Over the course of the last century the world’s urban population has grown 15-fold. That is a tough multiplication to imagine in real terms. But, put simply, 200m people lived in urban areas in the early 1900s. Today that figure stands at around 3.6bn – just over half the world’s total population.

And the influx into global cities will not stop there. The United Nations predicts that 64% of the developing world and 86% of the developed world will be urbanised by 2050. Nearly 90% of the increase will be concentrated in Asia and Africa.

On the one hand, this mass migration to urban areas, coupled with a natural increase in global population, presents a wealth of opportunity. Not just for the development of cities and the people living in them, but also for the real estate sector. Growing populations need places to live, work, learn, heal and play. Demand for property and infrastructure in all corners of the market will naturally increase alongside expanding populations all over the world.

But meeting the needs of this burgeoning urban population will not come cheap. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that governments will have to spend around $71tn by 2030 in order to provide adequate global infrastructure for electricity, road and rail transport, telecommunications and water to keep up with predicted rates of urbanisation. But what happens if we cannot deliver what is required in time to meet such growing demand?

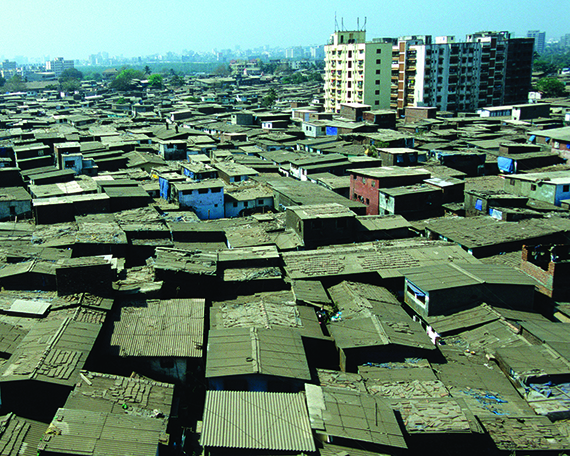

When vast swathes of people gravitate towards areas of economic opportunity faster than adequate housing and infrastructure can be put in place to cope, informal settlements spring up. And therein lies a whole new debate. Dubbed slums, favelas, barrios or shanty towns, depending where they are in the world, the perception of these densely populated neighbourhoods is that they are the epitome of squalor – devoid of the necessities for basic living conditions. But is intervention the answer?

Efforts to manage today’s rapid sprawl of informal settlements are myriad but are governments and urban planners actually in danger of interfering too early? Is there a risk of knocking the natural development of these potential future cities off kilter by trying to fast-track them into a westernised urban ideal?

Organic development

Historically, cities have been allowed to sprawl largely uninterrupted. London once comprised houses made of wood, mud and dung, and the practice of throwing human waste into the streets was commonplace. Now it is a thriving, cosmopolitan metropolis and one of the world’s leading economic powerhouses.

The process of installing and improving its infrastructure and public services has taken hundreds of years but the foundation on which London is built – the organic network of streets connecting the city – is still clear to see. And evidence suggests that these foundations stem from human instinct, with informal settlements across the world being built on the same principles.

These areas will almost always feature a network of streets, some of which will be major thoroughfares and others smaller offshoots.

Yolande Barnes, head of research at Savills, explains that virtually every house built by its occupants will feature the same two-storey model: a semi-public space on to the street, from which to do business and interact with the public; a communal family space at the back of the ground floor; and a completely private sleeping space upstairs.

“Human beings, left to their own devices and regardless of which continent they’re on, will build similar houses and streets,” she says.

“It means that anyone landing in, say, the Dharavi slum in Mumbai or one of the favelas in Rio or somewhere in Asia will recognise what’s going on.”

Dharavi is perhaps one of the world’s most famous slums. Founded in 1882, it has since grown to cover 536 acres and is home to a population estimated to be between 700,000 and 1m.

As in so many informal settlements there is no doubt that there are major sanitation issues to contend with. Access to utilities is sparse and often illegal, residents frequently resort to relieving themselves in a nearby river that is also a source of drinking water, and the spread of disease is rife. On top of all of this, the fragile construction of homes in these areas makes them particularly vulnerable to natural disasters.

And yet still there have been questions raised over whether major intervention at government level or wide scale redevelopment is the answer. Not least because this is not necessarily what the residents even want.

Among India’s efforts to eradicate slum housing has been the offer of new and free apartments on the edge of the city. But it is an approach that has failed to gather momentum in Dharavi after being met by criticism from slum residents.

Because, despite the many downsides to daily life in Dharavi, it has an active informal economy estimated to be valued at more than $500m. This is made up of household enterprises that produce goods including leather, textiles and pottery products that are then exported around the world. And rather than move, many residents would prefer to stay put so they can remain in the hub of economic and social activity.

“Whenever you try to relocate these dwellers of informal settlements they always go back to the slums because they are such productive places,” says Barnes. “It must be hugely unpleasant [to live there] but that is outweighed by the economic advantages. People can’t live in the fullest sense in homogeneous housing estates. The only reason we do so in the western world is because we have cars. It seems to me that we should concentrate instead on alleviating poverty and providing sanitation.”

“Forget about building new housing on the edge of the city and giving slum dwellers title to those empty flats instead of the land they occupy now, where their families and livelihoods are,” adds urbanist Greg Lindsay.

“Why don’t we give them title to their land instead, and then develop new models for helping them build their shacks into homes?”

He points out that this is how cities, including many of Brazil’s favelas, have always evolved.

“It’s just not happening fast enough for developers, so something has to change,” he adds.

But what and, crucially, who should take responsibility for the next steps?

Restrained intervention

This is where the argument for government and/or developer intervention on a lesser scale comes in.

Because while there are strong arguments against razing informal settlements to the ground, recognising the distinct difference in circumstances between today’s urban population explosion and the historic growth of major developed cities to date is crucial.

That difference is in scale. In 1801, when the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, London’s population was just over 1m. But what we are facing now is on a much larger scale. Neza-Chalco-Itza, one of Mexico City’s many barrios, and the largest slum in the world, is home to roughly 4m people, about 10% of the wider city’s population.

And there are myriad other examples. Can the unprecedented urban population boom of Nigeria’s former capital city Lagos, for instance, really be compared to the relatively slow burn of somewhere like Paris? The French capital’s metropolitan population of 12.3m grew from 8.4m over a relatively leisurely 40-year period, while the Lagos state government estimates its own metropolitan population to be 17.5m and growing at a rate of 500,000 a year.

As such, is it naïve to assume that the favelas of Brazil or the shanty towns of South Africa can develop successfully if left entirely to their own devices?

Even if a radical displacement approach is not the answer, there are alternatives, such as improving the basic infrastructure of informal settlements.

Cable car systems are being introduced at Rio’s various favelas where access through the narrow alleys and staircases of the sprawling settlements can be a two-hour trudge on foot. The benefits are clear as a result of these rapid transit systems, which enable commuters to cross the favelas in as little as 16 minutes and give residents easy access to possible job opportunities outside the boundaries of the settlement.

Employers set to benefit from the arrival of job-hungry people can also shoulder some of the responsibility of managing their accommodation needs, says Tim Pugh, planning partner at law firm BLP. “People migrate to urban areas because there are jobs to be had with better pay,” he says. “There is an economic impetus on the part of industrialists to provide worker accommodation for migrants from rural areas,” he says. “As China’s economy continues to expand and the expectations of its working population rise, there is an increasing focus on planning settlements holistically from the start.”

Projects such as interdisciplinary design practice Urban Think Tank’s Empower Shack also have the potential to help. The affordable housing solution being piloted in Khayelitsha, an informal settlement in Cape Town, features corrugated tin roofs with solar panels and essentially provides a means to electrify some of these slums.

The creation of one such solution leads to another set of questions. Who will mass replicate it? How do you build the delivery service model? According to Lindsay, it is a huge, albeit risky, opportunity and one of many that perhaps the property world could support.

Pugh agrees: “[Real estate businesses] can promote and deliver sustainable urbanisation, and insist others do so too. The bigger the investor, the more it can influence. CSR policies and sustainable investment criteria can, and do, play a role, especially with multilateral banks and mobile global capital.”

March of progress

Ultimately, the choice between allowing the organic development of fast-urbanising areas and orchestrating their progression through outside intervention is by no means clear cut. There is no one-size-fits-all approach and the likelihood is that for each slum there will need to be a mixture of the two.

There is a strong case against intervening to the point where natural urbanisation is stopped in its tracks. Apart from anything else, informal, and indeed formal settlements the world over, demonstrate that it would be impossible. The bigger question for cities and the real estate industry is whether energies can be channelled into a different model, one focused on support rather than displacement.

Competition launch: Are you the Next Big Thing?

There are hundreds, if not thousands of shanty towns, slums, townships, barrios and favelas around the world that house millions of people.

There are hundreds, if not thousands of shanty towns, slums, townships, barrios and favelas around the world that house millions of people.

These towns have their own, often successful, economies valued at billions of dollars. But they are also rife with disease, poor sanitation and crime.

Pulling them down does not solve any problems, and rehomed residents often return to reap the economic benefits. So what can be done to turn these mass urban settlements into legitimate, sanitary and productive new towns?

The challenge is yours.

After attempting to solve the problem of global over-population in 2015, Estates Gazette, with partner Cluttons, has set a new challenge – finding an alternative solution to demolition for the growing number of slums around the world.

The Next Big Thing competition is for anybody who has an idea to help solve this very real issue, with the winner to be announced at the 2016 EG Awards.

You can be as creative and forward thinking as you like, but the global panel of judges will be looking for proposals that are viable as well as innovative and impactful.

This worldwide competition is open to individuals from across the industry at any level. You could be a student with a proposal you weren’t sure how to pitch, a chief executive with a burning desire to solve a real human problem or someone already working on plans to improve but not destroy the makeshift urban settlements that are growing around the world.

Visit www.thenextbigthingcompetition.com to find out how to enter.

To send feedback, e-mail Janie.Stamford@estatesgazette.com or tweet @JanieStamford or @estatesgazette