“When you are rebuilding after tragedy, you have to face the trauma head on,” says Daniel Libeskind. “You can’t hide a city’s scars. There will always be memories. You have to turn them from something negative into something positive.”

There are few people who understand the power of reactive placemaking better than the architect behind the redevelopment of Ground Zero in New York following the 9/11 terror attacks. A scheme that was not pre-planned as part of a wider, strategic urban regeneration, Libeskind’s Ground Zero masterplan was instead born out of unanticipated pain and grief. But it was this project, he says, that made him realise just how cohesive and healing the right approach to city design can be.

Conversely, he is quick to point out that the wrong design can have just as much power over cities and the people living and working within them. He has been quoted as saying that “misogyny is built into society” and has implored his peers to think differently about urban planning, pointing out that architecture “should not always be comfortable”.

As he gears up to redesign the Museo Regional de Tarapacá in northern Chile, dedicated to pre-Hispanic history dating back 6,000 years, Libeskind explains why embracing the real character and history of a place – flaws and all – is the only way to build spaces that are truly designed for everyone.

Career-defining projects

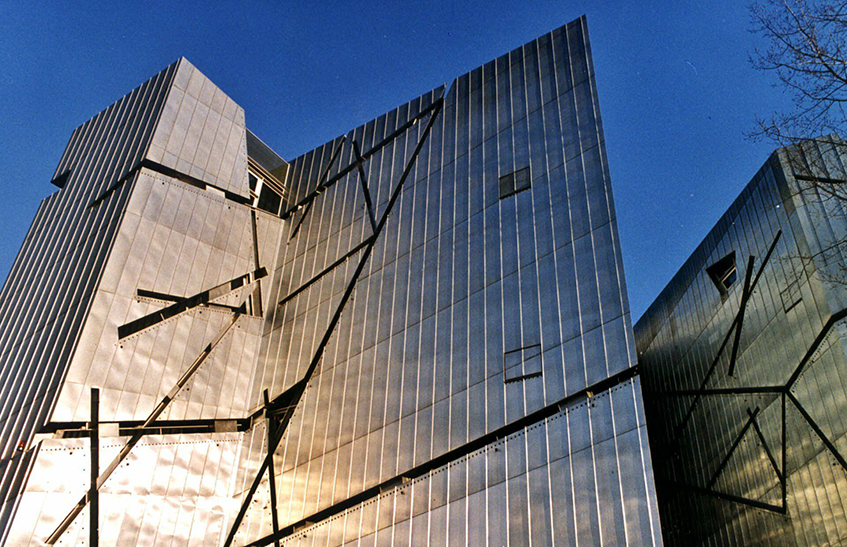

This approach was at the heart of his Ground Zero masterplan. This scheme, along with the Jewish Museum in Berlin, are the projects the 72-year-old Polish-American architect has become best known for since setting up his practice, Studio Libeskind, with his wife Nina 30 years ago.

After the planes hit the Twin Towers in September 2001 and a vast chunk of New York’s previously bustling financial district was decimated, it wasn’t buried just by the physical rubble and destruction but also by the memories of such a tragic event.

When Libeskind was brought on board by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation in 2003 to masterplan the 16 acres that had been damaged or destroyed, the recovery effort seemed almost futile – at least from a commercial perspective.

“When I first started working on the scheme, people had lost all hope,” he says. “Most of the companies had moved out of the area by the time I arrived, and there was a genuine assumption that this part of the city would never come back to life and that commercial space would have to be given away for free. Everyone had left and people thought that would be the end.”

Nearly two decades on, this prediction could not be further from what has actually unfolded at and around the site of the attacks. The area is well on its way to becoming a thriving business district once more and has attracted high-profile tenants, including Condé Nast, Spotify and Zurich.

Not only that, but Libeskind’s “Memory Foundations” masterplan, which includes the two memorial pools marking out the footprint of each of the original towers surrounded by the new World Trade Center skyscrapers, attracts visitors from around the world. The result is a bustling neighbourhood that does not shy away from what happened there in 2001.

“It had to be respectful and forward-looking at the same time,” says Libeskind. “I wanted to create a bridge between the memories of what happened and the future”. The result, he believes, is that Ground Zero has become “the new centre of New York” against the odds.

“There is no doubt that over the next 30 years, [Lower Manhattan] is where all of the development will take place in the city, from culture to retail and from hotels to schools,” he says. “When you think that 250,000 people have moved to Ground Zero since I started working on the project, that shows that even a site associated with something so tragic can become the fulcrum for a city’s development.

“I believe that comes from following a masterplan that concentrates on public space, amenities and transportation, but crucially a plan that does not shy away from the memory of what happened on that site.” He adds that it is not just about a passing reference, either. “I never wanted the history of the site to be an aside, a footnote. It is the central theme of the plan.”

But Libeskind is quick to add that, as successful as the Ground Zero masterplan has been, there is no room for replication in urban design.

The soul of a place

“There is no formula,” he says. “It is not just about infrastructure and engineering. It is about reacting to culture and the humanistic elements of a city. And when you touch on these roots, you reach the soul of a place rather than just its body. That is the key to great urban development, it is about spirit. Of course, that drives the buildings and everything else surrounding those buildings, but I would never start with the concrete blocks. For me, it has to be the other way around.

“I have said in the past that architecture shouldn’t necessarily be comfortable. By that I mean we shouldn’t be falling into old patterns of what has worked in the past. You can say ‘we did that project this way and it was really successful’, but that’s not always the right approach. We need to be innovative and break new ground because times are changing and people’s desires are changing. Architects should be leading these changes, not lagging behind.”

This is where his thoughts around misogyny being “built into society” are particularly relevant. Stemming from a comment he made condemning the “generative prejudice against women” within the architectural profession, Libeskind says that this imbalance can be seen in the resulting physical built environment.

“I am a great believer in democracy being the only starting point from which you can build really interesting places for all people,” he says. “But that democratic process is flawed – and not just in relation to a gender imbalance. Access to the built environment and the world we live in has to be given to everyone, and we must not fall into those pitfalls of catering to this group or that group.”

As to whether he sees enough acceptance of the changing nature of design, and inclusive design more specifically, Libeskind hopes a turning point has been reached. “We are going through an evolution,” he says. “For so long, architects have sat in ivory towers and suddenly a building appears on a street or as part of a place and no one really knows or understands the drive behind it. That’s not my type of architecture – I don’t like design that has that sort of authoritarian streak. It all goes back to responding to needs, and creating great spaces that are not just built as an exercise of power.

“Ultimately, architecture is political, and we should all be aiming to design something for the citizens. I do see more of that now – more open-minded design. I just won a project in New York for social housing for the elderly, for example. We need more of this, more plans where glorious buildings in amazing cities are not just kept back for people who can afford them. This creates a sense of social justice in a city; it is an ethical approach that allows everyone to share. I really do believe that if a city is not equitable, it will fail.”

Are there any exceptions? Not by Libeskind’s standards for what makes a successful city: “Where there is a lack of social justice, cities become unsustainable,” he says. “Without equitable distribution, they are not places for everyone. And it is important we remember this, because cities are in competition with each other now more than ever before. It is not country versus country anymore. It is city against city, and the race is on.”

Libeskind’s life and major works

Daniel Libeskind studied music at the Łódź Conservatory in Poland, before moving to New York in 1960 on a music scholarship. He began to study architecture soon after he arrived under John Hejduk and Peter Eisenman at Cooper Union.

In 1989, Libeskind, who lost family in the Holocaust, won the competition to build an addition to the Berlin Museum that would house the city museum’s collection of objects related to Jewish history. Despite a decade of opposition, the building was completed in 1999 and opened as a museum in 2001. A space known as the Void – a path of blank concrete walls – runs down the length of the structure which visitors can see but not enter. This is a design feature to suggest absence and paths not taken.

On the back of this project, Libeskind secured a number of museum commissions in the late 1990s and early 21st century, including the Imperial War Museum North (1997-2001) in Manchester. He has also worked on a number of Jewish projects including the interior of the Danish Jewish Museum (completed 2003) in Copenhagen, a glass courtyard (completed 2007) for the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the Contemporary Jewish Museum (completed 2008) in San Francisco.

In 2003, Libeskind won an international competition to rebuild the World Trade Center site in New York.

Main image © Agencja Fotograficzna Caro/Alamy Stock Photo

To send feedback, e-mail emily.wright@egi.co.uk or tweet @EmilyW_9 or @estatesgazette