Following the government announcing its support for a third runway at Heathrow Airport, Martha Grekos takes an in-depth look at the complicated process of final approval and the potential timeline for delivery

The political sclerosis of airport expansion seems to have finally gained some pace, as the government has at last announced its backing for a third runway at Heathrow. In addition, Heathrow and the secretary of state have entered into a non-legally binding “Statement of Principles” on which they intend to proceed so as to facilitate the implementation and development of the airport.

So what needs to happen next in order for Heathrow to get the runway up and running?

National policy statement

First of all, there is a need for an Airports National Policy Statement (NPS). This will confirm the need for a new runway; identify the suitable location(s) in order to provide a clear framework for investment and planning decisions; and state circumstances where it would be particularly important to address the adverse impacts of development. The NPS would undergo a democratic process of public consultation, strategic environmental assessment and parliamentary scrutiny before being designated (ie published). It would provide the framework within which the Planning Inspectorate (PINS) makes its recommendations to the secretary of state.

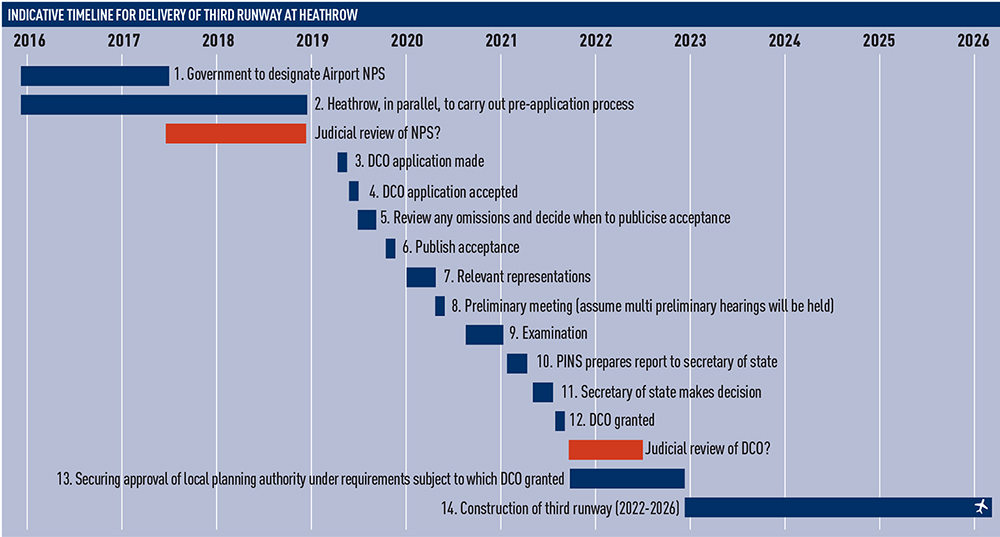

There is currently no Airports NPS. It is feasible that an NPS could be designated within two years from the government’s announcement to back Heathrow, if there were no legal challenges to the designation process. The Statement of Principles has “no later than 31 July 2017” as a key delivery milestone for the NPS.

Development consent order (DCO)

Once an Airports NPS has been designated, Heathrow will need to make its DCO application to PINS. The DCO regime has been specifically designed to deal with nationally significant infrastructure schemes of this type and their “associated development”. The procedure is de-politicised. The management of the application and the examination process rests with PINS and the final decision would be in the hands of the secretary of state.

However, the DCO application and decision-making process is heavily regulated, involving prescribed pre-application consultation procedures and tight timescales, including a short window of 28 days for acceptance of the application and six months for examination, with no extension allowed (see the Thames Tideway Tunnel DCO). PINS then has three months to write its report and the secretary of state has another three months to consider that report before issuing the final decision.

It is also front-loaded. Depending on the size and complexity of the project, it can take two to three years to carry out the – pre-application consultation requirements with the public and other interested groups (see the Hinkley Point C DCO). The third runway at Heathrow is likely to take just as long given the considerable amount of work that will have to go into preparing the application.

The Planning Act 2008 (the 2008 Act) disapplies some, but not all, consents under other enactments, replacing them with equivalent controls (say, listed building consent) that are dealt with as part of the DCO application. Also, consents prescribed by the secretary of state – for example, consents under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 – can only be removed with the consent of that body which has the function of granting the prescribed consent. Promotion of airport expansion would include a suite of consents that would need to be dealt with by other bodies, and the implementation of such a project would depend on those consents being obtained.

The saving grace for Heathrow is that the need for the new runway will have to be taken as decided at examination as this would have been established through the NPS and cannot be questioned during the DCO process. However, Heathrow will have to meet the criteria set by the NPS in order for the DCO to be obtained, subject to the limitation in the 2008 Act that states that “the adverse impact of the proposed development would outweigh its benefits”.

Depending on whether Heathrow decides to begin the pre-application process in parallel with the government progressing the designation of an NPS, it could mean that a DCO is not obtained until 2020/2021 at the earliest. The Statement of Principles states that Heathrow aims to submit a DCO application by March 2020, with a view to gaining consent by September 2021.

Special parliamentary procedure

Regardless of the modifications made by the Growth and Infrastructure Act 2013 to the special parliamentary procedure (SPP) in the 2008 Act, the SPP still applies to the compulsory acquisition of/right over National Trust land, common land, open spaces or fuel or field garden allotments. These provisions cannot be disapplied by a DCO.

Some further modifications, however, extend the situations in which SPP is not required. If Heathrow proposes to provide land of equal value to that which is to be lost as a result of the scheme, the secretary of state can issue a certificate, in which case SPP is not triggered. Under the new law, the secretary of state can also issue a certificate if there is no suitable exchange land available at reasonable cost and if it is in the public interest for development to start sooner than would be the case if the land were subject to SPP.

This means that if Heathrow proposes to compulsorily purchase any such land, then the best outcome would be for the secretary of state to issue a certificate. Otherwise, after the examination has finished, the DCO will have to be referred to parliament for a second process of scrutiny, including an opportunity for people to petition parliament that the DCO should not be made. The Growth and Infrastructure Act 2013 removes the possibility that any application which is subject to SPP can be revisited in full in parliament – only the issues which triggered SPP can be considered.

Judicial review

Both the airport and the secretary of state acknowledge that third party support will be critical to meeting the key programming milestones. There are many opportunities for legal challenge by way of judicial review at each step of the administrative process, including the designation of the NPS as well once the DCO process is concluded.

Opponents will have a six-week window in which to mount a challenge through the judicial review process. Four local authorities – Windsor and Maidenhead, Hillingdon, Richmond, and Wandsworth – have pledged to fight the expansion. Greenpeace has joined this “alliance” and other bodies likely to challenge the decision include residents’ organisation Teddington Action Group and activist lawyers Client Earth.

Any challenge is likely to be progressed quickly. The six-week window is non-extendable and the Planning Court in the High Court will hold the final hearing of a judicial review within six months. Of course, courts, including the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court, can move quickly if required, as they did with the Thames Tideway Tunnel judicial review. Permission to bring judicial review proceedings on that project was refused at an oral hearing within three months of the four cases being brought.

It is likely that only after a further year or more following the DCO will all the legal challenges be exhausted, ie 2022 at the earliest.

Requirements

Once a DCO is made, the requirements have to be discharged by the local planning authority, which still retains an element of control over the project. In addition, the process for changing a DCO differs depending on when that change is proposed (before or after the DCO is made) and whether the change is considered to be “material” or “non-material”, which is not always clear-cut.

Subject to any changes being sought by Heathrow and all the requirements for commencement having been discharged (securing such approvals could take anything from a few months to a year), the construction of the runway could then begin in 2022. If, as anticipated, it will take between four and five years to construct a third runway, it is unlikely for us to see any planes taking off before 2026 at the earliest.

Brexit

The fear which surrounds Britain’s exit from the EU has cast some uncertainty over the country’s place on the global stage. The expansion of Heathrow is hailed by some as a way of ensuring Britain remains a hub of activity and business. It will be very interesting to see how all this plays out with the ongoing issues over a “hard” or “soft” Brexit; the government’s non-compliance with the EU Air Quality Directive; as well as the extent to which UK environmental laws are underpinned by EU legislation over the coming years.

Martha Grekos is a partner and head of planning at Howard Kennedy LLP