Lack of supply continues to drive house price inflation, and the gap between the property-owning haves and have-nots is a source of tension in some local communities.

Lack of supply continues to drive house price inflation, and the gap between the property-owning haves and have-nots is a source of tension in some local communities.

Growth was anaemic before 23 June. In the aftermath of the Brexit vote, the need for economic stimulus is greater than ever. And few investments have quite as powerful a multiplier effect as new home construction. That is the real reason housing was the focus of discussion on the floor at the Conservative Party conference.

Consensus is growing that we need to embark on the biggest programme of housebuilding in a generation. However, we are in danger of losing sight of the importance of quality.

Many large developments of the 1950s and 1960s became the sink estates of the 1980s. If today’s new housebuilding is not of sufficient quality, we risk repeating past mistakes.

The difficulty comes in defining what “quality” means.

Welcoming public spaces are vital. Proper amenities – transport, schools, healthcare – are needed to develop a community.

But to deliver the quantity of high-quality housing we need requires a coherent, overarching strategy.

The essence of that strategy must lie in diversity. Three things are vital to delivering quality new developments at scale: a mix of tenures, a mix of house types and a mix of development partners.

First, tenure. Unfortunately, debate about tenure is too often polarised between owner‑occupation and social housing. Such rigid distinctions are unhelpful. More importantly, by excluding the private rented sector, they are also outdated.

Millennials are happier to rent than previous generations. Almost by definition the PRS offers greater choice. If a development is not of sufficient quality, private tenants can and will move elsewhere. Diversity of tenure, including PRS units, helps drive up quality.

Second, a mix of house types is hugely important. Despite record demand, persistent under-occupancy of homes is a feature of today’s market. Many parents who have seen their children leave home and would like to downsize can’t do so because of a shortage of suitable properties.

Such inefficient use of existing housing stock is bad for individuals and a waste of resources. As the population ages, we need to cater for older residents moving back down the housing ladder.

Yet while diversity helps build strong communities, strong companies tend to be highly focused.

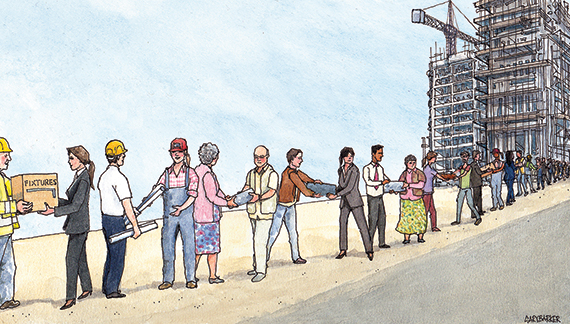

The answer to reconciling those conflicting forces is to work in partnerships.

Collaboration with the private sector in Birmingham means that we are currently able to meet demand for social housing in full. Just under 3,200 new homes were built in the city in 2015, 33% of which were affordable.

The national problem of housing shortage cannot be tackled by individual organisations acting alone. Effective collaboration is the only way to develop communities that are socially and economically sustainable over the long term.

Waheed Nazir is strategic director at Birmingham City Council