Since moving to London, I have often romanticised about living on a houseboat. While cycling to work along the canals, I would find myself observing life on board, envious of the tranquillity and stripped-back living I imagined residents enjoyed.

I was particularly excited then, when, as part of this Lowe Cost Living investigation, I managed to find a suitable vessel, for under £500 a month, on which to spend three weeks. My overarching discovery? Renting on a houseboat is not exactly plain sailing.

Although it was only a short stint and I was fortunate to be on a boat in mid-August, I still encountered my fair share of ups and downs. From glorious evenings spent cruising along the towpath on my bike, to waking up in the middle of ?the night to find our boat had come loose of the mooring and was drifting down the canal crashing into anything in her way. It was eventful, to say the least.

The first major hurdle I found was actually finding an affordable room on a boat in the first place. Larger boats on private moorings were way out of my budget, coming in at an average of around £1,200 a week, so I took to east London’s extensive canal network in search of a bargain.

With narrow boats rarely boasting more than one bedroom and boat owners cautious to rent to a “newbie” with little boating experience, my options were limited. I was advised to post on a popular online forum requesting some help in my mission to locate a boat. Unfortunately my plea was met by a barrage of abuse from seasoned boaters who took great joy in telling me how convenient it was that I was looking to rent in mid-summer and that I simply didn’t understand the hardships of boating in the midst of a cold, damp winter.

Not a great start but understandable, I suppose.

Knocking on cabin doors

Undeterred, I got on my bike and took to Regents Canal, knocking on cabin doors to see if anyone would have me. Fortunately it wasn’t long until I was lucky enough to meet Dave, a canal boat owner, who had moored up along Victoria Park in Hackney. Priced out of the housing market and inspired by a recent boating trip, Dave had decided to take the plunge and purchase his very own floating home. ?After doing some research, Dave opted for a wide-beam, which is similar in length ?to the common narrow ?boat but double the width, giving him 500 sq ft to play with. The added advantage ?was that he could create an extra bedroom to rent out.

Wide beams are surprisingly cheap to buy; for a brand new hull and engine it will set you back around £40,000, and a further £20,000 to fully furnish it. Although you can pick up a secondhand narrow boat fully furnished for around £25,000, they do not offer the space a wide beam will. On paper, this is a genuinely affordable option to buying your own home, and an increasing number of young Londoners are going down this route. Rather than paying £8,000 in rent each year to a landlord and not seeing any return, Dave would be able to pay the cost of his boat off in less than six years and have an investment that would keep its value at the end.

But what about the mooring costs? There are two types of moorings arrangements. A fixed mooring will guarantee you a permanent spot in a prime part of London, with water and electricity on tap. But, not only are these very difficult to get your hands on, they will set you back many thousands of pounds a year. Not very Lowe Cost Living.

Alternatively, the affordable option is to go for a roaming mooring, which entitles you to stay in one spot along the canal for a maximum of two weeks before having to move a minimum of 500m in either direction along the canal or pay a fine. This is controlled by the Canal and River Trust and ensures that the waterways are kept relatively unclogged. If you are prepared to be a bit more hands-on, this allows you to stay in some of the finest spots in London for less than the cost of council tax on a house for a year.

As part of my rent, which set me back £350 for the month, I had agreed to help with the renovation of his boat. Truth be told, I didn’t really have a choice; it was a building site, littered with materials, tools and boxes.

Creating my own room

Task number one was to create my own room at the bow of the boat. A couple of late evenings later we had managed to put in some partitioning and, after much trial and ?error, two fully functioning doors. I slept on a futon and used the wood burner that had yet to be fitted as my wardrobe. It was spacious, quiet and somewhat homely.

Bathroom facilities were basic to say the least. While Dave had planned to fit a standard bathroom in the long term, it wasn’t deemed a necessity in the short term, so we made do with a chemical loo that had to be manually emptied once a week.

Without any partitioning we got creative and piled up a selection of boxes to give each other some privacy. However, we did make a house rule ?that if ever we had female guests, we both had to exit onto the main deck.

With running water yet to be installed, shower time consisted of mixing a kettle full of hot water with cold water we had collected from one of the water points along the canal. Sitting in an empty bathtub, which had yet to be plumbed in, you only had one bucket to undertake your ablutions. Once finished, it became a real team effort between us to empty the bath with a selection of buckets to help. I must admit to having a slight sense of humour failure when Dave broke the cord on the generator, our main source of power, therefore knocking out the kettle and leaving me to have cold bucket showers by candlelight. At that point, canal living was not such an idyllic existence.

But the positives did outweigh the negatives, however, and it was tough to pick a particular highlight. Cycling along one of the most colourful stretches of canal to work each morning, arriving back after a long day in the office to go for a sunset cruise down to the pub and back, getting to grips with the locks, being invited by other boaters onto their vessels for dinner were all contenders.

What I did get from my time was a sense of community with those living on the waterways, something which seems increasingly lacking in the rest of London life. But before I get ahead of myself I would stress I am yet to do a winter on the canal, which, I understand, can be tough going.

Next up I will be staying in the wonderfully named Y-Cube, a flat-pack home developed by the YMCA that has been earmarked as a serious contender for providing affordable living in London. I am also moving west to spend some time as a security care-taker for a disused halfway house in Hammersmith for less than £100 pcm.

Stay posted @lowecostliving.

Convenience at an affordable price: inside the private rented sector

Demand for convenient locations with lower costs drives the private rented market for young professionals in the capital.

Size and high-specification finishes are not a high priority for individuals looking for schemes in highly desirable areas in central London for a reasonable amount. Location and therefore convenience are of primary importance for young professionals.

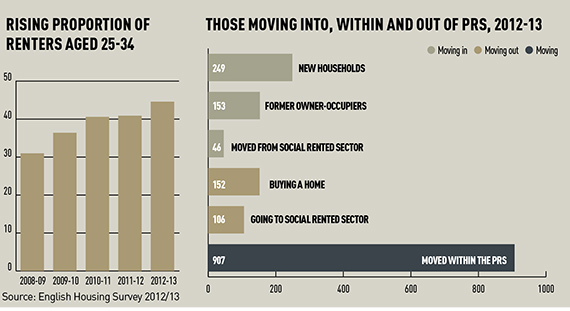

Young graduate workers are quick to be labelled “generation rent” as the costs of being a tenant in the private rented sector increase – and the primary reason behind rises in rent is a shortage of suitable properties.

In order to meet the rising demand from this market, 49,000 new homes per year are needed – but at present only half of those are being built.

The PRS accounts for 26% of all London households and, critically, is the only tenure in London that is growing as others decline.

In addition to rental increases resulting from lack of supply, young professionals are further being squeezed by inflation. This additional upward pressure on cost, coupled with stagnation in earnings, is why renting feels a lot more expensive.

In some cases, young professionals are spending more than 50% of their monthly salary on rent.

These market trends add to the growing appeal of bespoke HMO accommodation, which focuses on small-bedroom units with an element of communal living and typically features rents that are 50% lower than the area might normally expect to achieve.

Lucy Jones is head of investment lettings at Knight Frank