London’s housing market is in crisis. The bottom line? Many more thousands of new homes are needed. And quick.

Step forward pop-up resi: the slightly less conventional cousin to pop-up retail and offices.

Could prefab, or container housing, used for a temporary period of four to five years on large development sites – which sit unused while complex regeneration plans are finalised – ease the housing shortfall?

Opinion is divided. While the temporary homes could go up quickly and could provide an extra income stream to site owners and developers, and make government housing targets less out of reach, there is caution surrounding this fledgling trend. Planning issues are a major cause for concern.

Those in the positive camp include internationally renowned architect Lord Rogers, whose £4.3m Ladywell pop-up “village” in Lewisham is being hailed as a blueprint for such development. Plans include a cluster of 24 temporary homes that will stay up for four years, on the site of the demolished Ladywell Leisure Centre, before permanent homes are built.

The Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners designed scheme will be built using four-floor housing blocks which can be dismantled and reused in other locations. The scheme is aimed at providing a cost-effective alternative for families that would otherwise be placed in expensive B&Bs. Subject to approval, the first homes could be occupied as early as late summer this year.

Getting developers and local residents to buy in to the initiative, however, could be difficult. With this type of development comes issues surrounding infrastructure such as schooling and hospitals as well as utilities such as water, electricity and waste, let alone being able to evict people when developers want to get on and build permanent schemes on their land.

Julia Chowings, director, real estate advisory, at Deloitte, says that while she believes the initiative could be seen as a positive measure, not all sites will be suitable.

She says: “The temporary nature of the housing means that more flexibility can be given through granting planning permission for residential in locations that would not be acceptable on a permanent basis. That said, the sites still need to provide a level of accommodation and amenity suitable for the five years of occupation.”

Chowings believes that where sites already have planning consent for phased major development, the temporary use of the residential pop-up units should not undermine this overarching permission. She believes they are unlikely to require Section 106 contributions to education. However, there will still be a demand for services such as healthcare, putting stress on already stretched services. “A solution may be to agree a significantly reduced contribution, given the temporary nature of the impact,” She says, adding: “It will be interesting to see how CIL, both local and mayoral, would apply.”

One firm that is looking into the possibility of putting pop-up flats on big regeneration sites is Astudio. The architect is working with a contractor and has approached several developers.

Richard Hyams, a director at Astudio, says: “The demand for housing is so vast that clever solutions, featuring great design and lower costs, must be sought to deliver new homes quickly. This need is inspiring designers, architects, developers and manufacturers to produce first-class buildings and we look forward to announcing shortly what we have created.”

But not everyone is in favour of pop-up resi as a solution to the housing crisis. Adam Challis, head of residential research at JLL, says: “In our view, pop-up residential will struggle to be the next big thing.

“We have seen very little and there are still significant planning rules to overcome as residential requires a bigger set of parameters.” He adds: “I think it will always be a difficult sell to make pop-up resi mainstream.”

Challis says that while pop-up resi is an interesting idea, it still has a “host of challenges” and is quite different from the concept of pop-up retail. “There will be a significant planning overlay,” he says.

What is pop-up resi?

Pop-up resi differs from pop-up retail and offices, which tend to take space within existing structures. Pop-up resi involves building new, temporary structures out of modular blocks, prefabricated housing or converting shipping containers, to be located on cleared development sites.

Where could pop-up resi go?

According to EGi’s Residential Site Finder, local authorities are promoting schemes, including those that have yet to start on site, on around 439 sites across London.

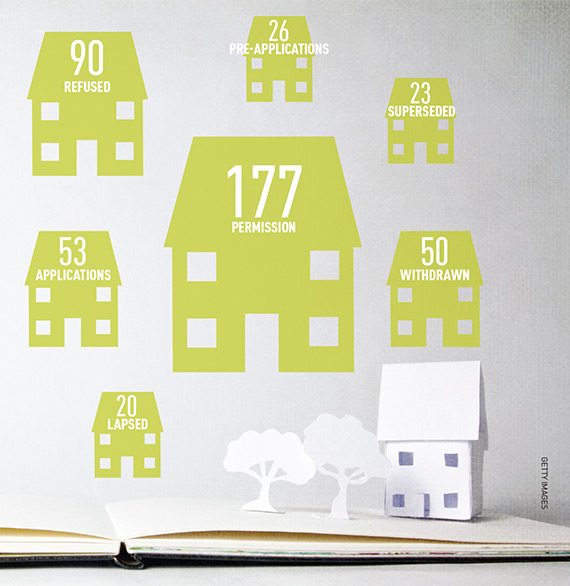

The sites are at various stages of planning (see graphic below for breakdown). Greenwich appears to have the biggest opportunity in London with 7,000 units proposed.

Paul Wellman, senior researcher in Estates Gazette’s London residential research team, says: “LRR research reveals there are 177 sites with planning consent across the capital on vacant land. Furthermore, 106 of those sites are where consent was granted in 2013 or prior, meaning construction has yet to get off the ground even though planning has been in place for some time. Could these provide further opportunities for like-minded councils to be proactive with willing landowners?”

Wellman adds: “Getting developers on side, however, could prove tricky if not impossible. Where it may work is where the local authority owns the land. But critics could have a valid point if they were to ask, “Is this just state-funded land-banking?”

lisa.pilkington@estatesgazette.com