When QIA and Brookfield first made an approach to Canary Wharf owner Songbird, its £2.2bn bid was laughed off as “significantly undervaluing” the firm.

When QIA and Brookfield first made an approach to Canary Wharf owner Songbird, its £2.2bn bid was laughed off as “significantly undervaluing” the firm.

Last week the pair made a final bid of £2.6bn – still below the valuation published by Songbird in defence of the bid. But this time it was not immediately dismissed.

Why? The answer is hidden in the complex world of valuation.

NAV is the widely accepted measure of a property company’s fair value. And yet Songbird’s board stopped short of immediately shutting the door on the bidders’ sub-NAV offer.

Unlike its speedy and unequivocal response to the consortium’s initial 295p per share offer, the Songbird board did not reject the revised bid outright, even as it stated the offer was still “too low”.

So why is the sub-NAV bid being given any credence?

In their revised offer statement, QIA and Brookfield emphasised their bid of £2.6bn represents a 15.1% premium to triple NAV, which they feel is a fairer measure.

Triple NAV is sometimes described as the “break-up” value of a company. Unlike NAV, which values a company as a going concern, triple NAV provides a spot figure which adjusts for hidden losses in illiquid assets and liabilities.

According to the European Public Real Estate Association definition, triple NAV reports “net asset value including fair value adjustments in respect of all material balance sheet items which are not reported at their fair value as part of the EPRA NAV”.

For Mike Prew, head of real estate at analyst Jefferies, the fact that Songbird’s revised valuation only took into account the “left-hand side of the balance sheet” – ie the assets and not the liabilities – is its “Achilles’ heel”.

This is because Songbird has £1.6bn of long-dated securitised debt, which costs it significantly more than the current market rate.

Songbird’s triple net asset value adjusts for this circa £547m impact on NAV.

And it also takes into account around £270m of deferred tax, which, given that Songbird is not a REIT, it would have to pay should the company’s new owners choose to liquidate its assets.

This is unlikely given the nature of the bidders, but nevertheless something which has a legitimate bearing on a company’s market value.

Triple NAV normally features prominently in Songbird results bulletins, but was conspicuous by its absence from the top of the valuation update it gave in defence of the first offer from QIA and Brookfield.

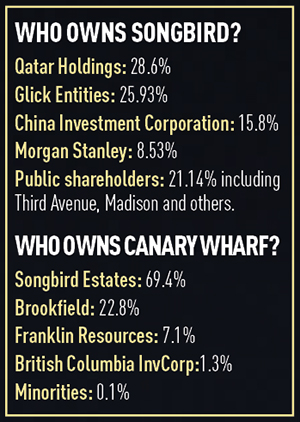

The bidders also emphasise that Songbird shares have consistently traded at a significant discount to NAV, in part thanks to its much-maligned corporate structure (see box). In the six months prior to the bid, Songbird shares traded at around 250p.

So far the bidders’ proposition has been compelling enough for the holders of around 32% of the Songbird free float – including Third Avenue, Madison and EMS – to agree to accept.

But QIA and Brookfield are still well short.

Even if they manage to win over all of Songbird’s free-float shareholders they will only control 49.5% of the company.

So the decision is entirely in the hands of Glick Entities, Morgan Stanley and China Investment Corporation.

Glick is widely considered the least conducive to a deal with the consortium, while Morgan Stanley is likely to be a trader, albeit at the right price.

This view is highlighted by the bidders’ strategy of making their second offer final – meaning if it is rejected it cannot make another approach for six months.

While some have questioned the tactic, the bidders considered Morgan Stanley unlikely to do a deal if it felt there was the potential of a higher bid to come.

For Chinese state fund CIC a sale would net an outstanding return, but it would find it hard to reinvest in a similar calibre property opportunity.

In reality, CIC remains something of an unknown quantity, particularly because it has not exercised its right to board representation. And it is the make-up of the board that could ultimately prove crucial.

Even if the bidders do manage to convince one of the major shareholders to back their bid, QIA and Brookfield will have another hurdle to navigate.

A legacy of the last hostile tussle for control of Canary Wharf is an article in the company’s constitution which states that should any major shareholder sell, the buyer of those shares is not necessarily entitled to take up their representation on the board.

Glick representatives occupy three board seats, so any decision by Morgan Stanley to sell, and thereby reduce the size of the Songbird board to eight, would effectively give Glick a blocking stake against the two-thirds vote required to collapse the company’s structure.

The articles allow for this to be changed, but doing so would require the support of QIA’s fellow board members.

How far its influence extends will now dictate potentially the biggest argument about property valuation in UK corporate history.

jack.sidders@estatesgazette.com