There are four main ways to finance real estate development: equity, debt, forward funding and forward sales.

There are four main ways to finance real estate development: equity, debt, forward funding and forward sales.

Equity

The easiest way to fund a development is to use cash, structured as equity or as a loan from the shareholders. The property is likely to be held in a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that has been set up for the project, and any new money coming from the developer will have to be injected as share capital or as a loan.

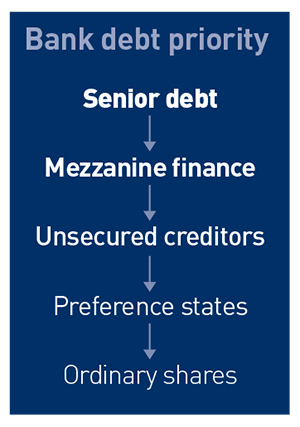

Because there is a tax deduction for interest, but not for returns on share capital, debt is attractive. Money from the shareholders of the SPV is likely to come in as a mixture of small amounts of equity and larger amounts of debt. Shareholder debt is often structured as a loan note or preference shares, which are hybrid shares that pay interest. If there is bank debt as well as shareholder debt, then shareholder debt will be subordinated (see Bank debt priority box below).

Debt

Debt can be called senior debt, mezzanine debt, junior debt, stretch senior, bridging finance and other terms, but in essence the bank lends money secured by a charge against the asset. The effect of using debt (referred to as “gearing”) is that the developer increases its return on successful transactions, but risks losing proportionately more equity on unsuccessful transactions. Using debt to help fund a project increases the size of project that

a developer can undertake given the amount of equity

that it has.

Mezzanine finance is often coupled with a senior loan. For example, on a development project, a senior lender might provide 60% of the development cost, with the mezzanine lender providing the next 20%. On these numbers, the senior loan is well secured and will charge a relatively low margin (perhaps 3% above the cost of funding). The mezzanine slice, however, has second ranking priority. This means that if, on eventual sale, there is a shortfall, the senior lender is paid in full before the mezzanine lender gets anything. The mezzanine lender is therefore more vulnerable and its margin will be higher, perhaps 15%.

Both loans will typically be secured against the property and there will be an inter-creditor agreement regulating the arrangements between the two lenders. In some regards, the mezzanine loan can be treated as quasi-equity. Although it is secured, it has the same sort of risk profile that new equity would have and has a much more equity-style return. The return might also include a profit share.

A few years ago, debt finance for development projects was very hard to obtain, but today, for good residential schemes and prelet commercial developments, debt is readily available up to levels of about 75% of the cost. High levels of debt might be available, at a cost, even for speculative or semi-speculative commercial schemes.

Forward funding is a completely different type of financing technique. Institutions and other investors sometimes struggle to find good investments, and one way to achieve a higher return is not to buy a standing investment but to buy a development that has not yet been built, but has been prelet. The fund buys the property, pays for the development and then, assuming all has gone well, pays a further, profit-related payment to the developer at completion.

Forward funding

Forward funding

So it secures a finished investment at a better yield than if the development had been built already, but takes on the additional risk of the construction process. From the developer’s point of view, it receives some cash immediately, secure funding for the development and, hopefully, a further payment at the end.

As the developer will be selling the undeveloped land to the fund, but also agreeing to carry out building works on the land sold, the fund will need to consider the correct treatment of the transaction for stamp duty land tax (SDLT) purposes. Sometimes the value of the building works will be included in the consideration that is chargeable to SDLT – for example, when the land is sold with the building works partly completed, SDLT will be charged on the land based on the condition it is in at the date it is sold (including the value of works done to that date).

If the land is sold before the building works have commenced, the developer and the fund are likely to enter into a separate agreement whereby the developer agrees to build the property and the fund agrees to pay the construction costs plus a profit-related payment to the developer at the end of the development. If the obligations on the developer to construct the development are so interlocked with the agreement for the sale of the land (for example, where the agreements are conditional because the fund can return the land to the developer if the development is not completed), then SDLT will be charged on the land as if the works had been completed (on the consideration given for both the land and the development works).

But if the sale agreement and the construction obligations are independent of each other, no SDLT will be charged on the consideration given for the development work. There must be a just and reasonable apportionment of the total consideration given by the fund for the different elements of the transaction so the fund pays the correct amount of SDLT on the consideration attributable to the sale of the land.

In terms of the mechanics of the funding, the fund agrees to pay a maximum amount for the completed development. At the start of the project, the fund opens a development account and various costs (including the land acquisition, construction and any other costs incurred during the development) will be charged to this account. A notional rate of interest accrues on this account (typically more expensive than senior bank debt but less than mezzanine finance). Once the development is complete and the lease can be granted to the tenant, there will be a balancing payment to the developer equivalent to the maximum amount that the fund has agreed to commit, less the current balance on the development account.

Because the land is transferred on day one, this approach is not generally compatible with bank finance (although, in principle, the fund could borrow with the property as security), so is more typically used by institutions that pay cash.

Forward sales

This is where a developer enters into an agreement with a fund or other institution to buy the completed development for a fixed price after completion of the project.

The advantages for the fund are: (i) it usually only has to pay any money once the scheme is successfully built and let, and (ii) it takes no construction risk. The disadvantages for the fund are: (i) it probably has to pay more for the privilege and it is likely to have a higher SDLT cost than if it had bought undeveloped land; and (ii) the fund has committed part of its capital but will receive no return until the project is finished, a year or more away.

This technique is much less common than it once was, but the main attraction from the developer’s perspective is that it makes funding the ongoing development up to completion much cheaper. Because the fund is not paying for the construction, the developer will have to find the money elsewhere, but due to the guaranteed exit at a fixed price, a traditional lender will be comfortable lending more and at a cheaper rate of interest than if the property would have to be sold in the market at completion. Typically, the bank will lend a proportion of the end price subject to a contingency for the risk of construction going wrong rather than lending a percentage of the construction cost, which will be rather lower than the exit price. So, from the developer’s point of view, it does not solve the funding problem during construction but makes it easier to get bank debt, and offers a higher exit price than a forward funder would pay.

Why this matters

Having settled on the right funding technique for their business model and circumstances, investors and developers will need to consider a number of issues with their advisers.

• Lenders will take security over the property itself but may also require security over construction documents and collateral warranties in their favour to give themselves rights against the construction team. The funder may also want the right to approve the form of the building contract, professional appointments and warranties.

• In all funding arrangements, address these issues: treatment of cost overruns; default by the contractor or a member of the professional team; default by the tenant that is due to take the lease; step-in rights for the funder under the construction agreements if the developer does not perform.

• Consider responsibility for costs such as: environmental clean-up costs; neutralising third-party interests, such as rights of way, rights of light or restrictive covenants; CIL/section 106 payments and affordable housing issues; any overage costs on the purchase of the land or the implementation of planning consents.

• Consider the tax treatment of: the purchase of the land, the development and any subsequent disposal (SDLT, VAT, capital allowances, Construction Industry Scheme obligations, capital gains tax/income tax/corporation tax); payments made to the lender – are interest payments deductible against the borrower’s income/corporation tax liability and does the borrower need to withhold tax on interest payments to the lender?; rental income – will there be a tax deduction from rental income under the Non-Resident Landlords’ Scheme?

• Does the development agreement constitute a “construction contract” under the Construction Act 1996? If so, this will affect the interpretation and operation of the agreement.

• Securing the letting to the tenant is usually integral to the completed development’s value, so funders should ensure the conditions in the agreement for lease for the grant of the lease (and calculation of the rent) are fully reflected in the provisions for the final payment to, and release of, the developer under the development/funding agreement.

• Ideally, the agreement for lease will make it clear that the developer’s construction obligations are not treated as landlord covenants that will pass to the buyer on the sale of the property.

Anthony Judge is a partner and head of the real estate team at Travers Smith LLP