In this second part of his series on historic architecture, Paul Collins continues his overview of styles and periods, surveying the years between 1714 and 1939 – from the beginning of the Georgian period until the start of the Second World War.

Architectural time periods

- Georgian covers the reigns of George I to George IV (1714-1830), including the Regency (1811-1820)

- William IV 1830-1837

- Victorian 1837-1901

- Edwardian 1901-1910 (but often taken to include up to 1914 and the beginning of the First World War)

- Interwar 1918-1939

As noted in the first part of this series, covering the Norman to Stuart period, the ability to identify, describe and evaluate historic buildings is a key skill for many property reports. This holds true whether for sale, letting, building survey or development-related purposes. This ability takes time, but keen observation and lots of desktop research will of course help. It is hoped that the following brief exploration will help signpost that journey.

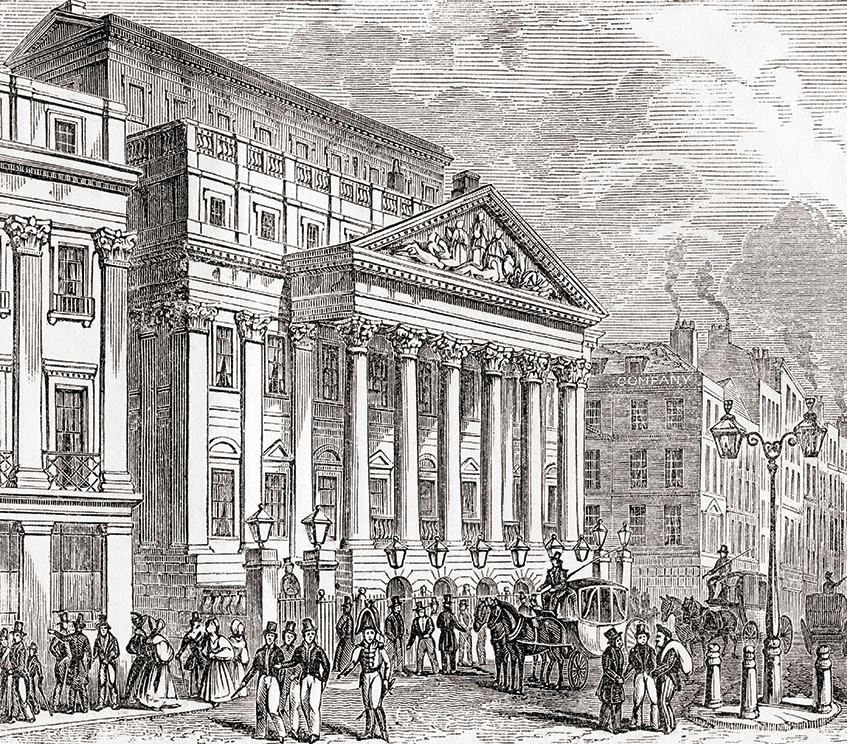

Georgian and Regency: 1714–1830

This long period produced some of England’s finest building work.

The early part of the era saw a return from a 17th-century flirtation with the more extravagant Baroque to the balanced and controlled Classicism of the Palladian School (drawn from the work of 16th-century Italian architect Andrea Palladio).

The early years saw the first astylar (without columns) terraces in Burlington Street, London. On larger detached houses and some later terraces, the style also saw the ground floor treated as a “basement” or plinth (often rusticated) on which the main emphasis was given to the first floor, where the principal rooms were located. The windows of this floor were given greater height when compared with windows on the upper floors. This approach is known as “piano nobile” (from the Italian for “noble floor”).

Towards the end of the century, reaction set in against the more controlled trend of the Palladians. Many architects turned towards a more relaxed and romantic approach to Classicism, coupled with a growing interest in other historic and foreign styles. However, while facades may have varied, with different style influences, the overall form of the terrace remained constant.

Following the influence of Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill in Twickenham, from the middle of the 18th century Gothick (with a k) became a fashionable way of ornamenting the exterior of a Classical shell. Castellated parapets, lancet windows and gothick tracery in windows were all typical. Castle Ward in County Down has one Classical facade and the other gothick.

Mainstream middle-class domestic buildings in the classical style displayed the following features: classical columns on door surrounds, fanlights over doors, Flemish bond brickwork, string courses between different floors, quoins on building corners, and gauged (flat) arches made from “rubbers” (soft bricks).

During the later Georgian and Regency period, bow windows were introduced, as was the use of curves in the design of complete terraces of houses. Bath’s Royal Crescent is a great example of this, as is the Crescent in Buxton and many parts of Edinburgh New Town.

“Bordered” sash windows were also introduced with the greater availability of large panes of glass, glazing bars becoming much thinner.

The frames were also strengthened by the use of a “horn” in the bottom corner of the window. Ironwork was increasingly popular for verandas and for balconies.

William IV: 1830-1837

The predominant style remained very much in the manner of the late Georgian and Regency period.

Victorian: 1837–1901

Queen Victoria’s lengthy reign covered a number of evolving architectural styles.

Classical, Gothic and other revivals

This period saw the continued use of classically based styles, but, at the same time, the more serious and learned revival of Gothic (no k) was popularised, in particular by John Ruskin through his book The Seven Lamps of Architecture and the work and writings of Augustus Pugin. Pugin’s book, Contrasts, written in 1836, was particularly influential in comparing and contrasting buildings of medieval England with their 19th-century counterparts. Along with many churches and institutional buildings, Pugin ended up co-designing the Houses of Parliament with Charles Barry.

Victorian Gothic included the whole range of styles and ornament from the early English, decorated and perpendicular periods, all suitably reinterpreted to suit contemporary domestic and commercial whims and fancies. Pointed arches, 45-degree and 60-degree roof pitches, turrets, oriel windows, drip labels, crockets and finials were all typical. Additional features such as decorated bargeboards and red, white and black brickwork also became popular (sometimes referred to as Venetian Gothic). English bond brickwork also became as common as Flemish bond, especially on commercial and industrial buildings.

The long-established passion for Classical by some parties, as compared with the Gothic school, led to heated debates, so much so that the conflict has been referred to as the “Battle of the Styles”.

Apart from this, the century also saw revivals of Romanesque, Byzantine, Tudor, Elizabethan, Jacobean and Baroque styles.

In addition, many architects and builders freely drew from and combined the characteristics of many styles and periods. This approach is known as “eclecticism”.

The mid-19th century saw the first large-scale development of the “suburbs”, again with a mix of Italianate and Gothic styles. Towards the end of the century, the so-called Queen Anne style was “invented”. The style was less a copy of original Queen Anne, and more a delightful blend and update of various features of the period.

Arts and Crafts

Something of an alternative to revival styles was the “Arts and Crafts” movement that developed from the 1860s. Strongly promoted by social reformer and designer William Morris, the style hinged on the “rediscovery” of vernacular (local and traditional) techniques, styles and materials. In the disposition of plans and room uses, form followed function rather than following the dictates of symmetrical balance. Some of the more commonly associated characteristics include: timber framing, hanging tiles, weather boarding, small mullioned windows, buttressed walls, generously sized front doors and water butts. These features were subject to four basic principles:

- be truthful to structure and materials;

- the use of natural, local materials;

- simplicity; and

- quality craftsmanship.

Art Nouveau

The Art Nouveau movement at the close of the century was essentially a decorative approach, but was important in that it was almost the first attempt at producing a new aesthetic since medieval Gothic. It is typified by the use of sinewy and sensuous flowing lines. One architect at the time critically described its characteristic feature as “the squirm”.

National building Acts and working-class housing

It was not until the Public Health Act of 1875 that the first effective controls were introduced to moderate the quality and layout of new working-class houses. The simple “two-up two-down” terraced house that fronts directly on to the street with a long thin backyard is typical of the late 19th and early 20th century – as typified by Coronation Street-type housing (though, of course, that’s a TV set).

Edwardian 1901–1910 (1918)

This last period before the real beginnings of the Modern movement was often characterised in commercial and public buildings by a revived, highly sculptured Baroque style. This seemed to fit the “pomp and circumstance” of the British Empire.

In lay terms, the style and appearance could be described as “wedding cake” architecture, like one of Liverpool’s Three Graces – the Port of Liverpool Building (built between 1903 and 1907).

The early 18th century Queen Anne style, as well as all other Classical and Gothic styles, also continued to flourish.

While the time period of Edwardian architecture was relatively small, the period saw an enormous boom in population and, in turn, development. Many of the first “garden suburbs” were built during this period. Their architectural and urban design style was also very much in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Interwar: 1918–1939

This period is characterised by three major design and development themes:

(i) the birth of the Modern movement;

(ii) the invention of Art Deco; and

(iii) the increased growth of the suburbs in various Arts and Crafts and “Tudorbethan” derivatives.

The roots of the so-called Modern movement can be traced in part to both the Arts and Crafts movement (form follows function) and the new engineering capabilities of iron and steel form structures (and the invention of the lift).

In interwar continental Europe, the work of Le Corbusier in France and architects and designers of the German Bauhaus led much of the new philosophy and approach.

Le Corbusier is remembered for his sleek, minimalist villas. Simple lines with an emphasis on the horizontal and unfussy facades were characteristics. He used steel frames to allow free-form space to be created inside the external non-load-bearing facades. Le Corbusier built nothing in the UK, but his influence on the design of post-Second World War local authority flats was very strong.

The work of the Bauhaus “school” from the 1920s covered not only architecture but industrial design, furniture and other everyday objects. The basic philosophy was in creating design that should be functional as well aesthetically attractive – and not unnecessarily adorned with ornament. The school was closed by the Nazis in 1933, at which point most designers left for the United States and Britain to make their mark.

Another Modernist émigré architect – not from Nazi Germany, but Georgia – was Berthold Lubetkin. He and his practice, Tecton, had many modernist commissions, but if there is one building that epitomised the best of 1930s flats, it is Highpoint in London, N6. The superb, now Grade I listed, seven and eight-storey, white-finished concrete building looks almost as if it has been designed this year.

Alongside the more minimalist Modernist style was Art Deco. This more decorative style is characterised by the use of “jazzy” and other historic motifs in a modern idiom, as opposed to the purity of form depicted by the mainstream Modern movement. It was essentially a decorative system rather than one that had any structural elements. Probably one of the most well-known examples is the Chrysler Building in New York with its stainless steel spire. In the UK, purpose-built cinemas were very often built with an Art Deco frontage. The style, also associated with a streamlined look, also featured in many pubs and sometimes other public or commercial buildings.

Paul Collins is a senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University and Mainly for Students editor

Next time: a brief exploration of post-war architecture, a review of listing and conservation matters and what might/should make for good design.