The seven recommendations in the British Property Federation’s build to rent manifesto could not have come at a more auspicious moment.

As the Conservatives reaffirm their commitment to home ownership across the UK, the burgeoning private rented sector looks to have been sidelined in favour of the old adage “a man’s home is his castle”.

For those that have watched the PRS steadily gather momentum both in London and around the UK in the past three years, headline-grabbing announcements around right to buy and starter homes may seem a disappointment.

But as the manifesto shows, the PRS is finally at a stage where it is playing its part in providing thousands of homes across the UK. The continuing crisis of supply means its

input cannot be ignored, whatever national policy may say.

However, what the recommendations also show is that a lack of guidance at the national level means there is still work to be done in approaching, educating and cajoling authorities into realising the benefits of building for rent – which needs the continued support of national government.

Less overt support

Those behind the manifesto remain upbeat about the support the PRS is receiving.

“I think the government is still very much in favour of build to rent, but has been less vocal about it,” says Duncan Salvesen, director at investor Dorrington.

“There has certainly been a significant amount of support from the housing minister, and I am certain that is still there and he sees the benefit. It is not receiving the headlines of build to sell, but I still think that government believes it is part of the solution.”

Ian Fletcher, director of policy at the BPF, agrees: “What they are not going to be doing at No 10 and the Treasury is banging the drum for renting, because they have to stay on message that this is a government for home ownership.

“But that won’t stop discussions with the department for Communities and Local Government on how to continue to support the PRS. The key selling point, that fundamental reason for having the Montague Review and encouraging the sector, remains as pertinent now as it was then: attracting new supply and new players into housing provision.”

Numbers that do not add up

That key selling point – increasing housing supply – is one such reason that there is little chance of the sector being forgotten.

Whether the government can provide 200,000 starter homes in the next five years – as it plans to do – is immaterial, compared with future rental demand.

There are now 5.4m private renting households in the UK, according to PwC, and it is the UK’s fastest-growing housing tenure. It estimates there will be 7.2m by 2025.

“For the government to achieve its [annual] 50,000 target of starter homes, that is 50,000 tenants leaving the PRS. There will be an impact. But given there are 1.3m moves a year in the rental market, 50,000 purchases will not upset the dynamics too much,” said Richard Donnell, research director at Hometrack.

Meanwhile, 250,000 homes are needed each year to meet housing demand, while just 112,000 were built in 2014. Realistically, according to Savills, private housebuilders will not supply more than 160,000 units a year.

Against this, the BPF estimates there to be £30bn in institutional capital available to invest in rental housing. Those institutions, according to Salvesen, “have the funds available, and are seeking to deliver quality homes with quality management”.

The government’s home-ownership plans are unlikely to derail that weight of capital. “We are still carrying on trying to acquire sites, we do not see the housebuilding industry being able to solve the problem, and there are still opportunities to provide housing in the top eight cities outside London,” says Andrew Pratt, residential consultant at investment manager Patrizia.

As more sites come online, the numbers for the PRS are also starting to stack up.

At the end of the summer, the Investment Property Forum released a viability report saying that a hypothetical 1,000-home scheme in London could be delivered 2.5-times faster if 70% was PRS.

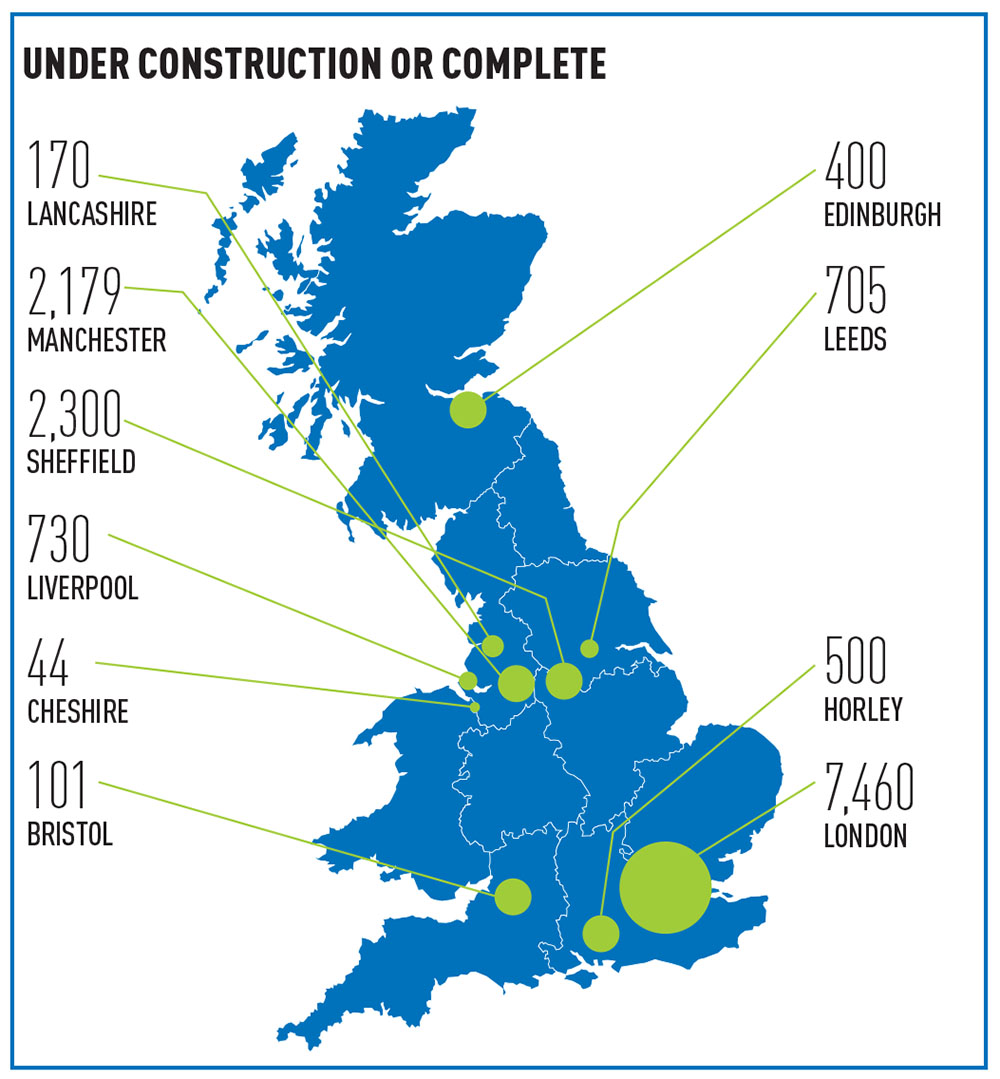

The BPF’s accompanying research with its manifesto shows almost 15,000 homes under construction or completed (see map). It estimates it has caught 90% of the market, but there are still thousands more either in planning or under offer.

In terms of national housebuilding it is a small start, but an increasingly important contribution to housebuilding totals.

According to Andrew Stanford, residential fund manager at LaSalle Investment Management and previously head of the PRS taskforce: “The purpose of the manifesto is to reinforce to national and local government that build to rent is no longer a theory, it’s a reality, and it can continue to grow if it receives support.”

The problem is that it does still need that national support. Numbers still do not stack up for buyers when competing against housebuilders. The IPF report says that PRS investors can expect an annual return of 7.5%, compared with 17.5% for housebuilders.

The PRS roadshow

In London, where rental demand is highest, the PRS has been written into policy.

“We were rather encouraged by the GLA support through its draft special planning policy guidance, which underlined affordable housing on build-to-rent schemes could have discounted market rents, alongside recognising the rental covenant,” says Stanford.

But support is rare outside London.

According to Fletcher: “The most important recommendation is about acknowledging what London has done planning-wise and rolling that out across the country. In London, the GLA and the mayor have been very active in using covenants and clawbacks, and saying the affordable offer on build to rent will be discounted market rent.

“The mayor’s support of planning policy, and the local authorities getting behind that, have meant schemes have got off the ground. It would be a significant step to roll that into planning guidance across the country.”

National support and guidelines are crucial as the same issues remain around PRS outside London – its value still needs to be demonstrated to councils. This is especially relevant in the disposals of public land, where, at least at first, PRS does not deliver as much cash as build for sale. But it does have other advantages.

“It’s not a case of less money, but the return profile is different,” says Fletcher. “If they enter into a joint venture with the developer, they will get a share of that income. And the local authority has kept some control of the family silver.”

It is also essential to explain the value of rental covenants, clawbacks and how PRS is affordable housing, compared with housebuilding.

According to Jason Hardman, senior director at CBRE Residential: “There are isolated examples of where there are supportive councils, but I don’t think it is widespread across the country, and that’s partly because we have not seen large-scale development for the best part of a decade for a lot of local authorities.

“When something new comes along, it’s very difficult at a local level to get to grips with it – because they have no direct experience of it.”

He adds: “The manifesto is all about this: trying to raise the profile of the build-to-rent sector, by helping councils take into account that the numbers do work in a different way.”

So, while the Conservatives’ starter homes initiative and right-to-buy schemes may be encouraging home ownership, the hard-won place of the PRS is not likely to be eroded – but there must be support from government.

“What investors and developers need to engage in substantial PRS investment is encouragement from the government, not necessarily in monetary terms, but in the removal of red tape,” says Andrew Taylor, head of UK residential investment at fund manager Internos Global Investors.

“Build to rent has enormous potential to deliver additional homes to the UK,” concludes Melanie Leech, chief executive of the BPF, “and government must not overlook this in blind pursuit of making us a nation of homeowners.”

Manifesto recommendations

Manifesto recommendations

1 Plan for build to rent

Capital is tied up for less time when building for sale: new homes are sold and the housebuilder derives a profit. When building for rent, investors tie up capital for 10, 20 or 30 years. There is no instant profit as investors are taking income, making the viability of build to rent more challenging.

National policy should oblige local authorities to measure demand for market rented housing and to plan for that demand, allocating land in local plans for build to rent.

2 Covenants, clawback and discounted market rent

In London, the GLA supports build to rent through supplementary planning guidance, which stresses that affordable housing on rental developments should be discounted market rent. This helps viability and allows investors to manage the affordable and market rented elements as one, while making the affordable units tenure blind. To ensure DMR is restricted to PRS developments, authorities should place a covenant on the development, retaining it as market-rented homes for a fixed period, with clawback provisions if the homes have to be sold. This approach in London should be adopted as national planning policy.

3 Promote better use of public land

Rental providers have difficulties competing with build-for-sale for private land, which makes them more reliant on access to public land, most of which is held by local authorities.

Partnerships are emerging that help deliver new homes, with councils leasing land for build to rent and deriving a share of the income. Some understand this model, but others are nervous they may fall foul of government rules on best value.

The government should issue revised guidelines, which clarify that public sector land deals that might not generate the greatest instant profit but provide an income stream meets best value.

4 Reform the community infrastructure levy

The government is committed to reviewing CIL early in this Parliament.

Local authorities should consider a separate rate for build to rent in their charging schedules that reflects its different viability to build-for-sale.

5 Reform VAT, which hits build to rent far harder than buy to let

Rents do not incur VAT and therefore VAT on costs incurred by institutional investors has nothing to be offset against. For most buy-to-let investors this is not a problem as they are not VAT-registered. The 20% VAT paid on repairs and maintenance of build to rent property, however, eats into income and prevents investment.

Under the EU VAT Directive, the UK is permitted to reduce VAT rates to 5% on residential repairs and maintenance. This would give a long-term increase in the tax-take to the Treasury through increased economic activity, as well as on the construction of rented homes.

6 Make REITs work for residential

REITs seek to replicate the advantages of direct property investment for indirect investors, but to date the structures have almost solely been used for commercial property investment. Successive governments have made reforms to make REITs

more residential-friendly, but have not removed all of the barriers.

There is one reform that would help: REITs have tight restrictions on trading. This rule is aimed at commercial property, but as currently written is too restrictive and makes REITs an unattractive structure for residential investors.

7 Long-term stability

Build-to-rent investors will typically commit to investment for at least a decade. Therefore, they will weigh up longer-term risks, including political ones. This makes the tone of political discourse important. Measures such as rent controls and long-term security of tenure drove institutions out of the sector in the 1960s and 1970s.

The more there is a political, market-based consensus on the market rented sector, such as existed in the 1990s and 2000s, the more investment is likely to flow.

Click here to read the BPF’s manifesto in full and here for a map of PRS schemes