Paul Collins continues his three-part overview of the development process.

The first part of this series examined site search and land acquisition. This second part looks at the process of gaining planning permission. In doing so it considers: pre-application discussions, planning applications, design and access statements, planning agreements, planning decisions, appeals and listed building consents. It should be noted however (as discussed in part 1) that some landowners and developers may seek planning approval before sites are purchased.

For example, a developer may only proceed with an acquisition subject to a suitable planning consent.

Finally, it is important to understand that, apart from granting permission to build, a consent will often release the site’s development value and, in so doing, provide the basis for securing finance and confidence to market a scheme if it is for eventual sale or letting.

Development management

Development management (or development control as it was once referred to) is the process by which a planning application is made and considered.

For a developer, to gain a planning approval is an early and crucial step in the development process for a project.

Planning permission across the UK is generally required where development constitutes the building, engineering, mining or other operations in, on, over or under land.

From a local council perspective, it is the council’s duty to consider the validity of all planning applications with regards to:

- the policies of an approved local plan;

- national policies, including those of the devolved nations; and

- any other “material considerations”.

The term “material considerations” is important. In practical terms, it means that other matters not necessarily covered by the formal policy can also be considered in determining an application.

Examples might include: overlooking/loss of privacy, loss of daylight/sunlight or overshadowing; scale and dominance; layout and density of buildings; appearance/design and materials proposed; access and highway safety; and noise, dust, fumes, etc.

They do not include things like possible reductions in property values, boundary disputes or loss of views.

Planning applications: outline and full

The nature and extent of the planning application process will vary from scheme to scheme.

The size and complexity of a scheme will be an important variable, as will the ability of individual planning authorities to give time, care and resources to consider and process an application.

Planning applications can be made on an outline or full basis. An outline application is intended to get permission in principle for the use and key access issues.

Applicants cannot start development on the grant of such an approval. Full applications have to be made in order for that to happen.

The advantage of an outline application is that developers will have confidence that their proposals are going in the right direction.

Applicants may consider it helpful to have a pre-application discussion with a planning officer, although this is subject to a fee.

Advice concerning small domestic applications can cost £50-£60, whereas, for large and complex schemes, it may run to thousands of pounds.

If chosen, as much information should be shared as possible, as well as advice sought as to constraints and ways to improve compliance with planning policies and any other material considerations. In making a planning application, a fee is charged.

Small individual householder applications can cost circa £200, whereas big, complex schemes, again, can amount to many thousands.

Design and access statements

While sometimes seen as a costly burden, a DAS can provide benefits to both an applicant and the local authority. This is because its purpose is to explain and justify the thinking underpinning the design proposals.

Although now archived, the Commission for Architecture in the Built Environment advice still provides a helpful guide to their character and purpose.

In supplementing the information contained in a planning application, a DAS explains how the design characteristics of the scheme have rigorously addressed the following:

- Land uses and amounts: what buildings and spaces will be used for and floor areas;

- Scale: the size and massing of buildings and spaces in relation to the site and its context;

- Layout: the arrangement of buildings and spaces on the site, and the relationship between them and what is next to the site;

- Landscaping: how spaces work and enhance and protect the character of the site and area;

- Appearance: the aesthetic quality and proposed materials of buildings and spaces;

- Vehicular and transport links: the character of and rationale for access points and routes and how the site responds to road layouts, active travel, and public transport;

- Inclusive access: how everyone gets to and moves through the place on equal terms, regardless of age, disability, ethnicity, or social grouping.

Design reviews

For large or potentially contentious schemes, a local authority may also suggest a design review.

Design reviews are carried out by groups of third-party design and development professionals who scrutinise draft proposals and make constructive comments before a scheme goes forward with a formal application.

For further information see: www.designcouncil.org.uk/resources/guide/design-review-principles-and-practice .

Planning agreements

In addition to preparing and submitting a planning application, developers may also have to enter in to a planning agreement under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990.

Such agreements are typically used to secure (private sector) funding to assist making a proposed development acceptable from a planning policy point of view.

This might include a developer making financial contributions to off-site road and traffic measures, or the inclusion of a given percentage of affordable houses as part of an overall residential scheme.

The cost of such agreements can be quite expensive.

A planning agreement is negotiated and agreed before a planning application is determined and is considered alongside an application as a material consideration.

Please note, in England and Wales these contributions may be in addition to a locally based community infrastructure levy. CIL is a local tax to support new infrastructure generally and is based on a published charging schedule for different types of development.

See: www.gov.uk/guidance/community-infrastructure-levy.

Both section 106 and/or CIL payments are costs that must be taken account of in a development appraisal.

However, while borne by the developer, they should at the same time improve the marketability of a scheme.

For large-scale residential development, local authorities might seek financial contributions for the building of additional classrooms at a junior school. Prospective buyers with young families, for example, will almost certainly want to be assured about their children being able to get into the local school, rather than further afield.

The other devolved regions of the UK have similar planning agreement powers, but Scotland and Northern Ireland do not have CIL.

Decision making

The choice of whether the planning case officer or planning committee makes the final decision will depend on what level of delegation has been given to officers.

In practice, most non-controversial small domestic type applications are delegated, while others go to committee.

All applications that go to committee will have a formal recommendation on whether to approve, approve with conditions, or refuse. It is then up to the planning committee to decide.

It is normal practice to follow the recommendation of the case officer. In doing so, the case officer will draw together all policy, consultee and third-party stakeholder views in coming to their recommendation.

Not doing so can provide grounds for a potential appeal, if there are not sound planning grounds for not doing so.

All planning decisions must have regard to the local development plan, national policies and any other material considerations.

Planning appeals

Should a planning application be refused or granted with conditions not to the liking of the applicant, there is an opportunity to appeal.

Appeals may also be made if decisions are not made within the prescribed or agreed time.

The appeal is not made to the local authority but to central government ministers in England, in Scotland and Wales to the respective devolved governments, but in Northern Ireland to an independent Planning Appeals Commission.

There are strict time limits by which to submit an appeal after a determination and they vary with the complexity/scale of a scheme.

Details on this can be found at www.gov.uk/government/publications/planning-appeals-procedural-guide/procedural-guide-planning-appeals-england and www.gov.scot/publications/planning-permission-appeals-form-guidance.

Planning appeals, while sent to the secretary of state in England, are normally decided by the Planning Inspectorate, unless particularly controversial. The Planning Inspectorate is a group of planning professionals who read and listen to the evidence and then issue a decision.

Applicants can ask for their appeal to be held by:

- Public inquiry This would normally only be used for major applications, as it can be time consuming, procedurally legalistic and expensive – and when planning consultants think there will be a reasonable chance of winning.

- Written representations Cheaper and quicker than a public inquiry and more usually used for straightforward cases where any form of cross-examination of evidence is thought to have little value.

- Informal inquiry The third option has the advantage of simply getting around a table without the formalities of a public inquiry with the aim of reaching a mutually satisfactory outcome.

The timescales between the three methods varies considerably, with a public inquiry taking the longest time (and being the most expensive to all parties).

The outcome of such decision can only be appealed again to the High Court on a matter of law – not a re-examination of the planning merits of a case.

The case for and processes involved are broadly similar across the UK and may include: not properly taking into account national laws, national and local plan policies and/or other material considerations; and/or not properly following the right statutory procedures.

Pursuing this route can be lengthy and expensive.

Listed building consents

Finally, it should not be forgotten that many buildings of historical and/or architectural significance across the UK are protected in some way from demolition or inappropriate change without additional consideration and approval.

These kinds of buildings and structures are protected by virtue of being “listed” or located within a designated “conservation area”.

As result, any proposed alterations, demolition or extensions must gain a planning consent, but this in itself does not give a developer the freedom to start construction work.

Listed building consent is required as well. This can cover the outside, inside or, more usually, the whole of a building.

However, as for planning applications, there is a right of appeal which is broadly similar in process and often considered at the same time.

Final thoughts

Planning is a crucial and necessary part of all development projects. Nothing happens unless planning – and, where necessary, listed building – consent is given.

It can be and often is expensive and burdensome, but its aim, in part, is to help developers produce schemes which are sustainable and attractive.

Planning has tried to move away from being reactive and critical, to positive and supportive, with a high emphasis on encouraging good design.

Indeed, the government is currently pressing for much new development to be “beautiful”, however subjective that definition may be.

Current challenges in relation to planning

- Not all local plans are up to date

- There is an acknowledged lack of local authority planning staff, which is delaying getting advice as well as decision making

- In England, the government is progressing a Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill which will have impacts on the development process, including a proposal to replace CIL with a new infrastructure levy

- In Scotland, a new national planning framework was published in February 2023 n The new Planning Portal in Northern Ireland has been criticised as not fit for purpose by practitioners

Rookie errors

- Not filling in the planning application form properly and comprehensively

- Mixing up imperial and metric measurements

- Not attaching all relevant location maps and site plans to an identifiable scale and north sign with the site area outlined in red

- Not properly calculating the appropriate fee

- Forgetting planning approval does not mean you can build unless you also have building control consent

- Not taking advantage of pre-application discussions with planners

- Not talking to neighbours, statutory undertakers and other stakeholders before you apply for permission

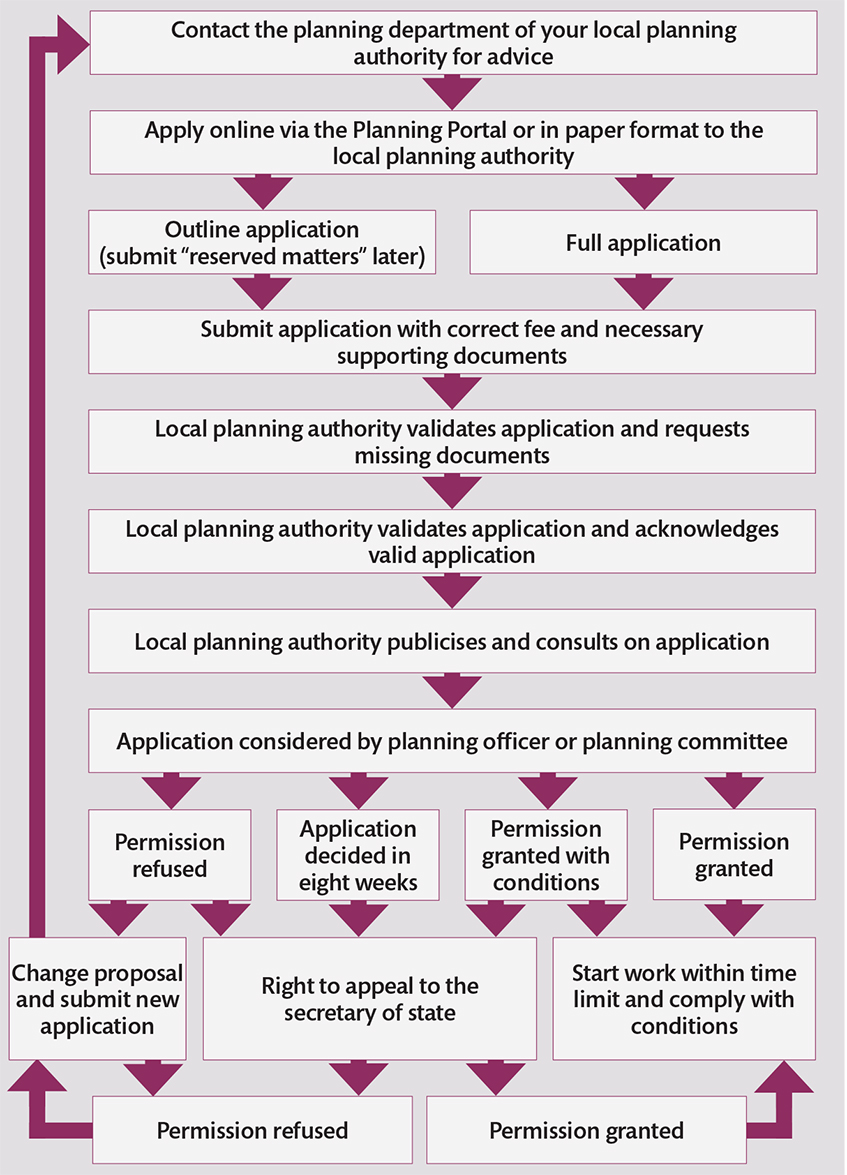

The process

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing, Communities and Local Government sets out the stages in England, which are broadly similar for elsewhere in the UK:

Source : www.planningportal.co.uk/planning/planning-applications/the-decision-making-process/introduction

Most local authorities also provide lots of information on current applications, including ways to comment on applications – those decided and being appealed. For example, click here.

Further reading

Government guidance on planning applications across the UK can be found at:

- England – www.planningportal.co.uk

- Scotland – www.eplanning.scot/ePlanningClient and www.gov.scot/publications/guide-planning-system-scotland

- Wales – www.planningportal.co.uk/wales

- Northern Ireland – www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/making-planning-application

Paul Collins is the editor of Mainly for Students and teaches at Nottingham Trent University

The third and final part of the series will provide an overview of building control approval, construction procurement, marketing, handover and post-occupancy evaluation