Karen Baxter and Lucy Hendley set out the steps to take if your business is accused of being a toxic workplace.

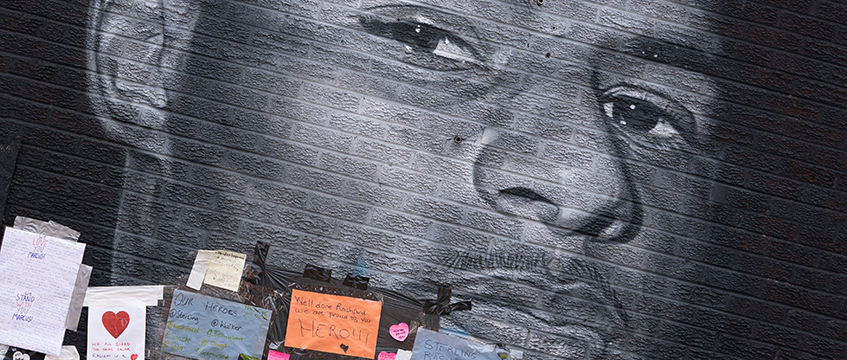

The despicable racist abuse of Black members of the England men’s football squad on social media following the Euros final on 11 July led to calls by some to identify the perpetrators’ employers as a way of holding them accountable. This was seen most prominently in the real estate sector, where the employee of a major real estate agency was identified on social media as the alleged author of a racist tweet (he argues that his account was hacked and the tweet posted without his consent).

Since then, further stories have emerged of experiences of racism in the real estate sector. This prompts the question: is real estate the next industry to be the focus of allegations of widespread discrimination or toxicity in the workplace? And is your organisation ready to deal with any allegations properly?

Dealing with allegations

When an allegation is made (whether publicly or not), the actions within the first 12 hours are critical. This is impossible to achieve unless you have a group of people in the business who are empowered to act, understand the risks, and know what is expected of them. It is important to build this into your risk management plans.

Often, serious allegations can cause “decision paralysis” because a crisis scenario has never been worked through in advance. It leaves people scrabbling to gather their thoughts and create an action plan. Knowing who makes decisions and which external advisers to call upon is key. It is also important to keep those who are accused of wrongdoing away from the process, even if they were the very people who would normally handle it.

Any investigation needs to be seen as authoritative and truly impartial. If the findings are to be accepted, complainants need to have confidence in the impartiality of the investigator and their ability to investigate without fear or favour.

Choosing the right investigator is important; the person needs to have appropriate experience and sufficient time to dedicate to the task. They need to be appropriately senior, particularly where fingers are pointed at those in management positions. Employers need to think carefully about whether they have the right person in-house, or whether they need to look externally. Thought should be given to the wellbeing of the people accused of wrongdoing and of the accuser. The process will be stressful and challenging for them all.

One of the first things for an investigator to do is to try to get more information. Allegations might involve anything including bullying, discrimination, intimidation, under appreciation, lack of trust, cover-ups, or even all of the above. The investigator will need to speak to those raising the complaints and potentially a wider group of employees to find out more from them, asking open questions about the workplace that they have experienced.

Although it can be widespread, “toxicity” often exists in pockets, being caused by people holding power and wielding it inappropriately. There may be some preliminary interviews needed before an investigator is really able to understand the scale of the job involved. The employer will need to decide who can control the scope of the investigation: is it up to them or does the investigator have free rein? It is important to be clear about these issues from the start.

When allegations are made, employers will understandably have a desire to fix things quickly. But there is no quick-fix in a situation like this. If an employer rushes a report out too soon, they risk being seen as not taking the allegations seriously. Conversely, the same can be said if an investigation moves too slowly and nothing seems to be being done – there is a risk of not prioritising the problem. There is a need to balance speed and thoroughness, and it is important to find the sweet spot.

Toxicity is more than just the actions of some wrongdoers. It is pervasive. A toxic culture exists where there is the infrastructure to support it, so an investigation into toxicity needs to dig deep. As well as investigating particular incidents, it must look at the actions and values that are supporting a toxic culture, and make recommendations for how they can be dealt with.

Once an investigation is complete, the report is likely to make for very difficult reading. If the investigation has been done properly, it may have exposed incidents and behaviours that will have gone previously unknown. Equally, the findings may be critical about people who were once trusted individuals.

The findings must be addressed. The investigation may lead to spin-off disciplinary proceedings, potentially involving very senior figures in the business. The company must be willing to take the findings on board and act on them. However, dealing with the bad behaviour of individuals is, in many ways, the easier problem to tackle. The more difficult problem is bringing about a culture change. Shifting a workplace culture from one of fear and bullying to one of support and trust takes time, effort and leadership. Trust is easily lost and difficult to rebuild.

Achieving a lasting change

A crucial element of creating the support and trust in your workplace environment is making sure everyone understands the organisational position on workplace behaviour. Training plays a vital role in ensuring staff not only understand the issues around diversity and harassment but enables them to clearly see what their role is in creating the workplace culture being strived for.

Training has long been recognised as a step that must be taken by a business if it is ever in the position of having to defend a discrimination claim. Employers who have been in this position will know of the significant consideration given to the question of whether staff were trained in the provisions of the Equality Act 2010 and how long ago that training was. The “reasonable steps” defence to a harassment claim requires an employer to be able to demonstrate that it took all reasonable steps to prevent the harassment or discrimination from taking place. Key to this is ensuring staff are familiar with the employer’s diversity and anti-harassment policies and understand the types of behaviour that can amount to discrimination. Training is a significant step to achieving this but effective training is not a “tick-box” or cursory one-off session. Rather, it should be embedded into business culture, informing and educating employees at every level, on a regular basis. It is this that will help organisations achieve that lasting change.

Training on discrimination does more than provide protection in the event of a discrimination claim. Effective, proactive training will give staff an insight into the experiences of people who have different characteristics and help to foster an environment where no one feels excluded or discriminated against because of their differences. An inclusive workplace is far more likely to lead to happy, productive staff, and significantly reduces the risk of losing talented people who aren’t in the majority. Facilitating sessions for leaders and managers on how to role-model the right behaviours and “speak up” sessions for staff builds confidence and trust that they will be heard. Not only can policies be highlighted, it provides an opportunity to remind staff where they can go to gain support and what they can expect from the organisation.

So often discriminatory behaviour is not deliberate or intended and simply dismissed as “harmless banter”. Responses such as, “I didn’t mean to offend, I was only joking…” are common, but it is important to remember that intention is largely irrelevant. The effects are the same for the person receiving the treatment and it is their view that would be the focus if a discrimination claim was brought in the tribunal. Training can be a significant tool to help people consider things from another person’s perspective and remind them of the characteristics that we cannot see but which can nonetheless drive how we react to a certain comment or joke.

There has been a great deal of focus on diversity and inclusion in recent years and for good reason. It is not just a “nice to have” – the economic benefits of a more diverse environment are obvious; with greater diversity comes greater innovation, something no business can afford to ignore. By investing in people and taking the time and energy to create the best, most inclusive environment possible, not only are businesses more likely to avoid the fallout of a discrimination allegation, they can reap the benefits of a body of staff who feel valued and supported by leaders who believe in, and role-model, the inclusive behaviours we all have come to expect.

Karen Baxter is a partner and head of the investigations and regulatory group and Lucy Hendley is a managing legal trainer at law firm Lewis Silkin