The best way to enliven any discussion about the historic environment is to mention English Heritage’s role in the identification of the best of the recent past for listing.

The best way to enliven any discussion about the historic environment is to mention English Heritage’s role in the identification of the best of the recent past for listing.

It evokes strong reaction and usually exposes the “aspic” criticism at an early stage. This is particularly true in the case of property professionals and those who still do not recognise that listing does not prevent change but acts as a signal to indicate that such change needs to be thoughtful.

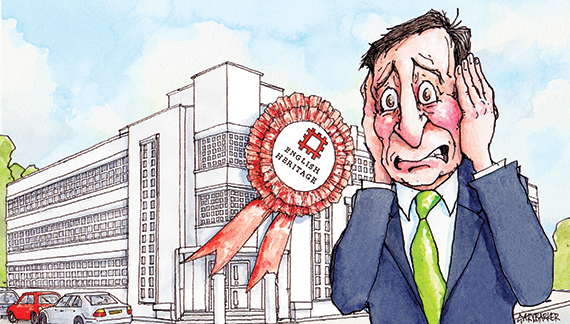

A building can be considered for listing once it is over 30 years old, unless it is facing threat of imminent demolition by which time it may have already gone through adaptation, particularly if designed for commercial use. However, a clear consensus on its enduring qualities will not usually have emerged. But raise the idea of listing and you are regarded as naïve and potentially an enemy of economic growth. A recent example occurred with the news that an EH strategic designation project was in place to identify the best post-war commercial buildings for listing.

The rapid pace of change is such that English Heritage has to identify what is the best of recent architecture. Backed up by careful research, a list of commercial buildings was drawn up, then whittled down for detailed examination.

Some of the final list are located in London, which is not surprising given the significance of the 1980s’ “financial Big Bang” and the conscious reshaping of the City undertaken since the second world war. However, the confidence which drove this dramatic change seems to evaporate in some minds with the suggestion of listing. Some claims that designating a small number of the best would bring the financial heart of the country to a standstill were made in all seriousness. This was despite only two dozen buildings nationally making it onto the shortlist.

It was also despite the fact that Lloyds of London has recently become Grade I listed, with a list description that is meticulous in identification of its special qualities, in explicit recognition that it had been adapted and would continue to change. Some commentators even suggested contemporary commercial buildings in the City be designed to ensure they were not good enough to meet the listing criteria.

Pause for a moment and consider that suggestion. Instead of attempting to create places of enduring quality that might receive the accolade of listing, their argument is that the quality of the physical environment is a secondary consideration for financial or commercial services.

Thankfully when I visited the Corporation of London recently it demonstrated a pride in many of its recent achievements in post-war planning and while concerned about the issue of setting, recognised that high design quality is a competitive advantage. It was implicit that the tradition of commissioning great buildings should continue. It is therefore surely unthinkable for us not to be aiming to add our contribution to the National Heritage List for England and the story it represents.