The two principal tax considerations when structuring BTR transactions are value added tax (VAT) and land and buildings transaction tax (LBTT).

VAT

First, a couple of preliminary words about terminology. When we refer to “output tax”, we mean VAT in respect of supplies of goods or services made by a taxpayer. Taxpayers have a statutory obligation to account for output tax to HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC). When we refer to “input tax”, we mean VAT charged in respect of supplies of goods or services made to a taxpayer. Contracts often provide for input tax to be paid to suppliers in addition to the consideration for the supplies in question. It may be possible for taxpayers to set off input tax against their liability to account for output tax and, where input tax exceeds output tax, taxpayers can sometimes recover the excess of input tax from HMRC. The circumstances in which credit can be obtained for input tax are considered below.

When structuring a BTR project, the main objectives in relation to VAT are to minimise the extent to which input tax is incurred and maximise the extent to which it can be recovered. How much input tax a taxpayer can recover depends on the nature of the outputs that a taxpayer makes with the inputs in question. Where the taxpayer makes VAT-exempt outputs, no input tax can be recovered, while if wholly taxable outputs are made, generally all the associated input tax can be recovered. (Where a mix of exempt and taxable outputs is made, a proportion of the input tax can be recovered – a situation known as “partial exemption”.)

The basic rule is that supplies of UK land are exempt, so associated input tax would be irrecoverable. With commercial developments, this difficulty is often overcome by exercising the “option to tax”, under which a taxpayer can elect to make taxable supplies (standard rated at 20%) with the property and so recover any associated input tax. However, when the option to tax is exercised over a building designed as a dwelling or a number of dwellings, each time a grant is made with the building, the option to tax is effectively disapplied and the grants made remain exempt, with the effect that no input tax can be recovered.

There is, however, another form of supply that can be made with dwellings – the “zero-rated” supply. While there is no obligation to account for output tax on zero‑rated supplies, as VAT is charged at a zero rate, it is a taxable supply and associated input tax can be recovered.

The making of such a zero‑rated supply by the entity incurring the development costs forms the cornerstone of most BTR projects. Briefly, a zero-rated supply can be made when a taxpayer makes the first grant of a major interest in a building designed as a number of dwellings and that taxpayer is the person constructing the dwellings. This can involve an “Opco/Propco” structure, where Propco incurs the development costs before granting a zero-rated long lease to Opco (often a subsidiary of Propco), with Opco then making the short-term occupational lets.

Alternatively, a forward-funding structure can be used, where a developer/vendor makes a zero-rated sale to a funder/buyer, by selling the property after construction has reached the stage of the first brick course above the foundations (“golden brick” stage).

In both types of transaction, the party incurring the development costs can also reduce the input tax that it incurs in the first place, as construction services (usually standard rated) supplied in the course of constructing dwellings are also zero-rated, so reducing financing costs.

LBTT

LBTT is a significant cost to BTR projects and the first consideration here is to ensure that LBTT is not suffered on the development costs. This is usually achieved by maintaining separation between the purchase missives and the development contract. Revenue Scotland has confirmed that, where this is done properly, it will follow the rule in Prudential Assurance Company Ltd v Inland Revenue Commissioners 1992 STC 863, that only the value of the land at sale falls into tax. (Structuring a transaction in this way is often referred to as “Prudential planning”.)

Consideration should also be given to LBTT multiple dwellings relief (MDR). MDR operates by setting the applicable residential rate of LBTT by reference to the average consideration for each dwelling, rather than by reference to the aggregate consideration. Before claiming MDR, a comparison should be made with the charge levied on the aggregate consideration at the (lower) commercial rates (applicable where six or more dwellings are purchased).

Lastly on LBTT, it should be noted that, in contrast to the position for properties in England and Wales subject to stamp duty land tax, the 3% additional dwelling supplement does not apply where six or more dwellings are purchased.

Image © Rex/Shutterstock

Jim Hillan is a tax partner at CMS and Simon Johnston is a partner in the banking and finance group at CMS.

Build-to-rent and lending

Many of the lending issues for a BTR development will be familiar to those experienced with lending on commercial real estate developments. For instance, it is important for lenders to be satisfied in relation to real estate due diligence, planning and the building contract package, writes Simon Johnston.

The Loan Market Association (LMA) form of facility agreement for real estate finance development transactions will often be a useful starting point, dealing as it does with such concepts, together with requiring the “budgeted costs” for the carrying out of the development to be delivered as a condition precedent, and providing a framework for related issues such as cost overruns and cost savings. However, there will be additional areas that will need to be considered.

Plan for success

In terms of financial covenants, historical interest cover and projected interest cover in a commercial real estate context, compare net rental income (after deducting service charge, void costs and VAT) with the finance charges payable.

Thought needs to be given as to how to calculate net rental income in a PRS context, where tenants simply pay a gross rent and it is for the owner to deal with operating expenses and maintenance and insurance. Lenders need to consider the gross to net calculation and ensure that it is monitored and reported appropriately. They may also need to allow greater access to the rental income to their borrowers, to enable those borrowers to meet the necessary costs of running the property on a day-to-day basis.

Appropriate tax structuring is fundamental to a BTR scheme being effective. It is also important in giving the optionality, which a number of lenders find attractive, to sell individual residential units in the event that the letting business is not as successful as anticipated. Many lenders will require a tax structuring paper, dealing with the VAT position and ensuring recoverability of VAT or the ability to charge (and be charged) on a zero-rated basis, to be delivered as a condition precedent to any loans being advanced.

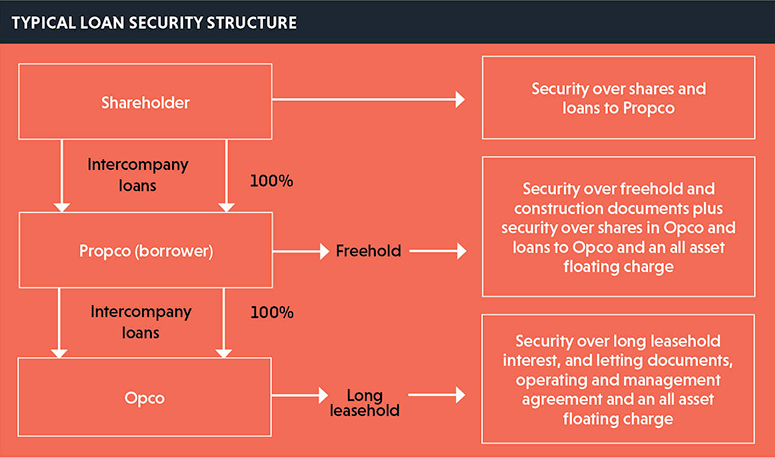

When it comes to security, lenders typically take a “belt and braces” approach, with security being taken over the shares in each relevant company, together with security over any intercompany loans made to each relevant company, as well as all asset security being taken in respect of each relevant company. The typical structure that might be expected is shown in the diagram below.

In a typical commercial real estate transaction, senior lenders will often view the asset security (ie over the real estate, construction documentation, rental income, etc) as their primary security and their more likely enforcement route, with security over the shares and other equity interests as providing optionality, via the potential of a different enforcement approach.

Issues can arise

However, in the BTR context there is potential for VAT issues under the capital goods scheme to arise on a sale of the real estate interests, and the potential to trigger LBTT payable on an assignment of the Opco lease or a sale of Opco separately from Propco at the rate applicable to a new grant of the lease, rather than at the rate applicable to an assignment of the lease.

In addition, in an England and Wales context, a real estate sale may trigger rights of first refusal if there are qualifying tenancies (which could arise on a partial sale of units or indeed if some of the flats are tenancies in the form of corporate lets rather than assured shorthold tenancies). For those reasons, lenders may place more importance on being able to effect a corporate sale of Propco (which will include all of Propco’s assets, eg the freehold title and its ownership of Opco and intercompany loans owing to it by Opco) than in a typical commercial real estate financing.