical situation (that is, a property without statutory rights) is extremely rare.

Be cautious of market evidence

There are obvious problems in using market sales evidence as it is affected (or tainted) by the fact that purchasers are bargaining in the knowledge that a leaseholder has important statutory rights. The prices would be different if these statutory rights did not exist.

Assessing the appropriate relativity is not easy. If market sales evidence is unsuitable, how else can the current value of the lease, by comparison to what price the freehold would command if sold with vacant possession, be worked out?

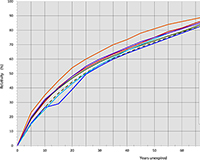

The established mechanism is by using the “graphs of relativity”. A number of organisations publish tables or graphs that aim to show the relative value of a lease according to its unexpired term, based on the statutory assumption. These graphs are based on the experience of the organisation’s market transactions, settlements they have been involved in (or are aware of), their professional opinions and, in some cases, by examining past decisions of the leasehold valuation tribunal (“LVT”), now the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber).

Graphs of relativity

While the use of these graphs is widespread, their use is not without its critics.

In the leading decision Nailrile Ltd v Earl Cadogan [2009] 2 EGLR 151, the Upper Tribunal (“UT”) stated that relativity is best assessed by utilising any available evidence of transactions and by considering the published relativity graphs. An attempt was made by a RICS working party of valuers (chaired by Jonathan Gaunt QC) to arrive at a consensus on the graphs. Despite their efforts it proved to be impossible for them to agree on a single definitive graph that could be used as evidence (see the RICS’ Graphs of Relativity, 2009). They did, however, express hope that the report would provide useful guidance to practitioners.

In proceedings where relativity is in issue, it is common practice for each side to call expert valuation evidence, leaving it to the tribunal to reach a decision on the basis of this evidence and possibly also the member’s professional knowledge and experience.

“Hedonic regression”

In Kosta v Trustees of the Phillimore Estate [2014] UKUT 0319 (LC); [2014] PLSCS 242 there was a radical departure from this practice, when a leaseholder making an enfranchisement claim for a house (under the Leasehold Reform Act 1967) called an economist to give evidence on relativity (a valuer was also called but he confined his evidence to factual matters and he did not offer an independent expert opinion).

The economist was Dr Bracke, then of the London School of Economics, who has made a study of the London property market by focusing on sales in central London during the period January 1987 to December 1991. His study aimed to analyse sales of properties that were unenfranchiseable and to exclude any properties which, at the time, would have been enfranchiseable under the 1967 Act (leasehold flats did not acquire enfranchisement rights until the Leasehold Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993, which also removed the remaining upper value qualification for houses).

In the course of his research he applied a statistical analysis method called “hedonic regression” to a large volume of data (obtained from two private organisations) in order to devise a model that produced estimates of relativity for different lease lengths. In all, he studied data from some 8,000 sales of properties which had, at the time, no statutory rights.

Having been instructed to advise the leaseholder, he proposed to the LVT in 2013 a relativity of 87.04%, which was far higher than the 75.5% proposed on behalf of the landlord. The LVT determined a relativity of 76%. It determined the freehold vacant possession value at £16,138.743, which the parties did not challenge on appeal. The unexpired term of the house lease when the enfranchisement notice was given (in October 2011) was 52.45 years.

The landlord’s evidence was based on the graphs, as it could not locate any relevant market evidence to assist in arriving at a conclusion. The LVT was highly critical of the approach taken by the leaseholder on relativity.

The appeal

In the ensuing appeal, the leaseholder again called Dr Bracke to give evidence on relativity but, again, a qualified valuer was not called to offer an expert opinion.

In the UT, much time was spent considering the quality of Dr Bracke’s research and his partiality, given that he has invested in a company (Parthenia Research Limited) to market the results of his research. Although the UT accepted that in principle the research appeared to be academically sound, it noted that the evidence was not supported by evidence from a valuer. By contrast, the landlord called valuation evidence and academic evidence from Professor Lizieri of Cambridge University.

Dismissing the appeal, the UT, having evaluated Dr Bracke’s evidence (in light of his evidence and that of Professor Lizieri), made a number of “micro” criticisms which in the UT’s view could not be satisfactorily dealt with within the evidence. They concluded that, although he was an impressive and an unbiased witness, it could not place any weight on his evidence in this case.

It noted that no valuation evidence was submitted on behalf of the leaseholder to explain and to support the two key components of his research: (a) has he produced reliable quantitative evidence for relativities for the market between 1987 and 1993; and (b) did this evidence give reliable guidance on relativity for calculating the existing lease value of the property at the valuation date in October 2011 on the statutory assumptions?

Instead, the UT based its decision on the evidence on the graphs despite the shortcomings, as it saw it, of this evidence. It reasoned that a potential purchaser who sought advice from an experienced valuer would inevitably be influenced by such guidance as the graphs can give. Dr Bracke’s evidence produced radically different conclusions from the evidence available from the graphs that professionals have relied on for many years.

Furthermore, the UT accepted that the statutory assumption to value the property as at the valuation date does have a significantly negative impact on value as it “…must be assumed to be offered for sale without Act rights in circumstances where other leasehold properties were being offered for sale with Act rights” [129].

Source the valuation evidence

The UT noted that it, LVTs and the profession have so far been unsuccessful “… in finding a settled position on relativities for leasehold properties” [143].

In future cases where relativity is in issue, such economic evidence should at least be supported by valuation evidence.

Professor James Driscoll is a solicitor and a writer and Oliver French is a chartered valuation surveyor at Savills