Ireland’s economy is heading for the skies. Literally. Earlier this month Dublin Airport confirmed that it will start work on a second 10,200 ft runway that should be operational by 2020.

Ireland’s economy is heading for the skies. Literally. Earlier this month Dublin Airport confirmed that it will start work on a second 10,200 ft runway that should be operational by 2020.

The £259m project originally won planning consent in 2007 but was then grounded on the tarmac due to the global recession. Since then, passenger numbers have ricocheted back to a record 25m in 2015 (higher than the 23m recorded at both Manchester and London Stansted).

The significance of the new runway to Ireland’s economy isn’t lost on the minister for transport, tourism and sport, Paschal Donohoe, who confirms: “It has the potential to create thousands of jobs, both directly and indirectly, over the coming years.”

Many of those are likely to be with the corporates who have made Ireland their European home because of an extremely friendly tax regime (see below).

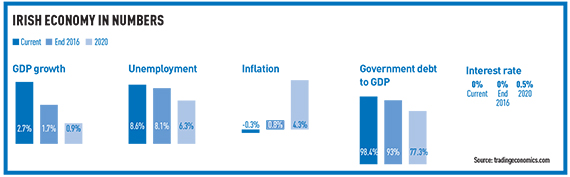

GDP forecasts this year vary from 5% to less than 3%, but Dublin economists expect Ireland to be the best-performing economy in Europe for the third year running. Less loudly, they acknowledge that one of the reasons for the impressive performance is the country is coming from a low base, after taking a heavy knock during the downturn. Nevertheless, there is no denying the recovery has been impressive, even if future growth will be more modest.

“The economy is now 10% bigger than it was in 2007, though the same isn’t true for employment – we’ve only recovered half of the 346,000 jobs lost between the last peak and trough,” observes John McCartney, research director at Savills.

The good news is that those jobs appear to be coming back, even before Dublin’s second runway is finished. “Positive employment growth should be forthcoming,” confirms Annette Hughes, director of Dublin-based economic consultancy DKM, though she notes that wage demands – which have been getting louder since the austerity cutbacks – may dampen future growth.

Just before it was dissolved ahead of February’s election, the then-government published a capital plan outlining a strategy for Irish economic progress. With the formation of a new government in limbo [see box below] it is not clear whether that plan will be taken forward, though so far economic commentators have been relatively relaxed about the hiatus. They are more concerned about the prospect of the US presidential elections, and a Trump presidency in particular, which could have an impact on future FDI demand from US companies.

For now, though, physically finding new offices is more of an issue [see offices, right] – as is the ability to house Ireland’s growing population.

“Housing is possibly the number one issue for the Irish economy and for the new government to tackle,” says Marie Hunt, head of research and executive director at CBRE.

A shortage of stock, exacerbated by lack of provision of social housing for an extended period, will not be rectified in the short term. Developers may start building in greater volume later this year when planning regulations are relaxed to allow greater densities. However, Hunt says they will still be looking for government assistance, such as a reduction in VAT on new construction from 13.5% to 9%.

A shortage of stock, exacerbated by lack of provision of social housing for an extended period, will not be rectified in the short term. Developers may start building in greater volume later this year when planning regulations are relaxed to allow greater densities. However, Hunt says they will still be looking for government assistance, such as a reduction in VAT on new construction from 13.5% to 9%.

That may well happen, as the previous government lopped off a full 50% of corporation tax in the last budget. A new government is also expected to maintain a commitment to a steady reduction in the budget deficit, which until the end of last year was running at over 100% of GDP. “Government debt is a key issue, though exports are also really important – they kept the economy afloat during the recession,” notes John Ring, investment analyst at Knight Frank. They could also be hit hard by Brexit [see box, previous].

Savills’ McCartney points out that the low interest environment common across EU member states may be beneficial for Irish property. “With an interest rate rise still a long way off, investment flows will be inclined towards commercial real estate for some time,” he says.

So, no need for anyone to fasten their seatbelts just yet.

Corporation tax

If anyone thinks Ireland is likely to easily give up the considerable presence of multinationals it has fought hard to attract over the past couple of decades, they should think again.

Last autumn’s Irish budget sent a very clear message: businesses will be looked after in Ireland. The country’s already low corporation tax of 12.5% was halved to a jaw-dropping 6.25% – though only for companies with specific types of R&D operations. The move contrasted sharply with the ambitions of other EU member states such as France and Germany (where corporation tax is around 33%) to introduce a minimum tax level in all member states.

In the past 12 months, the Irish government has responded to accusations from both EU members and US politicians that it is effectively a tax haven by introducing new, tighter corporate reporting legislation, following the closure last year of the so-called Double Irish tax loophole.

The greatest potential suitor to Ireland’s coveted global firms is the UK, where corporation tax will drop to 18% by 2020, and in particular Northern Ireland, where the same tax will be slashed to 12.5% in 2018, matching that in the Irish Republic.

“We should be concerned about this, as we could lose some FDI to Northern Ireland, especially as wage costs, house prices and commercial rents are considerably lower there,” says CBRE executive director Marie Hunt. Other Dublin commentators agree and warn of the danger of a race to the bottom on corporation tax.

However, Hunt points out that businesses will often have particular reasons for choosing the Irish Republic, including the desire to be euro-denominated.

Brexit

With nearly two months before British voters decide whether to stay in the EU, Irish commentators are undecided on what effect a Brexit might have on the country’s economy. “It’s an imponderable, though studies suggest it may be bad for Ireland,” say Savills research director John McCartney.

Irish business group Ibec has attempted to sort fact from fiction and identified the main risks. Top of the list are exchange rates, overall trade and investment. If the UK decides to cut ties with its EU partners, it would need to negotiate trade agreements, a process that could take two years. “This would bring a level of uncertainty for Irish firms exporting to Britain in the short term, impacting on employment, investment and export plans,” notes Ibec in a briefing report published in March.

However, there are potential upsides. Dublin could expect to be a major beneficiary of multinational firms wanting an HQ within the EU. Other countries, notably Luxembourg and Germany, would also have their eye on this prize, and the main challenge for Dublin would be finding office space to accommodate a sudden influx of occupiers.

Just how large the exodus from London might be is dependent on the UK’s ability to persuade firms to stay – and unconstrained by EU state aid rules, it is almost certain that those threatening to leave would be offered an attractive incentive to stay put. “But the biggest threat right now is the sheer uncertainty over what will happen,” concludes Knight Frank director Adrian Trueick.

Dublin office market

While the Irish economy may be cruising, Dublin’s office development market is reaching skywards.

While the Irish economy may be cruising, Dublin’s office development market is reaching skywards.

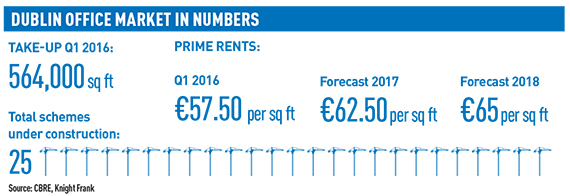

In the first quarter of this year, more than 1.3m sq ft started construction, bringing the total number of schemes currently under way to 25. Admittedly some is prelet space, but the sheer volume indicates the extent of unfulfilled demand in the Irish capital.

At present, new schemes are entering the pipeline each week. One of the most visible – assuming it goes ahead – will be The Exo in Dublin’s Docklands. Still in receivership, the 225,000 sq ft office tower won planning consent last month and, at 240ft, will take the crown as the city’s tallest building. Docklands is one of the few parts of Dublin not subject to height restrictions.

For now, arguments about whether multinational firms are more or less likely to take space in Dublin are largely academic as the first big chunks of new space won’t complete until next year.

“Vacant grade-A space in Dublin 2 and Dublin 4 is virtually non-existent,” says Knight Frank research analyst Robert O’Connor.

And even though cranes are now dominating the skyline, there are question marks about how much supply will be absorbed by the new buildings. “Our calculations suggest that there isn’t enough space to meet demand caused by employment growth,” adds Knight Frank capital markets director Adrian Trueick. “Funding is the main issue. It’s difficult to get bank funding, even with a prelet.”

Occupiers wanting to move are faced with two choices. One is to choose space in the suburbs; the other, says CBRE executive director Marie Hunt, is to commit to a new-build. “Prelets are likely to become more prevalent as occupiers can see that delivery dates are realistic,” she says.

Opting for a prelet is also a savvy way of avoiding rocketing office rents. Savills research director John McCartney says Dublin rents are moderately inelastic – as they go up, demand doesn’t fall off significantly – so price rises will have a limited effect on occupier appetites.

New Irish government

As EG went to press, Ireland seemed to be heading for a minority government, led by the existing taoiseach (prime minister) Enda Kennedy. An agreement between the two majority centre parties Fine Gael and Fine Fàil would bring to an end the bickering that has replaced political leadership since the general election at the end of February.

The pause in government caused by the failure of either large party to gain a majority or to form a coalition with others (as has been the case for nearly 40 years) has so far raised remarkably few eyebrows among economic commentators in Dublin.

But if a resolution isn’t agreed soon, public confidence might start to waver. How the eventual formation of government will affect economic policy isn’t clear, though any major shifts in direction are unlikely. The independent TDs (MPs) who could yet become part of the new government are generally to the left of the two largest parties, so their influence could bring minor tweaks to future economic strategy.