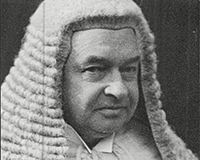

In 1923, the judge famously coined the phrase “not only must justice be done, it must also be seen to be done”. Stuart Pemble highlights its continued importance

Some cases establish important legal principles, others have practical consequences long after the legal ink has dried on the judgment. Ramsey J’s decision in Eurocom Ltd v Siemens plc [2014] EWHC 3710 (TCC) may do both. For an analysis of the case’s legal importance, see “One heck of a way to retire”, EG, 17 January 2015, p61. Following Hamblen J’s recent judgment in Cofely Ltd v Anthony Bingham and Knowles Ltd [2016] EWHC 240 (Comm), this note is concerned with the possible practical consequences.

The facts

In Eurocom, the court refused to enforce the award of the adjudicator – Tony Bingham – because Knowles (the firm of claims consultants which had successfully advised Eurocom in the adjudication) had secured his appointment as a result of fraudulent representations regarding the potential conflicts of interest of possible alternative adjudicators.

The judgment in Cofely arose out of an arbitration between Knowles (the referring party) and its former client, Cofely, over disputed professional fees. Knowles had successfully applied to the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (“CIArb”) for Mr Bingham to be appointed as arbitrator; an application that had been resisted by Cofely.

Following the publication of the Eurocom judgment, Cofely and its solicitors became concerned about the “nature and extent of the professional relationship between Knowles and Mr Bingham”. In February 2015, Cofely’s solicitors wrote to Knowles asking six questions about its relationship with Mr Bingham. The following month, having received a response to five of those questions, Cofely’s solicitors asked further questions of Knowles and also sent all of the correspondence to Mr Bingham.

Cofely’s solicitors also asked a number of questions directly of Mr Bingham regarding the number of adjudication and arbitral referrals he had acted on over the previous three years where Knowles had secured his appointment. They also asked for Knowles’s success rate before him and the percentage of his professional income effectively derived from Knowles over that period.

The nub of Cofely’s concerns can be gleaned from its solicitor’s final question to Mr Bingham: “What have you done during this arbitration to satisfy yourself that there is no information that you should disclose to Cofely which could reasonably be interpreted (on an objective basis) as undermining your apparent impartiality?”

Mr Bingham was initially reluctant to answer any question save to confirm the total number of appointments (both with and without Knowles) he had acted on over the previous three years. He was particularly concerned by the final question and asked Cofely’s solicitors: “What are you driving at please; or (forgive the vernacular) so what?”

Before the matter was heard by Hamblen J, there was nearly six months of correspondence on the issue and a hearing where (despite not being asked to do so by either party) Mr Bingham held that there was no bias. Eventually, with Mr Bingham having disclosed that a quarter of his income derived from appointments involving Knowles, Cofely applied for Mr Bingham to recuse himself. Mr Bingham did not reply so Cofley applied to court to remove Mr Bingham as arbitrator on grounds stated in section 24(1)(a) of the Arbitration Act 1996: “that circumstances exist that give justifiable doubts as to his impartiality”.

The judge’s findings

Hamblen J upheld Cofely’s application. In ordering that Mr Bingham should be removed as arbitrator if he did not resign, he highlighted a number of concerns:

- Mr Bingham’s relationship with Knowles was the key issue. The CIArb standard form for an arbitrator to complete when accepting an appointment requires the arbitrator to disclose “any involvement, however remote” with either party over five years. Despite the fact that 18% of Mr Bingham’s recent appointments as arbitrator and adjudicator and 25% of his income came from cases involving Knowles, he had failed to disclose this involvement.

- Although Knowles did not appoint an arbitrator or adjudicator directly, the evidence showed that it was able to influence appointments by proposing its chosen appointee and identifying required characteristics possessed by only a small number of people. In cases involving Mr Bingham, Knowles asked for the adjudicator or arbitrator to be both a quantity surveyor and barrister, joint qualifications which Mr Bingham shares with only a few other adjudicators and arbitrators.

- Eurocom showed that Knowles keeps a blacklist of people it does not want appointed. The fact that an adjudicator or arbitrator could be blacklisted by Knowles was “important for anyone whose appointments or income are dependent on Knowles-related cases to a material extent, as is the case for Mr Bingham”.

- The judge was also critical of the hearing where Mr Bingham unilaterally decided there was no bias. That finding was inappropriate (neither party had asked for it to be decided) and Mr Bingham’s conduct of the hearing “gave the impression that he was… pressurising Cofely into acknowledging that there was no issue to be explored”.

- Mr Bingham’s witness statement for the proceedings before Hamblen J showed that he did not recognise the relevance of his relationship with Knowles or why it should be disclosed.

Lesson to be learned

No-one was suggesting that Mr Bingham was biased. Rather, there was an appearance of bias which meant that justice was not being seen to be done. It was this which was fatal to Mr Bingham’s appointment (which he has since resigned). Anyone acting as an arbitrator should avoid a similar fate by keeping Viscount Hewart’s wise words in mind.

Stuart Pemble is a partner at Mills & Reeve LLP