Section 9(1A)(d) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967 is often described as a counter-factual deeming provision for the valuation of the freeholder’s interest in a house and premises on enfranchisement. It requires the price payable for that interest to be diminished by the extent to which its value had been increased by improvements carried out by the tenant, or their predecessor in title, at their own expense. The Court of Appeal in Alberti v Cadogan Holdings Ltd [2022] EWCA Civ 499; [2022] PLSCS 64 was asked to determine the correct interpretation of section 9(1A)(d) and its interplay with the reality principle.

Sketching the facts

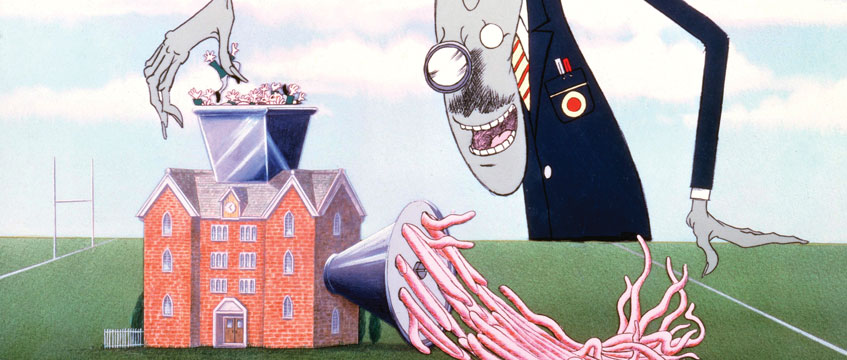

The cartoonist Gerald Scarfe was demised a long lease of 10 Cheyne Walk, London SW3 by the Earl of Cadogan in 1971. The lease was demised for a term of 49 years. On 13 May 2019, Scarfe gave notice to Cadogan Holdings Ltd, his then landlord, of his intention to acquire the freehold.

In August 2019, Fleur Alberti purchased from Scarfe the remaining unexpired term of the lease and the benefit of the enfranchisement claim. Cadogan and Alberti were unable to agree a price for the freehold owing to their differing interpretations of section 9(1A)(d).

Section 9(1A)(d) was engaged because during Scarfe’s occupation of number 10 he had lawfully converted it from a building consisting of multiple flats into a single dwellinghouse. At the material time the works were carried out, planning permission was not required as the works did not amount to a material change of use. In 2014, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea changed its planning policy. Planning permission would now be refused to convert a building containing multiple flats into a single dwellinghouse.

Drawing a line

Alberti argued that, in valuing Cadogan’s freehold interest, one would have to assume that Scarfe had not carried out the works. Accordingly, the use of the building as a single dwellinghouse on or after the valuation date would require planning permission, which would now be refused. On this basis, Alberti argued that the value of the freehold was £2.6m because the building would only have been of interest to buyers seeking a profit from the refurbishment of the flats.

Cadogan argued that section 9(1A)(d) was only concerned with the physical condition of the building. The provision did not require or permit any counter-factual assumption to be made about the use which could lawfully be made of it. Accordingly, it was lawful on the valuation date to use the building as a single dwellinghouse. Cadogan valued the freehold, subject only to the unexpired term of the lease, at £11m.

Playing with reality

The Upper Tribunal observed that an interplay existed between the “reality principle” and the direction given in section 9(1A)(d). In Harbinger Capital Partners v Caldwell [2013] EWCA Civ 492 it was determined that the reality principle provides that “where an amount is to be ascertained by postulating a hypothetical transaction, things are to be taken as they are in reality on the valuation date, except to the extent that the instrument postulating the hypothetical transaction requires a departure from reality”.

Relying on Shalson v Keepers and Governors of the Free Grammar School of John Lyon [2003] UKHL 32, the UT agreed with Alberti’s interpretation. The UT found that, in identifying the extent by which the improvement works had increased the value of number 10, a comparison had to be made between its value as it stood and what its value would have been if the improvements had not been made. A prospective purchaser buying the house in its unimproved state (namely, flats) would be advised that planning permission to convert it into a single dwelling would be refused.

The final picture

The Court of Appeal upheld the UT’s analysis. It found that both Shalson and Fattal v Keepers and Governors of the Free Grammar School of John Lyon [2003] EWCA Civ 1530 provided authoritative guidance on how section 9(1A)(d) should be interpreted. Importance was placed on the ordinary meaning of the language used in section 9(1A)(d). It required a counter-factual assumption to be made that the improvement works had not been carried out. Accordingly, at the valuation date the building would have comprised only of unconverted flats for which planning permission would not be obtained.

The purpose of the assumption was to ensure that the landlord did not get a higher price for the freehold than he would have done if the tenant had not undertaken the improvements. The UT’s interpretation underscored the “causal relationship” between improvements and the increase in value.

In respect of the interplay with the reality principle, the Court of Appeal found that it did not result in a different construction. Effect had to be given to the inevitable consequences of the assumed counter-factual state of affairs. As Lord Asquith observed in East End Dwellings v Finsbury Borough Council [1951] EGD 45, if a statute “says that you must imagine a certain state of affairs; it does not say that having done so, you must cause or permit your imagination to boggle when it comes to the inevitable corollaries of that state of affairs”.

Elizabeth Dwomoh is a barrister at Lamb Chambers