Graffiti has kick-started the regeneration of entire neighbourhoods in New York and Miami. Could it have the same impact in London? And could the gentrification it creates blunt the artistic edge that makes it popular?

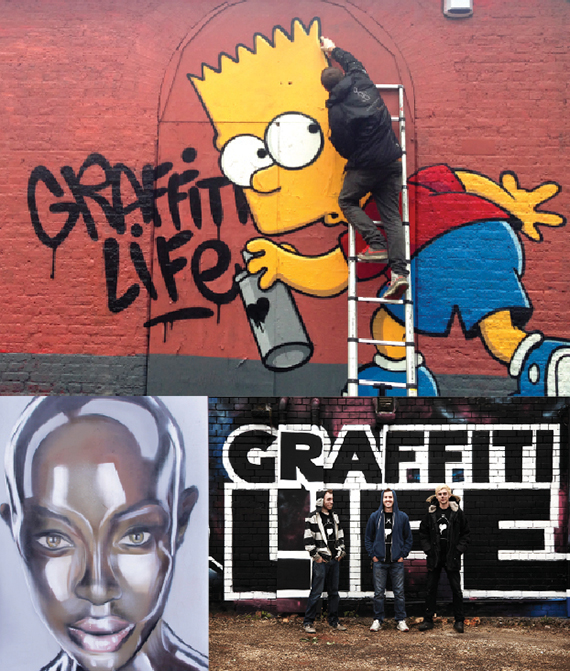

“How does something suddenly become cool?” London graffiti artist David Speed pauses for a second, pondering his own question. “I honestly don’t know if I will ever be able to answer that. Not in relation to graffiti anyway. Nothing about the way I paint has changed. The stuff I do that people want to buy now is the same stuff that they used to hate in the ‘90s. I have never understood why the perception of street art changed so dramatically. But it can only be a good thing.”

Just over 15 years ago, Speed was surreptitiously buying spray cans out of a car boot in Croydon and dodging police in and around east London to paint walls illegally in the name of creative expression. Today he is selling his work through his company Graffiti Life to the likes of BMW, Microsoft, Disney, Red Bull, Sky and even, here’s irony for you, the Metropolitan Police. “We don’t ever disclose how much we sell the pieces for,” he says. “And it is not like we are all filthy rich. But we make enough to run a company of 10 staff out of a decent-sized studio in a good London location now. This is purely thanks to selling something that people once saw as nothing more than vandalism. It is bizarre, and actually quite ridiculous, how popular street art has become.”

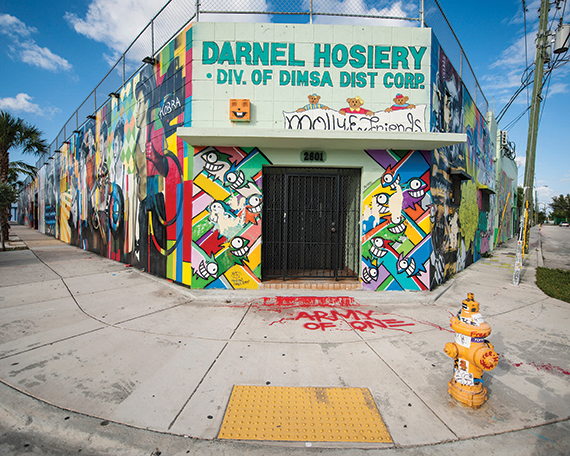

From the gritty, urban origins of graffiti in downtown New York to the famous curated murals in Miami’s Wynwood Walls district, the perception of street art has been gradually changing across the pond since the early 1990s.

To put that change in perspective, Wynwood now sees 150,000 visitors pass through in the first week of December for Art Basel alone. Commercial property prices in the area have rocketed from $10-$15 (£6-£10) per sq ft in 2010 to as much as $75. The hipster restaurants and artisan coffee shops have moved in and what was once a run-down, violent suburb is now a new, creative mecca.

It is the age-old tale: where the artists go, real estate value increases are often not far behind. But can graffiti, once more likely to be associated with a prison sentence than a pay cheque, be responsible for regeneration, even gentrification, in London? And is there a danger that if it continues to become increasingly mainstream it could lose the edge that is fuelling the current street art craze?

A catalyst for regeneration

When it comes to the power of graffiti as a catalyst for regeneration, there is no better example than Wynwood Walls.

Made up of 400,000 sq ft of old warehouse buildings once used by drug cartels to store cocaine in the 1970s, the walls are just one element of the wider Wynwood arts district – which includes 70 galleries, five museums, three collections, seven art complexes, 12 art studios and five art fairs.

When New York developer Tony Goldman bought the warehouses in the early 1990s to offer companies cheap storage space as South Beach prices skyrocketed, he took inspiration from the local graffiti artists. He started curating street art on the outside of each warehouse – wall by wall, door by door. And so the arts district was born.

“This used to be a ghost district,” says Wynwood curator Susana Baker. “Artists would come here to paint because they knew they wouldn’t be bothered. They still do paint outside the walls. But inside the walls those spaces are given to the top street artists in the world. They change every year for Art Basel week. We have had thousands of artists flying in over the years just to do a wall. Every building has become a canvas. And the walls are a collection. And like any art collection, it is always changing.”

The result of growing global interest and media attention around the district has seen it change dramatically over the past two decades. During that time, Baker says, it has seen its fair share of both winners and losers.

“It is amazing to see how the area has been lifted by the art,” she says. “We have a whole new demographic here now attracted by the galleries and high-end retailers. Landlords are able to charge significant rents and the vibe is very Soho/Chelsea. For some artists this has been fantastic. Tag names were always used in the past as people were worried about being arrested. Now these artists can use their real names, they are getting known and can sell their pieces because they are not afraid to make a living from their art.

“Of course, there are others who are behind that curve who are being priced out. But that is part of a constant, wider patter. And it is the beauty of art. It is very fluid. And artists will continue to regenerate areas. Fifty years ago Coconut Grove was the creative district. Then the artists were priced out and moved to South Beach. Then Gianni Versace bought a house there and they were priced out again. Then they moved to Wynwood and now they are being pushed out to Little Havana and Little Haiti where there is, as yet, no major retail. It is cheap and there is still a degree of economic hardship. These areas will become the new wave for the next decade or two of regeneration. All thanks to these artists. It is an amazing pattern.”

So what, if anything, can we learn from this here in London?

A UK graffiti district?

While the chances of creating a carefully curated graffiti district to rival Wynwood in the UK capital seem unlikely, there are examples of existing street and public art areas being protected in the name of cultural regeneration. Brick Lane, E1, and Leake Street, SE1 – the latter is known as “the Banksy Tunnel” and set to be the location for a new restaurant quarter – are just two areas that have built up a popular cultural identity around street art. And the Banksy-adorned Millennium Mills building on the site of developer First Base’s Silvertown Quays site in east London has been heralded as the lynchpin that will cement the development’s status as London’s new creative district (see p22).

“If you embrace it properly and are prepared to have an open mind, graffiti can really add value to a development,” says David Rosen, senior partner at Pilcher Hartmann. “For example, the graffiti on the Millennium Mills buildings adds an entirely fresh level of history and authenticity.” [See box overleaf for more on the legal complexities surrounding the value of street art for property owners.]

“Increasingly people want to see some creativity around them,” adds Ross Bailey, founder of retail pop-up company Appear Here. “We don’t all necessarily want to be surrounded by the same glass buildings any more. If a fresh, authentic vibe comes from a piece of street art, why not?”

And Graffiti Life’s Speed adds that as graffiti has become increasingly accepted as a form of art rather than an act of vandalism, it has developed into a much more powerful catalyst for the regeneration of entire areas in London: “It has always been the way that things happen that artists will move into an affordable area, create art there that makes the area look better so everyone else starts to follow until the artists are priced out and move on. It’s just that now street art is part of that equation in a way it wasn’t until relatively recently.”

The price of going mainstream

But what happens when something that is arguably all the more attractive thanks to its gritty, underground reputation becomes mainstream? Does it lose its value along with its edge? Is there a danger that the London street art craze will be just that – a bright but fast-burning trend that could undermine the authenticity of the older, original statement pieces in and around the city?

“There is an argument on both sides,” says Pilcher Hershman’s Rosen. “On one hand, I think modern graffiti needs to be part of a very loose structure rather than a free for all. But is there such a thing as controlled freedom of expression? The essence of graffiti is that there are no controls and there is no structure. It is difficult to come down on either side of that debate.”

It seems that many graffiti artists would rather have the chance to paint in legally sanctioned, safe areas – as was the way in London in the early ‘90s – than not at all. And an active campaign to support legal graffiti rather than ban it completely would be the preference of most people looking to create art rather than paint as an act of rebellion.

“It is when there are no areas left to use as canvases that our hands are forced,” says Speed. And he shrugs off any concerns that growing popularity around street art could make it too mainstream to maintain an edge.

“As long as I know I am pushing the boundaries of what we are doing here visually then I just don’t get caught up in those debates. I would drive myself mental if I started worrying that what we are doing is now getting too popular. And you just have to look at Instagram to see how growing interest around street art is pushing more, not less innovation. People wake up around the world, log on and can scroll through their accounts and see hundreds of new ideas, new designs and new styles form all around the world. The result is everyone trying to get one up on each other. And that drives everyone forward.”

“Street art is an expression of political history,” adds Wynwood Walls curator Baker. “That is the case whether you are talking about the past, present or future. Like all art, it is a form of conversation, to engage with people through the murals. And for that reason alone there can be nothing bad about the shift from this being a worldwide underground movement to one that is out in the open for everyone to see. All eyes are on street art now. Which is the way it should be.”

Who owns graffiti?

Charlie Winckworth, IP partner, Hogan Lovells

Banksy, the controversial graffiti artist, is perhaps unique in his ability to attract widespread praise for acts of criminal damage. With an estimated net worth in excess of $20m (£13m), and a loyal following of fans, he’s doing well for himself. But others are too.

In 2012, a pound shop in Haringey removed a Banksy mural entitled Slave Labour (Bunting Boy) from its wall, and sold it in the US for £750,000. In 2014, a Brighton pub pocketed £345,000 when it sold part of its external wall that featured a mural entitled Kissing Coppers. And a mural entitled Girl with Balloon was removed from a wall in east London and sold. A Banksy in its original location is now as elusive as the artist himself.

So are these lucky property owners allowed to profit from Banksy’s work? In short, yes. Although the property owners do not own any intellectual property rights in the graffiti, the physical artworks – like the walls they are attached to – belong to them. The property owners are therefore at liberty to admire them, paint over them, or rip down their walls, ship them to Miami and sell them to the highest bidder. Planning, PR and local community concerns aside, of course.

However, the ownership of the copyright in the graffiti is a different matter. Under English law, copyright subsists automatically in any original artwork that uses the artist’s skill, judgment and individual effort. There is nothing to be registered. Even Banksy’s fiercest critic would have to agree that his graffiti passes this test. Banksy is the owner of the copyright and can therefore sue anyone who copies his artwork. He also owns the “moral rights” in relation to his artworks, which means he can, among other things, object to derogatory treatment of an artwork. Arguably this extends to the people defacing his artwork (something that has happened regularly), although whether the courts would enforce moral rights in relation to illegally created graffiti is another question. Perhaps the defacing is itself a form of art?

For now, it seems that Banksy is happy to live by his mantra that “Copyright is for losers©™” , and there appears little prospect of him trying to enforce his copyright or moral rights in his graffiti. And remember, before you call the police on your neighbourhood graffiti artist, check it isn’t Banksy.