As Magna Carta turns 800, Steven Gasztowicz QC makes a case for the Great Charter being as important to property law as to rights of personal liberty

As Magna Carta turns 800, Steven Gasztowicz QC makes a case for the Great Charter being as important to property law as to rights of personal liberty

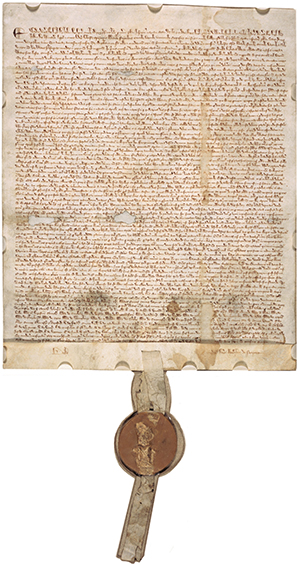

This year is the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta. Not of the signing of Magna Carta, as is often said. It was not signed. The King’s seal was simply attached to it, which was the way legal effect was given in 1215.

These are the sort of niceties that will appeal to property lawyers.

The frequent reference to this being the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta reflects the thinking of most people that signing is the way of giving something legal effect. It may or may not be. In our modern age, a unilateral promise to do something, even though signed, generally has no legal effect at all, unless made by deed. And such things as planning obligations under section 106 of the Town & Country Planning Act 1990 need to be made by deed in order to be effective.

Lawyers were as necessary in 1215 as much as now, to enable people to know what legal effect something does (or does not) have, and what formalities need to be complied with in order for it to be effective.

The almost short history of Magna Carta

Another thing that is not widely known about Magna Carta is that, within weeks of it being granted, it was in fact annulled by the Pope (who then held legal authority in such matters) at the request of King John. This demonstrates a further flaw in many people’s thinking that a document which is binding on execution will necessarily be binding thereafter and capable of being enforced. Property lawyers know otherwise. In our modern age, transactions can be set aside or the position restored, regardless of the legal document entered into – for example as a result of undue influence.

Magna Carta itself was annulled on the grounds it had been extorted by “violence and fear”, but was subsequently re-issued under Henry III, the following year (1216), after King John’s death. It was during the year after that (1217) that it first acquired its famous name (meaning the “Great Charter”).

Liberty and justice

Magna Carta is seen as a great symbol of our liberties, above all else enshrining the principle – accepted by the government (the King or those ruling for him), and binding upon them – that there shall be no imprisonment without trial.

Of course, lawyers are needed to say what “trial” means. Many people who refer to Magna Carta think this means trial by jury. Indeed, the wording at first blush suggests that – Clause 39 says: “No free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against him or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.”

However, this does not say how his peers shall judge him. In 1215, the usual way of a man’s peers judging guilt or innocence was by battle or by ordeal. If you were dunked and floated you were guilty; if you sank you were innocent, and so on. Interpretation, and what the judges declared appropriate, remained all.

Even aside from this, the caveat on the end of Clause 39 will at once be noted by property or contract lawyers. This is no guarantee of jury trial – or of trial at all. What is required is judgment “by the law of the land”, whatever that is from time to time laid down to be.

The same applies in relation to Clause 40 – “to no-one will we sell, to no-one deny or delay justice”. The first part seems clear enough – but by what standard is justice to be regarded as delayed (or not)? There are no absolutes, and these standards are of course set by the society that exists from time to time; in reality by the judges, or sometimes by the intervention of the parliament of the day, either directly or via rules committees. Modern day standards of “delay” will not be the same as those of 1215 (or even 1815), but the principle is as important in relation to property matters as in any other field.

The rule of (property branch) law

The importance of Magna Carta as a symbol of liberty is very powerful – and rightly so. Once entrenched, it established the rule of law. Even the King and his government were subject to the rule of law and could not proceed in arbitrary fashion, but had to abide by fundamental rules – even if they could, by process of law (the nature of which has changed over the centuries), fashion the detail of them.

But did Magna Carta have anything specific to say about property law? Wasn’t it all about notions of the liberty of the individual and justice under law?

Magna Carta in fact had a lot to say about rights of property.

It came into existence as much because of a demand for such rights as for the liberty of the subject. Many of the 25 rebel barons who took London from King John, and then negotiated the Magna Carta with him at Runnymede by way of settlement, were fuelled by injustices they had suffered in relation to succession and property matters.

One of the barons, William de Forz, for example, had claimed the English estates of the Aumale family through his mother’s line. King John refused to grant him his inheritance unless he married a lady nominated by the King. Her brother was another baron, Richard de Montfitchet, whose family had had custody of royal forests in Essex that were forfeited by his grandfather under Henry II.

Property matters were at the heart of the injustices which the barons wanted to put right and prevent for the future.

The property clauses

It is not surprising therefore that Magna Carta contained a number of property-specific clauses. The following are just some examples.

- Clause 2 provided for the heir of earls, barons or knights to receive their inheritance on payment of specified maximum sums, derived from what had traditionally been paid in the past on inheritance.

- Clause 3 provided that if the person inheriting was under age and in wardship, he was to receive his inheritance when he came of age without any payment being made.

- Clause 4 provided that the guardian of a minor who inherited could not take more than reasonable revenues, and must not destroy or lay waste to the land in his charge (giving rise to modern day trust notions). Interestingly, if he did so, the lands were to be taken out of his charge and entrusted to two prudent men who would be liable to do so (like court appointed trustees of today).

- Clause 5 provided that these guardians (or trustees) must also maintain the houses, parks, mills, ponds, and other appurtenances to the land from its revenues.

- Clause 7 dealt with widow’s rights, including the right to stay in the family home for 40 days after her husband’s death, during which period her “marriage portion” and inheritance was to be assigned to her (giving rise to modern day rights of occupation and widow’s inheritance rights).

- Clause 9 prevented distraint if the debtor was willing to pay (as now), and prevented land from being seized in payment of debts if chattels were available to satisfy it.

- Clause 23 provided that no-one should be compelled to use their land to build bridges over rivers, except those obliged to do so by existing custom and law.

- Clause 27 provided that if a man died intestate, his debts should be paid out of his estate, following which his possessions were to be distributed among his nearest relations (the foundation of modern intestacy law).

- Clause 31 provided that the King was not to take timber from private land (for building castles and the like) without payment.

- Clause 33 provided that all fish-weirs were to be removed.

- Clause 47 provided for land recently afforested by the King to be deforested and for enclosures to riverbanks to be removed.

These provisions were of sufficient importance to be repeated almost entirely in the 1216 re-issue, though other clauses were dropped.

These sort of measures were as important to Magna Carta, in establishing the rule of law, as those relating to trial. They laid down ground rules in relation to rights of property important to the time, and from which many of our laws have subsequently grown. More than that, such property rules for the first time established that even the King and his government had no right to arbitrarily interfere with people’s rights, but had to abide by rules laid down by law.

It is another of the myths surrounding Magna Carta that it had nothing to do with property matters. They were fundamental to how it established rights of justice, and the rule of law.

Steven Gasztowicz QC is a barrister at Cornerstone Barristers