Key principles on a 1954 Act renewal following O’May

• The court’s starting point is the terms of the existing tenancy but it has discretion to change those terms or impose new terms

• The onus is on the party seeking change to persuade the court to that effect

• There is no onus on the court to make changes on the basis of what a landlord might argue is the prevailing market practice, even where tenants might typically accept a change

• However, the 1954 Act does not require a court to “petrify” the lease with terms that are otherwise outdated or unsuitable

• To the extent that any change is imposed on a party against its will, there must be “good reason” for the change on the basis of “essential fairness”, considering the “circumstances of the case”

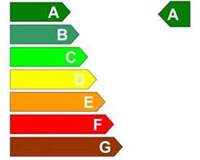

“Green lease” provisions, designed to improve the environmental sustainability of buildings, are yet to be included automatically in commercial leases. The issue is likely to be highlighted afresh with the introduction of minimum energy efficiency standards (“MEES”), which present an interesting question in the context of renewals under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (the “1954 Act”). How will the two statutory provisions interact?

“Green lease” provisions, designed to improve the environmental sustainability of buildings, are yet to be included automatically in commercial leases. The issue is likely to be highlighted afresh with the introduction of minimum energy efficiency standards (“MEES”), which present an interesting question in the context of renewals under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (the “1954 Act”). How will the two statutory provisions interact?

1954 Act renewal

If an existing lease has been “contracted-out” of the 1954 Act, typically the nature and extent of updating on renewal will reflect the negotiating positions of landlord and tenant. However, where the tenant occupies under a 1954 Act “protected” lease, the tenant’s right to a new tenancy influences that position.

In the event of disagreement, the court can be asked to determine the terms of the renewal lease and, in negotiation, the parties will have regard to the likely order a court would make. A party that adopts a stance widely at odds with the court’s likely position will risk the time and costs associated with court proceedings.

Section 35 of the 1954 Act governs the court’s power to make an order as to the terms of a new tenancy (except for duration and rent, which are dealt with by sections 33 and 34). It requires that the court “shall have regard to the terms of the current tenancy and to all relevant circumstances”. The leading judicial authority on interpretation of this section is O’May and others (Practising as Ince & Co) v City of London Real Property Co Ltd [1982] 1 EGLR 76 (see “Key principles on a 1954 Act renewal” box).

The case presents a potential hurdle where a landlord is looking to “green” a protected lease on renewal. An attempt to impose provisions that a sitting tenant might consider more onerous may find little favour with the court, particularly if they have the potential to disrupt occupation or impose additional expenditure on the tenant.

The impact of MEES

MEES are set to bite in 2018 (on lease grant, including renewal) and in 2023 (for all existing leases). For properties at risk, MEES need to be considered now on renewals, especially if the term will span the 2023 deadline. To avoid future fines (or the need to rely on an exemption), a landlord may look to bring a property up to a “safe” energy performance certificate (“EPC”) rating now and/or ensure that any lease granted protects its MEES position. However, until there is direct authority on the point, it remains unclear how a court will approach the landlord’s need to consider MEES. Can a landlord justify MEES-related updating to address the risks ahead? Will a court now consider this to be fair and reasonable?

It is unlikely that an existing lease will require a tenant to carry out necessary improvement work, reserve sufficient rights for the landlord to do the work itself, or – if a tenant allows its landlord to carry out improvements – permit the landlord to recover the cost. Even if the landlord is willing to undertake the work at its own cost, a tenant may suggest that enhanced rights of entry could disrupt the operation of its business.

How then can a landlord comply? A landlord may persuade its tenant that it will benefit from improvements with lower operational costs. In addition, a tenant might wish to underlet (when MEES would also apply), so it may be in the tenant’s interest that the work is carried out. On the basis of O’May, a landlord may struggle to persuade a court to include terms against the tenant’s wishes, although if a property is already at a “safe” EPC rating it is likely that the court would be receptive to restrictions on a tenant from acting in a way which jeopardises that rating (eg alterations).

The “consent” exemption

A landlord will be able to claim an exemption from reaching the MEES minimum standard for five years where, “despite reasonable efforts”, a tenant refuses consent to energy efficiency improvements. On a 1954 Act renewal, it will have a six-month window in which to comply (should negotiations fail adequately to address MEES). There is an administrative burden on the landlord in claiming and renewing this exemption.

The government has suggested that a landlord will have to “demonstrate reasonable endeavours in seeking consent”, indicating a determination to ensure that the exemption is not used “to deliberately avoid taking action”. Non-statutory guidance is expected to expand on what is required of a landlord in order to rely on this exemption.

Drafting for MEES

MEES-related drafting will increasingly become a feature of commercial leases and may be particularly controversial in the context of 1954 Act renewals. As MEES-related improvement work may benefit both landlord and tenant, it is possible that there will be an element of cooperation on terms. Nonetheless, it remains to be seen how 1954 Act protected tenants will react and how, should it be required, the courts might respond.

For more on MEES, see “A guide through the MEES minefield” (EG, 25 April 2015, p76) and “Putting MEES first” (EG, 8 August 2015, p48)

Ed Glass is a solicitor at Bristows LLP