What would the world look like if, as an architect, you could tell people what to do?

“I’d like to think it would be a better place,” says Lord Norman Foster. “Because design – and I mean enlightened design – can make a difference for good.”

It is a comment on the profession so simple, so pared back and so innocuous that from almost any other architect it would sound tediously predictable. Even a little trite. But Foster is not any other architect.

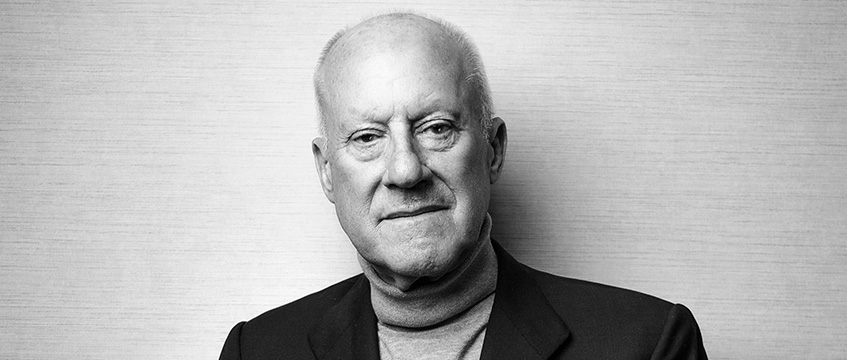

One of the most prolific designers in the world, the 81-year-old has a reputation that stretches beyond the boundaries of the industry’s often impermeable inner sanctum. Respected and revered by many outside the design community as well as those within it, he has reach and kudos that mean people listen when he speaks. And that, he concedes, is a huge responsibility.

“There are important messages to get out there,” he says. “So I feel a responsibility to use powers of communication. And in different ways: through my work as a designer, through leading other designers, by creating teams, by giving talks. I want to get certain messages out to younger generations, too. In a way, it is like being a juggler trying to balance it all.”

Some of those messages address the barriers Foster is desperate to break down between the architecture, construction and property professions. Others are more ambitious: tackling humankind’s intrinsic fear of change, for example. Then there are those that relate to frustrations hinted at earlier around being unable to “tell people what to do”. But while this might be the case when it comes to how he views the “powerless” role of designers in the life cycle of a project, on a wider scale it does not hold water. Because Foster wields power on a significant scale. The man behind schemes including The Gherkin, Wembley Stadium and Apple Park in California sets an architectural tone that is as influential as it is iconic.

And in the year his practice, Foster + Partners, celebrates its 50th anniversary, his latest project is about as high-profile a stake in the ground as you can get.

The 175-acre Apple HQ campus in Cupertino, California is the office project the rest of the world will look to for inspiration. Originally the brainchild of the late Apple chief executive Steve Jobs, who brought Foster on board right from the outset, the £4bn, ring-shaped building dubbed “the spaceship” is due to complete later this year. As the name suggests, Apple Park will be surrounded by green space and parkland, will be carbon-neutral and is set to be one of the most energy-efficient buildings in the world.

Orchards

A central courtyard in the middle of the main building will be filled with apricot, olive, and apple orchards. All plants selected for the campus landscape are drought-tolerant and there will be 9,000 trees and 309 varieties of indigenous species on site. The solar panels installed on the roof of the campus can generate 17 megawatts of power, making it one of the biggest solar roofs in the world.

It is all of this, says Foster, that lies at the heart of future occupier demand, as sustainability is considered just as important to the modern tenant as the provision of the on-site Apple store or the size of the desks in the open plan workspace: “Young people will choose office buildings based on facilities and lifestyle but they are also very aware of climate change and sustainability,” he says. “Future generations will be much more demanding, much more questioning of what a potential employer will be doing in terms of combating climate change. So I think what you are seeing is a transfer where creating good-quality working environments, which are more responsible in terms of sustainably, is good for business and is good for all the things that are important to industry.”

But he adds that the drive to deliver on these standards doesn’t always come from the developer. As a rule, they just “follow the market”. Only some are “leading the way”. Instead he credits “entrepreneurs and enlightened individuals” as the catalyst behind design and construction progression.

Apple Park, where Jobs had a clear vision for the scheme and is reported to have asked to be considered one of the team rather than the client from the outset, is a case in point. “The overall trend is that it is very much the entrepreneurs pushing new ideas forward,” says Foster. “Apple Park, which is nearing completion, was initiated by Steve Jobs then carried on by [chief design officer] Jonny Ives and his team with the support of [chief executive] Tim Cook. So there is continuity there.”

Foster adds that these sort of projects, inspired by creative chief executives and other innovators, are setting much of the agenda when it comes to modern building design.

“We have all these ideas for buildings coming out of very different individuals and organisations,” he says. “And I have no doubt whatsoever that many of these ideas will have found their way into mainstream developers’ buildings because we are all a product of our influences. Some of those are manifest and obvious; others are most subtle and self-conscious.”

Competition for talent

It is true that, as the competition to attract the best talent rages on across tech and corporate companies alike, much of the fresh, forward-thinking office design that has infiltrated mainstream commercial buildings stems from inspiration drawn from the Googles, Facebooks and Apples: “There is more demand and standards are being raised in terms of levels of tenant expectation,” says Foster. “To attract the best people, you have to provide the right facilities. Instead of one party being desperate for a job and taking one at any kind of price in any kind of surroundings, more and more sectors are seeing talented young groups of people who will pick and choose where they work based on the quality of the environment.”

Still, he says, people don’t always listen. And herein lies that frustration of feeling like he is not in a position to tell people what to do. “What I mean by that is this: in an ideal world, an architect would be able to create a whole building,” he says. “So I could say, for example, I have a passion about this aspect of design and so I am going to just take this site here and I am going to create a building for 5,000 people to work in and that building will demonstrate what I believe in.”

An architectural utopia dashed, presumably, by a pesky developer pulling in the reins on boundless creativity? Or sidelining the designers and the artists until the last possible minute?

Not exactly, says Foster. But he does believe that operating in silos is a major blocker to communicating creative ideas. “If you are a developer and an architect, you can do what you want,” he says. “But as just an architect, the point I always make is that I can’t tell people what to do. I can’t direct someone and say ‘build it like this.’ That is why we need to break down the barriers between the professions and bring all the different skills together to interact creatively. We need to encourage inter‑disciplinary thinking.”

Deep distrust?

He adds: “In some sectors there is still a deep distrust of those who actually make it possible to realise a building. Bringing those people, such as artists, forward to the beginning of the process and making them active participants in the process through a round-table approach is not designing by committee. It is bringing all the skills together at the outset.”

And while resistance to this sort of progression is commonplace – especially in a traditional industry such as property – standing still is something Foster himself has always been careful to avoid. It is a strategy that has served him well. His ability to move with the times is one of the reasons he has attracted and retained such perennial interest from both professional peers and public onlookers. He is well versed on the impact AI, robotics and machine learning could have on the future of design, he joined Instagram in his 80s and Foster + Partners is renowned for being at the cutting edge of technological advances – and has been since it was set up in 1967.

“My motto is that the only constant is change,” he says. “I think that probably sums up the story of everything. Memories are short but still I think that often when you adapt, it is not seen as a change for good. Which is not the case. I can understand there is a natural resistance to it because of the uncertainty. But the whole story of society, since we came out of the cave, is about change and progress.”

What about advances such as 3D-printed buildings? Is this the future or a move away from the true essence of creative individualism?

“I think that, if properly harnessed, 3D printing offers a lot of opportunities,” he says. “The downside would be more mindless repetition, or intrinsically bad practice and designs. But I would take a more optimistic view and say it offers the potential for greater customisation and greater creativity. Of course it raises some very big social issues. If you are able, through robots and artificial intelligence, to do things quickly and efficiently that are otherwise very labour-intensive, then that’s liberating in one sense. There are then issues over the future of that labour force – but historically these sorts of changes have resulted in higher levels of education and a more productive redeployment of labour.”

Learning lessons

But just as change and moving forward is a crucial driver to survive in fast-evolving times, so, too, is looking back and learning lessons from the past.

Now, 50 years since he founded his practice and nearly 60 since he won a place at the University of Manchester School of Architecture and City Planning, Foster says he relies heavily on the benefit of hindsight.

“I think, when you get to a point where you can look back at life over a longer period, you realise that there are these cyclical trends that go beyond property and finance. So you have these ripples and some of the ripples we are all seeing at the moment are political. But honestly, I think, in the grander scheme of things, if you look back in 10 years’ time, even five years’ time, it won’t seem the big deal it does at the moment.”

Reassuring perhaps, but a tall order to persuade people to blindly embrace the benefits of Foster’s personal hindsight in the midst of severely uncertain times.

If only he could tell people what to do.

A life in architecture

Foster was born in Manchester in 1935. After graduating from Manchester University School of Architecture and City Planning in 1961, he won a Henry Fellowship to Yale University, where he was a fellow of Jonathan Edwards College and gained a Master’s Degree in Architecture. In 1963 he co-founded Team 4 with Richard Rogers and in 1967 he established Foster Associates, now Foster + Partners.

He was awarded the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture in 1983, the Gold Medal for the French Academy of Architecture in 1991 and the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal in 1994. Also in 1994, he was appointed Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters by the Ministry of Culture in France. In 1999 he became the 21st Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate; and in 2002 he was elected to the German Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste and in Tokyo was awarded the Praemium Imperiale. He was granted a Knighthood in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List in 1990, and appointed by the Queen to the Order of Merit in 1997. In 1999 he was honoured with a life peerage in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List, taking the title Lord Foster of Thames Bank.

Picture © Will Bembridge

To send feedback, e-mail emily.wright@egi.co.uk or tweet @EmilyW_9 or @estatesgazette