Barbara Webb and Mark Gauguier look at the additional complexities involved with a charge of part of a property, and various possible ways lenders can protect all required rights over the retained land

What is the difference between a charge of the whole of a property and a charge of part? Charging part may be preferable, for example, where a developer needs the activities on part of its land to be outside the lender’s control, or where the lender needs security over the most valuable part of the land. Either way, the value of a charge is dependent on the ability of the lender to enforce its security if the borrower defaults.

Additional thought is required for a charge of part, particularly in relation to easements. On a disposal by the lender after a borrower default, the charged land will need the benefit of all necessary rights over adjoining land (access, passage of services, etc) so it can function as a self-contained property. However, unlike a transfer of part, rights granted in a charge of part might not be effective.

The problem

An easement requires both dominant and servient land, each in separate ownership. An easement is extinguished when both properties come into common ownership (“unity of seisin”). As such, easements cannot be granted by a borrower in a charge of part because, at the point that the charge is created, the borrower owns both the dominant (charged) land and the servient (retained) land. This is a significant hurdle for a lender taking security.

Getting around the problem

There are several potential ways of trying to ensure that charged land has all necessary rights over the retained land, some of which are set out below. These can be successful in the right circumstances, but there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Charge it all?

The simplest solution is for all of the property to be charged, with the result that no easements are required until or unless the borrower defaults and the property is sold in parts (at which point the rights can be created).

In a residential context this may be the preferred approach. The CML Handbook states that if the charged land needs rights of access or for the passage of services over the borrower’s retained land, then the retained land must also be charged to the lender. While this may be appealing from the lender’s perspective, in many circumstances (particularly with commercial sites) this may not be appropriate.

Section 62?

Alternatively, the borrower can grant the rights in the charge and the lender can rely on section 62 of the Law of Property Act 1925 to crystallise the rights into full easements on the sale of the charged land. However, there are limitations to the operation of section 62, particularly where there has been no previous diversity of occupation. For the right to crystallise into an easement it must have been enjoyed by the charged land only (rather than by the whole) and must be continuous and apparent (Wood and another v Waddington [2014] EWHC 1358 (Ch); [2014] 2 EGLR 151).

In our example below, where Buildings A, B and C all use the same right of way, there would certainly be doubt over the effectiveness of section 62. While the Land Registry appears (anecdotally) to support the creation of quasi-easements which crystallise through section 62, the uncertainty surrounding this approach means it is unlikely to be satisfactory to lenders.

A practical example

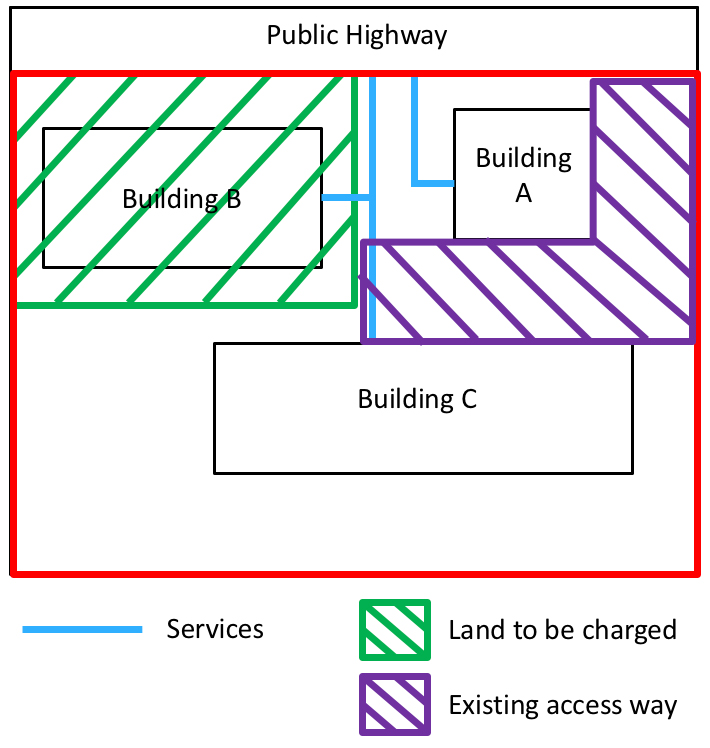

• X owns the property edged yellow (“the property”).

• X wishes to borrow and offers to charge the part shaded green (“the green land”) as security.

• Buildings A, B and C all use the access way and the unadopted services within the property.

• The lender needs to ensure that, if X defaults, it can sell the green land as a self-contained property with all necessary rights.

• X cannot grant in the charge the necessary rights for the benefit of the green land over the remaining land (“the retained land”), because at that point X owns the whole of the property.

Split it?

If the borrower is a company (and subject to any tax considerations) a solution might be found before the lender is involved, or at least before the charge is granted. The land can be split into separate ownership, using group companies or a new special purpose vehicle, with all necessary rights and reservations granted at that stage so that the lender takes a charge of the whole.

Using our example, the green land would be transferred and then registered in a separate title and the transfer would include rights over the access way and to use and connect into the services. Depending on the nature of the site, this option can be time-consuming and involved, but it is effective. However, it may not be possible to do this if the property is owned by an individual or an organisation whose structure does not permit such a division.

Best of a bad bunch?

Assuming it is not practicable to split the land, the limitations of the existing law would leave most lenders with little alternative other than to place an obligation on X to join in any later disposition by the lender to grant all necessary easements over the retained land. To avoid disagreement in the future as to the rights required, careful thought must be given to those rights on the grant of the charge, and there should be a general “sweeper” provision to capture any further rights that may be identified.

However, this solution remains less than ideal as it is a contractual obligation and relies on the lender suing for breach of contract if X fails to perform. This approach also relies on X being able to join in the disposition that the lender wishes to effect. Where X is an individual the lender may take comfort that X is unlikely to change (save in the case of death). However, if X is a company which no longer exists when the lender is making the disposal, or is subject to an insolvency regime, the borrower may need to be “restored” to the Companies House register or the lender may have to look to its administrators or liquidators before securing the required rights.

Changing the system

The Law Commission’s report Making Land Work: Easements, Covenants and Profits à Prendre recommends that the unity of seisin rule should be abolished so land owners may create easements that benefit and burden identified parts of their own land, while they continue to own the whole. This would, for example, allow a developer to create individual plots before they are sold, simplifying the procedure not only for mortgaging the plot but also for land registration.

Looking back to our example, this would allow X to create all the rights the green land requires ahead of the charge to the lender. If the lender’s power of sale was later exercised, the green land would already have the rights and the lender need not rely on a contractual obligation. This approach would still require careful consideration of the rights that the charged land might require and lenders may still need a sweeper provision.

The Law Commission’s proposals have been well received: the briefing notes to the Queen’s Speech on 18 May referred to a new Law of Property Bill which would respond to their report. Until the proposals become law, however, lenders will have to rely on the existing options, warts and all – with a healthy appreciation of the risks that each one entails.

Barbara Webb is an associate and Mark Gauguier is a partner at Farrer & Co LLP