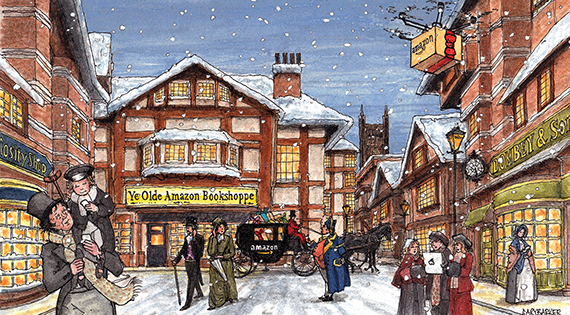

From this November, residents of Seattle have been able to take part in an unexpected retail experiment. Twenty years after it first started selling books online, Amazon has opened its first physical bookstore in the city. Called Amazon Books, the shop, in Seattle’s University Village, stocks around 6,000 titles based on reviews and sales data from Amazon.com.

Why would the world’s biggest online bookseller take what looks like a technological step backwards? Because Amazon, like many online retailers, has a discovery problem. Put simply, Amazon is bad at helping consumers discover new products. It supplies existing needs brilliantly, but does a poor job of exciting new ones.

According to Nielsen’s 2015 Books and the Consumer survey, two-thirds of online book purchases are planned in advance, while only a third are impulse buys. In a bookshop the reverse is true: 41% of bookstore purchases are planned, whereas the majority are impulse buys. In the linear environment of e-commerce, people go in, get what they want, and leave. In a bookshop, they browse, pick things up and put them down, and depart with a purchase inspired by serendipity and association. Amazon’s “People who bought this also bought that” simply can’t compete.

This problem has always existed, but the sudden switch to mobile has made it much more evident. On the smaller screen – which since 2014 is where the majority of digital media is consumed – people are less likely to browse than they were before. Even Google, the world’s most efficient search engine, is feeling the pinch, with fewer searches coming on mobile as people spend more and more time in apps. In any case, Google is another internet giant that has a problem when it comes to discovery. After all, how do you search for something you don’t even know about?

New players are challenging the established order. Facebook wants to “own” discovery by placing it at the centre of its Facebook Messenger platform. In this vision of the future, you would see a T-shirt your friend liked, then send a picture of it to the retailer saying, “Get me one of these.” Amazon is then merely the unseen supplier.

Seeing this threat, Amazon earlier this year introduced Amazon Dash, a connected button that can be stuck to a fridge or bathroom cabinet. When you run out of toothpaste, simply tap the Dash and it will automatically order a new box, to be delivered that same day, perhaps even by drone.

Another similar solution is Amazon Echo, a digital “personal assistant” for the kitchen that takes voice commands and answers questions on various topics – as well as adding items to shopping lists, supplied of course by Amazon Fresh, Amazon’s new one-hour grocery delivery subsidiary, now being tested in central London.

But sometimes old technologies can’t be beaten. Until the day comes when we can all shop in virtual reality, old-fashioned retail curation is still the best way to find out about new products. Mere buying can be done online. To shop, we need the store.

Rowland Manthorpe is associate editor at Wired